Restricted access to farming land taken over by settlers despite legal rulings in Israeli courts

The seizure of privately owned Palestinian land to establish and expand Israeli settlements has been a common phenomenon from the beginning of the Israeli occupation.[1] In recent years, these actions have been conducted primarily by Israeli settlers without an official permit or authorization, but often with the acquiescence and active support of the Israeli authorities. The resulting loss of property and sources of livelihood, restricted access to services, and a range of protection threats have triggered demand for assistance and protection measures by the humanitarian community.[2]

In several instances Palestinian landowners affected by settlement expansion, supported by human rights organizations, have won court rulings or administrative decisions that uphold their ownership of specific plots of land and order the removal of the settler trespassers or the revocation of seizure orders. However, these rulings have often remained “on paper”, with landowners unable to access or cultivate their land even after settlers have been evacuated.

Amona settlement outpost was established in an area belonging to Palestinians from Ein Yabroud village (Ramallah). In February 2017, following a protracted legal battle that ended with an Israeli High Court of Justice (HCJ) ruling in favour of the Palestinian landowners, the settlement was evacuated. Immediately after, the Israeli military issued a “demarcation order” forbidding entry to the area by any person (including both Israelis and Palestinians) for a period of two years.

In response to an appeal by Yesh Din on behalf of the landowners, the military stated: “In light of real concern of friction in the field”, entry to the area requires “prior coordination” and the policy for granting such coordination at this stage would be “very limited”.[3]

In recent years, the Israeli authorities have expanded the requirement of “prior coordination” as a condition for Palestinian farmers to access their land in the vicinity of settlements.[4]

This practice, which allows only limited access (a few days a year in most cases), undermines agricultural activities, endangers livelihoods and penalizes farmers affected by settler violence rather than enforcing the rule of law on violent settlers.

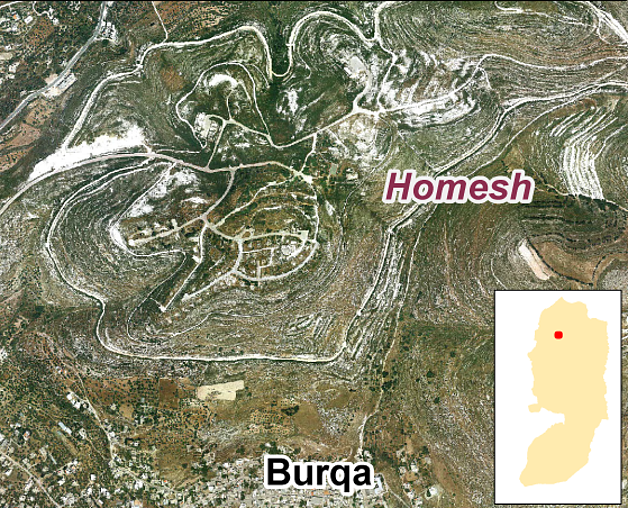

In other cases, Palestinian farmers have been discouraged or prevented from accessing their land in evacuated areas due to systematic violence and intimidation by Israeli settlers who are often armed. For example, in the case of private land belonging to Palestinians from Burqa village (Nablus), where the settlement of Homesh was established and then evacuated in 2005 (see case study).

There have been similar cases in which Palestinian landowners face formal or informal restrictions to access their land despite legal rulings reversing a takeover by settlers. These cases include the evacuated settlement outposts of Migron and Ulpana (Beit El), both in Ramallah governorate, and specific plots in or around the settlements of Ofra, Elon More and Shilo in the Ramallah and Nablus governorates.

The appropriation of private land for settlement activities violates a range of provisions under international humanitarian and human rights law. As highlighted above, although some Palestinians succeeded in establishing ownership via legal remedies, the translation of the legal rulings into facts on the ground has proved challenging. In some cases the Israeli government has attempted to retroactively regularize takeovers via new legislation.[5]

The Case of Burqa

The settlement of Homesh was established in 1978 on private land requisitioned from Palestinians from Burqa village for “military purposes”. As part of a disengagement plan, the settlement was evacuated in 2005 and most of the homes and infrastructure were demolished.[6]

Area affected by access restrictions and settler violence

The Israeli authorities did not revoke the military requisition order imposed on the land of the previous settlement but around a year later, the Palestinian Ministry of Agriculture initiated a land rehabilitation project to allow landowners to regain access and resume cultivation around the built-up area of the evacuated settlement, but not inside it.

