2020 olive harvest season: low yield amidst access restrictions and settler violence

The 2020 olive harvest season, which took place in October and November, was an exceptionally poor one in terms of oil yield. The Palestinian Ministry of Agriculture expects a total of 13,000 tons of olive oil (including some 1,500 tons in the Gaza Strip), which represents a more than 55 per cent decrease compared with 2019. This has been attributed to the alternate fruit-bearing “on and off seasons”, coupled with poor rainfall distribution and temperature extremes during the growing cycle.

This season was also characterized by the difficulties that farmers faced in obtaining Israeli authorization to access their land in restricted areas behind the Barrier and near Israeli settlements. This was due to the Palestinian Authority’s (PA) decision, in May 2020, to suspend coordination with the Israeli authorities, following Israel’s announcement of its intention to annex parts of the West Bank.[1]

However, following the Israeli authorities’ easing of some procedures, most farmers who in previous years had been authorized to access their land in the restricted areas, were able to do so this year too, despite the lack of PA coordination. The restrictive access regime applied in these areas throughout the year, which impedes essential agricultural activities, has continued to impact on olive productivity and value.

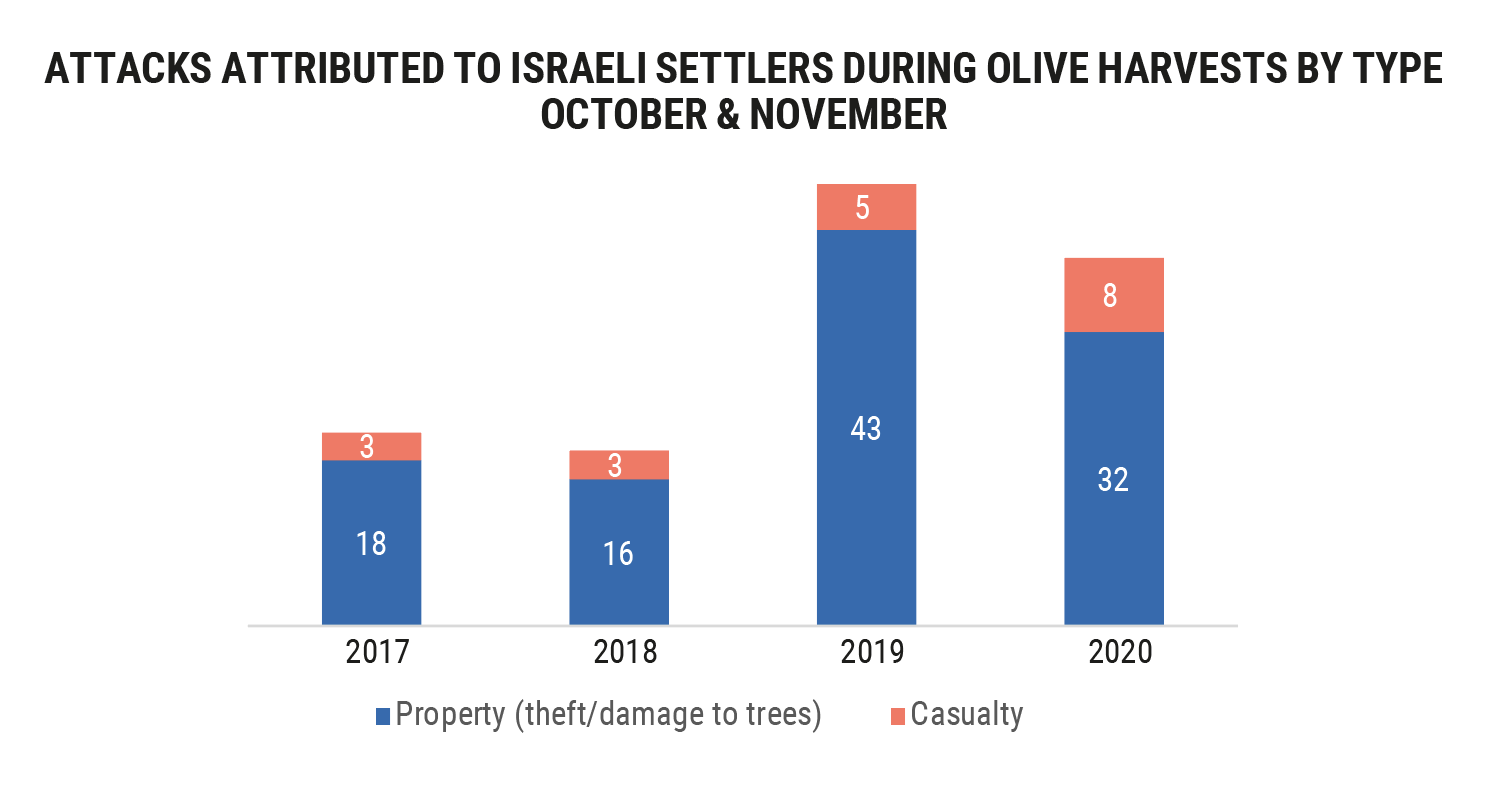

As in previous years, this harvest season was also disrupted by Israeli settlers, who physically assaulted farmers, vandalized or set fire to their trees, or harvested and stole their produce. Although the absolute number of such incidents has slightly declined compared with 2019, this is most probably linked to the limited presence of farmers in the field due to the poor season.

