Impact of the barrier on agricultural productivity

In 2002, following a wave of Palestinian attacks, including suicide bombings, Israel began building a Barrier with the stated aim of preventing these attacks. The vast majority of the Barrier’s route is located within the West Bank; it separates Palestinian communities and farming land from the rest of the West Bank, and contributes to the fragmentation of the OPT.

In its Advisory Opinion, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) established that the sections of the Barrier that run inside the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, together with the associated gate and permit regime, violate Israel’s obligations under international law. The ICJ called on Israel to cease construction of the Barrier inside the West Bank, to dismantle the sections already completed and repeal all legislative measures related to it.

Tayseer Amarneh from Akkaba, Tulkarm

February 2014: “Even saplings and plants need coordination before they are allowed to cross”

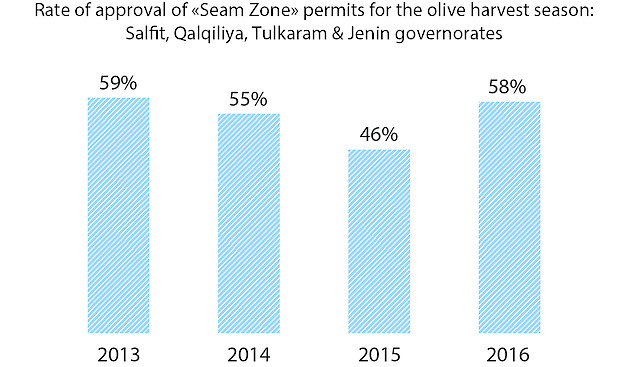

Tayseer Amarneh of Akkaba village in Tulkarm owns 230 dunums of land, mostly planted with olive trees. To access his land isolated between the Barrier and the Green Line, Tayseer requires a special permit. Data collected by OCHA over the past four years of olive harvests in the northern West Bank show a permit approval rate of about 55 per cent.

For those farmers granted permits, access to land behind the Barrier is through designated gates. During the 2016 olive harvest there were 84 gates, of which only 9 opened daily; 10 opened some days during the week and during the olive harvest; and 65 only opened during the olive harvest. The Akkaba gate used by Tayseer only opened three days each week for three periods of 15 minutes.

The limited allocation of permits, combined with the restricted number and opening times of the Barrier gates, impedes essential year-round agricultural activities such as ploughing, pruning, fertilizing, and pest and weed management. As a result, there is an adverse impact on olive productivity and value. Data collected by OCHA in the northern West Bank show that the yield of olive trees in the area between the Barrier and the Green Line has reduced by approximately 65 per cent in comparison with equivalent trees in areas accessible all year round.[8]

Tayseer explained: “There are complicated procedures at the gates regarding the type of agricultural materials and equipment we are allowed to take to our land behind the Barrier, and this directly affects the quality and type of work that we can carry out. Many times, the soldiers at the gate refused to let me pass with my tractor when I needed it to work on our land; it was the same with agricultural tools such as saws, which I need to prune my trees. They told me to go to the Palestinian DCO to coordinate to allow these materials to cross. When I wanted to carry fertilizer across, the soldiers told me to drop it on the ground for a security check and many times they refused to let it pass. Even saplings and plants need coordination before they are allowed to cross.”

Case published in February 2014 Humanitarian Bulletin

May 2017: “Some farmers are choosing not to plant because they are afraid of not obtaining a permit and losing their harvest”

OCHA revisited Tayseer in May 2017:

“In Akkaba, 223 residents are eligible for agricultural permits, including seasonal permits for the olive harvest. Since the beginning of 2017 only 27 permits are valid in the village. I used to have six employees to work on my land; now I have none because they cannot obtain permits because of the new regulations.[9] Only one of my sons has a permit but he is studying in the university and cannot help me except during the holidays, when the gate is usually closed. Nowadays, some farmers are choosing not to plant their land at all because they are afraid of not obtaining a permit and losing all their harvest.

Even if you receive a permit you are at the mercy of the soldiers who are responsible for opening and closing the gate. We sometimes wait for hours until the soldiers come and let us through. Agricultural tools, fertilizers and plants need pre-coordination to be allowed through the gate, which means that we call the Palestinian liaison officers, who call the Israeli liaison officer and coordinate the entry of the material. There are two Israeli military officers who open the gate, and the Border Police and army both need to be informed. Recently at the gate, the Border Police said that they had not received any written notification that I wanted to bring fertilizers onto my land while the army said that they had received it. They did not allow us carry the fertilizers through until a fax was sent from the Israeli liaison to the Border Police.

These policies are reducing the amount of land planted behind the Barrier as farmers are getting frustrated and do not want to take the risk of planting and then not receiving a permit to cultivate or harvest.”

[8] For further details on the methodology used for data collection see: Humanitarian Bulletin, February 2014, Impact of the Barrier on Agricultural Productivity in the Northern West Bank.

In 2016, there was a 74 per cent reduction in yield in Tayseer’s olive trees behind the Barrier in comparison with his trees on the ‘Palestinian’ side to which he has free access.

[9] These restrictions apply to a minimum area of land and land ownership documents are required before Palestinian landowners can apply for a permit to cross the Barrier. See Humanitarian Bulletin, April 2017, Increased restrictions on access to agricultural land behind the Barrier.