From 2011, groups of Israeli settlers, reportedly from a nearby religious college (Yeshivat Homesh), began to visit the area regularly and attack or harass Palestinian farmers, block access to land and vandalize property. On various occasions, settler representatives claimed that access by farmers to the area was illegal because the land is still requisitioned for military purposes.

According to a landowner, Abu Kuteiba, a group of 8-12 Israeli settlers have moved into a nearby cave and in tents to monitor the area continuously. Whenever farmers try to access their land, settlers approach them, threaten them at gunpoint, hurl stones or physically attack them. On a few occasions when farmers tried to enter in larger numbers for safety, the settlers summoned the army, who sent the Palestinian farmers back on the grounds that the area is a closed military zone.

In May 2013 following a petition filed with the Israeli HCJ by Yesh Din on behalf of Burqa farmers, the Israeli authorities revoked the 1978 requisition order. A few months later, the authorities also revoked an order designating the area as a closed military zone, thereby removing all legal barriers to the access and use of the land by the owners. Despite these legal steps, the reality on the ground remains unchanged and the Israeli settlers have continued their activities unabated.

“If I had access to my land I would be making 8,000 NIS from the olive harvest”

Pointing to his land, Abu Kuteiba, land owner and father of three, explained: “In 2008, I planted 200 almond trees. In 2011, Israeli settlers uprooted all but 60 of them. Three years later I planted 150 olive trees; when they became three years old, Israeli settlers came and cut them, along with the 60 almond trees”

Pointing to his land, Abu Kuteiba, land owner and father of three, explained: “In 2008, I planted 200 almond trees. In 2011, Israeli settlers uprooted all but 60 of them. Three years later I planted 150 olive trees; when they became three years old, Israeli settlers came and cut them, along with the 60 almond trees”

“If I had access to my land, this time of the year, I would be making 8,000 NIS in profit from the olive harvest. We could be able to have a lot of projects in this land, like raising cattle, planting seasonal vegetables, etc. There are a lot of possibilities,” says Abu Kuteiba.

When asked about whether he had ever filed a complaint against Israeli settlers at the Israeli police station, following an attack, Abu Kuteiba explained:

“In April 2017, after being physically attacked by an Israeli settler, I filed a complaint at the Israeli police station in Huwwara, with the help of Yesh Din. I was also accompanied by a representative from the Palestinian District Liaison Office. I even had a photo of the Israeli settler who attacked me, which I took with my mobile. During the meeting, the Israeli officer said that the complaint will not bring anything good, on the contrary it will most likely trigger further problems regarding my ability to access my land, insinuating the issuance of orders effectively barring access to his land. I ended up withdrawing my complaint in fear of repercussions. The funny part is, when I applied for a magnetic card[7], I was rejected citing a police objection.”

* Protection Cluster partner, Yesh Din, contributed to this article.

[1] Until 1979, the main method used to establish Israeli settlements was by requisition of private Palestinian land for “military purposes”. However, a landmark ruling by the Israel Supreme Court forced the Israeli authorities to discontinue this practice and rely on so-called “state land”.

[2] See OCHA, “The humanitarian impact of de facto settlement expansion”, The Humanitarian Bulletin, February 2017.

[3] Letter from legal advisor to the West Bank to Attorney Shlomy Zachary from the legal staff of Yesh Din, 2 July 2017, in response to a request to coordinate a meeting with the petitioners in HCJ 9499/08 Maryam Hassan Abd al–Kareem Hamad v. the Minister of Defense.

[4] According to the Israeli authorities, the prior coordination of Palestinian access to certain areas is required to reduce friction and ensure the safety of Palestinian farmers.

[5] On 6 February 2017, the Israeli Knesset approved the Regularization Law, which provides for the retroactive legalization of settlements established without authorization on private Palestinian land, provided certain conditions are met. The implementation of the law has been suspended pending a ruling by the Israeli High Court of Justice.

[6] The disengagement plan entailed the unilateral evacuation of all Israeli settlements and military bases from the Gaza Strip, as well as four Israeli settlements in the northern West Bank.

[7] An Israeli-issued identification card is a prerequisite for a permit to enter occupied Palestinian territories otherwise barred to Palestinian residents of the West Bank and Gaza.