The olive harvest is a key economic, social and cultural event for Palestinians.[2] As the occupying power, Israel must ensure that Palestinians are able to participate in, and fully benefit from, this activity. This includes ensuring that farmers can access their olive groves throughout the year, and that their trees and agricultural property are protected from damage and theft.

The Israeli authorities’ recent efforts to facilitate the access of farmers to restricted areas, as well as the deployment of additional Israeli forces to prevent settler attacks against harvesters, are positive and welcome steps. However, longstanding access restrictions imposed in connection to settlements and the sections of the Barrier running inside the West Bank, including in East Jerusalem, established in contravention to international law, continue to undermine agricultural livelihoods. Additionally, the enhanced presence of Israeli forces in some areas and at certain times has been largely ineffective in preventing large-scale vandalism to olive trees. Longstanding gaps in the enforcement of the rule of law on violent settlers remains of major concern.[3]

The International Court of Justice Advisory Opinion

In 2004, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued an Advisory Opinion on the “Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory”. The ICJ stated that the sections of the Barrier route which run inside the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, together with the associated gate and permit regime, violated Israel’s obligations under international law. The ICJ called on Israel to cease construction of the Barrier ‘including in and around East Jerusalem’; dismantle the sections already completed; and ‘repeal or render ineffective forthwith all legislative and regulatory acts relating thereto’, referring to the gate and permit system.

Obstacles to accessing land in Barrier restricted areas

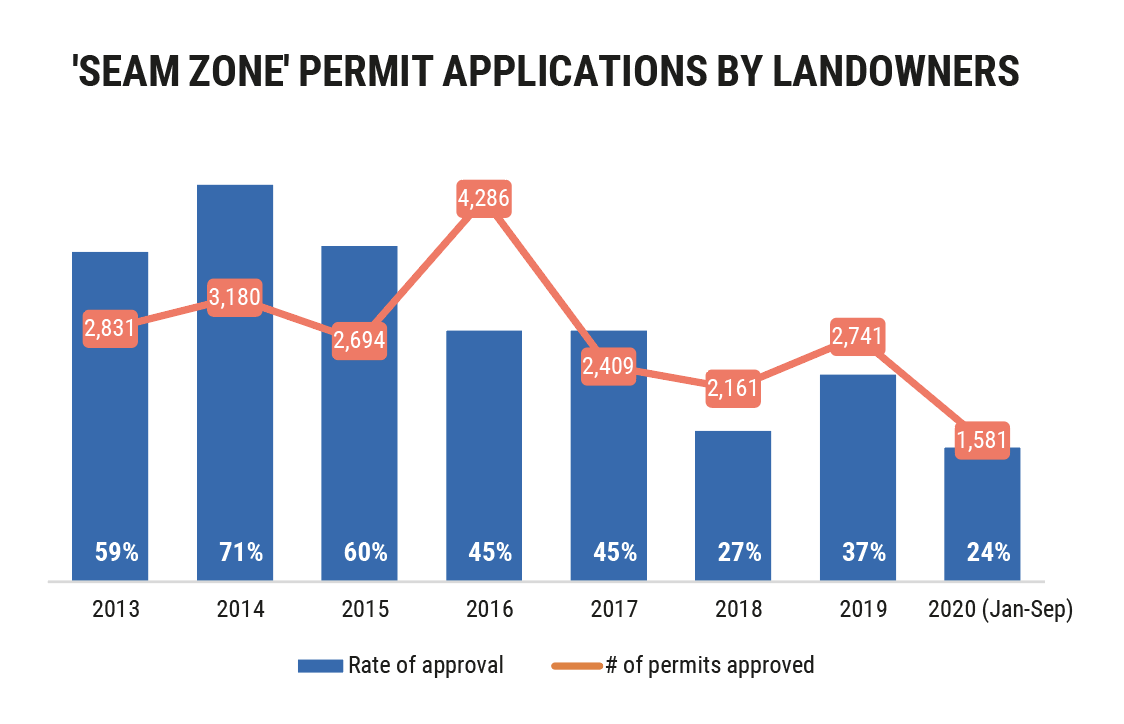

This year’s developments took place against the backdrop of a declining trend in the approval rate of permit applications by landowners, which are usually valid for two years, to access their land in restricted areas behind the Barrier, the ‘Seam Zone’.[4] According to official data, the approval rate fell from 71 per cent of applications in 2014 to 37 per cent in 2019.[5] While this rate further declined in 2020 to 24 per cent (up to 1 October), this figure may not be representative, due to the disruption of the regular application procedures, following the halt in Israeli-Palestinian coordination. According to the Israeli authorities, the multi-year decline in the approval rates is due to the large numbers of people who use their ‘Seam Zone’ permits to enter Israel illegally for work purposes.

Source: State Attorney’s response to Hamoked’s petition to the Israeli High Court of Justice (HCJ 6896/18)

By contrast, the rate of approval for short-term permits (called ‘personal needs’ permits), which entitle bearers to carry out agricultural work, stood between 2013-2020 at an average of 90 per cent. According to Israel’s official data, by 1 October 2020, 3,500 such permits had been approved, constituting nearly 92 per cent of all applications.

Following the halt in coordination, the PA did not perform its usual function of facilitating the handling of permit applications. Instead, Palestinian farmers were required to present themselves in person at their local Israeli District Coordination and Liaison Office (DCL) to submit permit applications. Given the physical conditions and arrangements at the DCLs, this led to instances of overcrowding and fears of potential COVID-19 transmission, especially in the northern West Bank, where the majority of restricted land is located.

In response to complaints by humanitarian and human rights organizations, in late October, the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA) announced that required ‘Seam Zone’ permits would be automatically re-issued to all those granted in 2019. The ICA also agreed to allow access to those areas behind the Barrier requiring verbal approval from the Israeli authorities, referred to as ‘prior coordination’ (instead of permits), based on last year’s lists of names. By means of social media, the ICA broadcast information on the designated gates (see further detail below) and opening hours. In certain cases in the Ramallah area, farmers who had not been granted permits in 2019, were provided access to their land after providing a certificate from their village councils attesting to their connection to the land.

Overall, OCHA’s field monitoring indicates that most farmers who obtained permits or so-called ‘prior coordination’ in 2019 were able to access the ‘Seam Zone’ again. Unfortunately, due to the fact that the Palestinian DCLs did not function as normal, it has not been possible to compile comprehensive data, as in previous years.

Partial information obtained for the Jerusalem and Ramallah governorates suggest a decline of over 60 per cent in the number of Palestinians that reached their land during the harvest compared to 2019 (600 vs 1,600 in each governorate). This decline is attributed to the lesser work required due to the low yield, as well as the unwillingness of some farmers to engage directly with the ICA. In the Hebron area, the same 525 farmers who had been approved last year were also able to gain access to their land this year, mainly through a ‘prior coordination’ arrangement.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that farmers also availed of the multiple informal openings in the Barrier, used primarily by unlicensed workers to enter Israel, to access their land in the ‘Seam Zone’.

Standing orders cancelled

New standing regulations issued by the Israeli authorities in September 2019, set a limit to the number of days that farmers can access their land in the ‘Seam Zone’ a year, based on the size of the plot and the nature of the crop cultivated. In response to a petition by HaMoked to the Israeli High Court of Justice, on 25 October 2020, the State of Israel announced, that the limited-entries permit had been planned as a pilot programme, and would be cancelled because it had “failed to achieve its goals”. According to HaMoked, “this ends the most restrictive policy imposed on Seam Zone farmers to date, a source of great hardship with threatened farming and agricultural traditions in these (‘Seam Zone’) areas.”

Slight decline in the number of Barrier Gates

If permits or so called prior coordination are granted, land in the ‘Seam Zone’ can only be accessed through designated Barrier gates, or checkpoints, that are controlled by Israeli soldiers. Most of these are only open during the olive harvest period and only for a limited amount of time on these days, prohibiting year-round access. During the 2020 olive harvest, 69 gates and four checkpoints were designated for agricultural access, compared with 73 and five, respectively, in 2019. Only 11 gates open daily; ten open for some day(s) of the week in addition to the olive season; and the majority, 48, only open during the olive season and are closed for the remainder of the year.

As in previous seasons, there were complaints by farmers about the limited opening hours and the gates not opening at, or closing before, the scheduled times, or that farm vehicles were not permitted to cross the Barrier. In the northern West Bank, concrete barriers were installed at four gates to prevent vehicles, equipment and farm animals from crossing.

The limited allocation of permits, combined with the restricted number and opening times of the Barrier gates, impedes essential year-round agricultural activities such as ploughing, pruning, fertilizing, and pest and weed management. As a result, there is an adverse impact on olive productivity, quality and value. Since 2011, OCHA has been monitoring the productivity of a representative number of farmers in the northern West Bank. This year’s data continue to show that the yield of olive trees in the area between the Barrier and the Green Line has reduced by approximately 60 per cent in comparison with equivalent trees in areas accessible all year round.[6]

Access to land on and around Israeli settlements

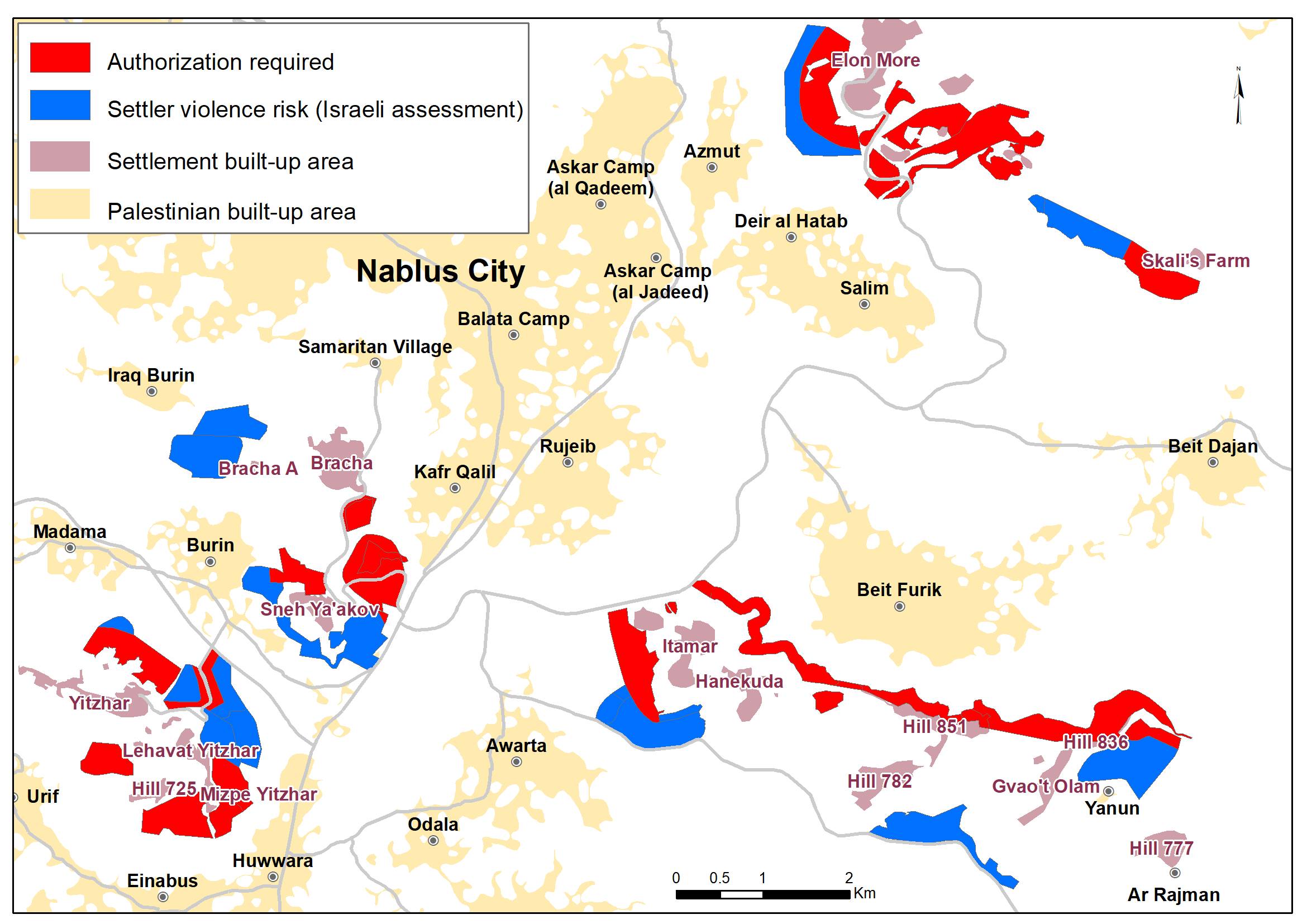

Dozens of Palestinian communities own land within, or in the vicinity of, Israeli settlements and face restrictions in accessing this land.[7] Based on the aggregation of the individual military orders and related maps issued by the authorities ahead of the 2020 season, OCHA estimated that farmers were obliged to obtain Israeli permission (or so called prior coordination) to access 13,900 dunams of land (1 dunam = 1,000 sq. metres). According to the authorities, this restriction is aimed at protecting Israeli settlers from potential Palestinian attacks. Additionally, 13,500 dunams were marked as ‘friction areas’, where Palestinian farmers are at risk of settler violence, and where “prior authorization” before accessing those areas is recommended, but is not mandatory.[8]

Based on an average of 11 olive trees per dunam,[9] it is estimated that over 300,000 olive trees are located in areas in the two restricted categories. Almost half of these areas are located in the Nablus governorate, followed by Salfit and Qalailiya with 19 and 18 per cent each, while the remainder are distributed between Ramallah, Hebron and Bethlehem governorates. There are some 110 Palestinian villages and towns located in the vicinity of the restricted and affected areas.[10]

In the past, the period allocated to farmers to harvest their olives located within, or near, settlements was negotiated between the Israeli and Palestinian DCLs. In light of this year’s suspension in coordination, the Israeli DCLs unilaterally determined the period allocated for each area and disseminated the information through various channels. Most communities were given from two to four days to access the restricted areas. During those days, Israeli forces increased their presence on the ground. Overall, access to these areas proceeded smoothly, according to the established schedule. Some communities reported that they availed of the opportunity to also plough their lands, as access earlier in the year during the ploughing season itself was blocked, mainly due to Covid-19 restrictions.

Settler Violence continues to undermine olive harvest season

During October-November 2020, OCHA documented 40 incidents of settler violence related to the olive harvest by people known, or believed to be settlers, which resulted in Palestinian injuries, damage to trees, or involved theft of produce and tools.[11] This represents a decline compared with the previous season (48 incidents); however, the 2019 olive harvest was a peak year in terms of the yield and corresponding presence of farmers on the ground, compared with this season’s record low yield, rendering comparisons difficult.

Overall, 26 Palestinians were injured during this year’s season (including 16 in clashes with Israeli forces who intervened following a settler attack); over 1,700 trees were vandalized; and Palestinians discovered that approximately 1,870 trees were already harvested by people believed to be Israeli settlers. As in previous years, the largest number of incidents was recorded in the Nablus (17) and Ramallah (10) governorates.

Of note, 40 per cent of this year’s incidents (16) took place in closed areas next to settlements where Palestinians access is restricted, as detailed above. In most of these cases, farmers found that their trees had been damaged or burnt, or that the fruit had already been harvested.

In one of the most serious incidents, on 9 October, a person believed to be an Israeli settler set fire to 600 olive trees belonging to farmers from Saffa village (Ramallah), located in the ‘Seam Zone’ next to Modi’in Illit settlement. In another incident on 12 November, after receiving the required authorization, farmers from Sa’ir village (Hebron) entered their land next to Asfar settlement and found that some 1,000 olive trees had been harvested, with some trees also damaged.

In other instances (not included in the incident count), Palestinians discovered that sewage from settlements and settlement outposts had flooded their land and caused damage to trees.

In Sabastiya village, Nablus, over 100 olives trees were destroyed by sewage from Shave Shomron settlement. Sawsan Aalwan, from Ein Yabroud (Ramallah), owns around 30 dunams of land planted with olive trees in the vicinity of Ofra settlement, which is only accessible through prior coordination: “Each year, we enter the settlement area and discover that our trees are dying from the sewage water from the settlement seeping into our land. We try to fix the problem with the limited time we are allowed to access, by diverting the sewage water away from our trees, but it’s not enough.”

“It is a shock for us when we go to our land and we see all the olive trees cut down”

Since 2013, Première Urgence Internationale (PUI) has been providing support to farmers to access their land in the ‘Seam Zone’ and in ‘prior coordination’ areas near to settlements. Additionally, since 2015, PUI has provided livelihood support to farmers, including cash assistance to hire additional workers, distributed agricultural equipment and, as a pilot project this year, electrical olive harvesters to help farmers pick their olives faster during the few days that they are granted access to their land near settlements. PUI also provides financial support to farmers affected by settler violence.

One farmer who has benefited from PUI support is Sa’id, 60 years old, from Al Mughayir village in Ramallah governorate. Sa’id owns 43 dunums of land next to the ‘Adei ‘Ad settlement outpost. Settlers from ‘Adei ‘Ad outpost are believed to have perpetrated many attacks against Palestinians and their property over the years. Although the outpost was established without Israeli official authorization, partly on privately-owned Palestinian land, it is being ‘regularized’ by the authorities.[12]

On one plot of land he owns, Sa’id planted 600 olive trees in 1982. Over the years, his land has been targeted multiple times, resulting in stolen crops, and trees cut, burned and poisoned. In 2020 alone, two attacks were recorded. In February, Sa’id’s land was bulldozed, uprooting the stems and roots of around 200 olive trees. In October, when Sa’id accessed his land on the first day of the olive harvest he found that 120 olive trees had been damaged with electric saws. Of the 600 trees originally planted, only 15 trees remain.

PUI compensated Sa’id with NIS 21,600 ($6,750), or about 80 per cent of the value of his 120 trees. He was also provided with harvesting machines so that he could harvest his trees in another plot of land in the ‘prior coordination’ area in the short time allowed to him. Once he gets access to his other plot, he will be able to plant 400 new olive saplings provided to him by PUI.

Sa’id describes the ‘prior coordination’ as a “slow death for our land” because he is only allowed to access it normally for two days in the olive harvest and one day in the ploughing season.

“Humanitarian aid is important to mitigate mine and other farmers’ losses. But what is needed now is a stronger legal response so that we get better access to our land to prevent it from being declared ‘state land’ and we will no longer be able to access it.”

[1] This coordination was renewed on 17 November, when the olive harvest was almost complete.

[2] Between 80,000 to 100,000 families rely on the olive harvest for their income, including large numbers of unskilled labourers and more than 15 per cent of working women. See: PALTRADE, The State of Palestine National Export Strategy: Olive Oil Sector Export Strategy 2014 – 2018. According to PALTRADE, the entire olive sub-sector, including olive oil, table olives, pickles and soap, is worth between $160 and $191 million in good years.

[3] According to the Israeli human rights organization Yesh Din, of 273 police investigations between 2014 and 2019 that reached a final stage, only 25, or nine per cent, led to the prosecution of offenders, while the other 248 investigations were closed without indictment. Of the latter, more than 70 per cent were closed on the grounds of ‘offender unknown’ or ‘insufficient evidence’, “indicating the police found an offense had been committed, but failed to identify the perpetrators or collect enough evidence to prosecute.” Yesh Din, Law enforcement on Israeli civilians in the West Bank, January 2020.

[4] In the northern West Bank, the land between the Barrier and the Green Line was declared closed by military order in October 2003. In January 2009, the closed area designation was extended to all, or part of, areas between the Barrier and the Green Line in the Salfit, Ramallah, Bethlehem and Hebron districts, and to various areas between the Barrier and the Israeli-defined municipal boundary of Jerusalem. According to HaMoked, the Seam Zone covers an area of over an area of 121,255 dunams, of which 70,530 dunams are private lands.

[5] The rate of approvals for permits for ‘personal needs’ in the Seam Zone, which entitles bearers to carry out agricultural work is significant higher, and stood in 2020 at around 90 per cent, 3,500 approved out of 3,822 applications.

[6] For further details on the methodology used for data collection see: OCHA Humanitarian Bulletin, February 2014, Impact of the Barrier on Agricultural Productivity in the Northern West Bank.

[7] Some of these groves are located within the fenced areas of settlements or behind the Barrier, thus requiring farmers to pass through a gate to access them. In other cases, there is no physical obstacle, with the restrictions being enshrined in military orders and practices.

[8] The differentiation between the two types of areas was explained by the Israeli authorities in a response to a petition file with the Israeli High Court of Justice (HCJ) in 2019: is based a landmark ruling by the Israeli High Court of Justice (HCJ) from 2006: HCJ 9593/04, Rashad Murad and others v. IDF Commander in Judea and Samaria.

[9] Estimate provided by UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

[10] Calculated as including all localities at less than 1,000 metres from the restricted area.

[11] Incidents of intimidation, trespass and access prevention that did not result in injuries or property losses are excluded.

[12] A petition with the Israeli High Court of Justice filed by Palestinians and an Israeli human rights organizations to halt this process is still pending (HCJ 825/19, Head of Turmusayya Village Council and others vs Minister of Defense and others).