Gaza plunges into darkness: Severe deterioration in the energy situation

On 17 April, Gaza’s sole power plant (GPP) was forced to shut down completely after exhausting its fuel reserves and being unable to replenish them due to a shortage of funds. The shutdown occurred in the context of an ongoing dispute between the Palestinian authorities in Gaza and Ramallah on tax exemption for fuel and revenue collection from electricity consumers.

The electricity supply from Egypt, which normally accounts for 15 per cent of Gaza’s supply, also came to a halt on 24 April due to technical malfunctioning. Gaza is currently supplied only with electricity purchased from Israel, resulting in electricity blackouts of 20 hours per day, up from 12-16 hours previously. This undermines the delivery of basic services and is detrimental to already vulnerable livelihoods and living conditions.

Gaza has been affected by a chronic electricity deficit for over a decade. The situation deteriorated after June 2013 following the halt to the smuggling of cheaper Egyptian fuel, which was being used to operate the GPP. The subsequent increase in the cost of fuel[1] forced the GPP to operate only two of its four power-generating turbines. In 2015 and 2016, the GPP was forced to shut down completely on at least six occasions, for a total of over 46 days, due to a lack of financial resources to purchase fuel.

Electricity supplies purchased from Israel and Egypt have also been repeatedly disrupted. According to the Gaza Electricity Distribution Company (GEDCO), the Egyptian lines were completely down for an average of six days per month during 2016, while supply via Israeli lines was cut on at least one of the 10 lines for three to four days per month. Consequently, the electricity supply to Gaza since 2013 from all three sources has fluctuated constantly at between 20 to 50 per cent of the estimated demand.

Electricity supplies purchased from Israel and Egypt have also been repeatedly disrupted. According to the Gaza Electricity Distribution Company (GEDCO), the Egyptian lines were completely down for an average of six days per month during 2016, while supply via Israeli lines was cut on at least one of the 10 lines for three to four days per month. Consequently, the electricity supply to Gaza since 2013 from all three sources has fluctuated constantly at between 20 to 50 per cent of the estimated demand.

Due to the shortages, GEDCO operates an electricity rationing system entailing rolling power cuts of 12 to 16 hours per day on average across Gaza. These power cuts increase immediately to up to 18-20 hours per day when the GPP shuts down or when there are disruptions in the electricity lines from Israel and Egypt.

To maintain a minimum level of continuity of critical services, providers rely heavily on back-up generators. As with the GPP, the operation of generators is constantly at risk due to funding shortages for fuel purchase, plus limited fuel storage capacity, recurrent malfunctioning due to overuse, and challenges in procuring spare parts and new generators due to import restrictions imposed by Israel.

Impact on health services

Fuel storage and generator capacity varies greatly between health facilities. For example, Shifa Hospital, which is the main hospital in the Gaza Strip, consumes around 650 litres per hour but has the capacity to store 135,000 litres of fuel. Five of the 14 Ministry of Health (MoH) hospitals in Gaza were provided with double electricity lines by GEDCO, and some critical departments such as intensive care, kidney dialysis and neonatal care units are supplied with solar-based energy sources that may sustain services for few hours. Nevertheless, dependency on generators is critical to hospitals.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), without fuel to run generators, 40 surgical operation theatres, 11 obstetric operation theatres, 5 haemodialysis centres and hospital emergency departments serving almost 4,000 patients daily will be forced to halt critical services. The situation will immediately be life threatening for 113 newborns currently in neonatal intensive care units, 100 patients in intensive care and 658 patients requiring bi-weekly haemodialysis, including 23 children. Refrigeration for blood and vaccine storage will also be at risk.

To cope with the crisis, hospitals are working at minimal capacity and postponing elective surgeries; discharging patients prematurely after surgery; cancelling and reducing sterilization and cleaning services; and increasing referrals of patients outside of Gaza, particularly for chronic illnesses.

Health equipment is degraded and damaged by the constant fluctuations in the electricity current. According to the WHO, 200 critical medical machines and equipment are currently out of order and awaiting repair in Gaza. These items are necessary for critical departments such as hemodialysis units and ICU. The lack of a proper maintenance system (sterilization services) also reduces the life span of the existing medical equipment.

Impact on water and sanitation services

The poor supply of electricity and fuel to operate water pumps and wells reduces the quantity and frequency of the water supply to households; current supply stands at four to eight hours every four or five days. This has increased people’s reliance on private, uncontrolled water suppliers and lowered hygiene standards. In the Gaza municipality alone, 11 generators at the main water wells are currently out of order due to lack of spare parts to repair them. Spare parts for generators are often prohibited entry by Israel as they are included on the Israeli list of items classified as dual-use (civil-military).

A new seawater desalination plant, inaugurated in January 2017 in Khan Younis, was expected to provide its first phase of fresh water to 75,000 people in southern Gaza,[2] but it has been disrupted due to the lack of power supply and is only functioning on an ad hoc basis.

Wastewater plants also have shortened treatment cycles and 120 million litres of untreated sewage are discharged into the Mediterranean Sea every day. Additionally, there is a constant risk of the backflow of sewage onto streets if sewage pump stations fail. Fuel shortages to run vehicles have forced municipalities to significantly reduce refuse collection, which generates additional public health hazards.

Emergency fuel deliveries

Since December 2013 emergency fuel supplies from the international community to the most vital health, WASH and municipal facilities have prevented the collapse of these services.[3] By April 2017, 186 critical facilities had been targeted: 32 in the health sector; 124 in the water and wastewater sector; and 30 in the solid waste management sector.

OCHA has facilitated the prioritization exercise and discussions with the respective sectors, as well as coordinated on distribution. UNRWA takes responsibility for the purchase, delivery and distribution of the fuel.

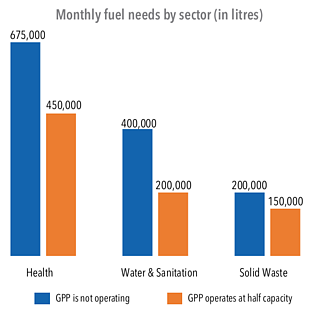

Emergency fuel required to maintain a minimum level of critical service delivery in the three sectors is estimated at between 0.8 and 1.4 million litres per month depending on the level of operation of the GPP and the quantity of supply through the Israeli and Egyptian feeder lines. The cost ranges between US $500,000 and $850,000 a month.

Emergency fuel required to maintain a minimum level of critical service delivery in the three sectors is estimated at between 0.8 and 1.4 million litres per month depending on the level of operation of the GPP and the quantity of supply through the Israeli and Egyptian feeder lines. The cost ranges between US $500,000 and $850,000 a month.

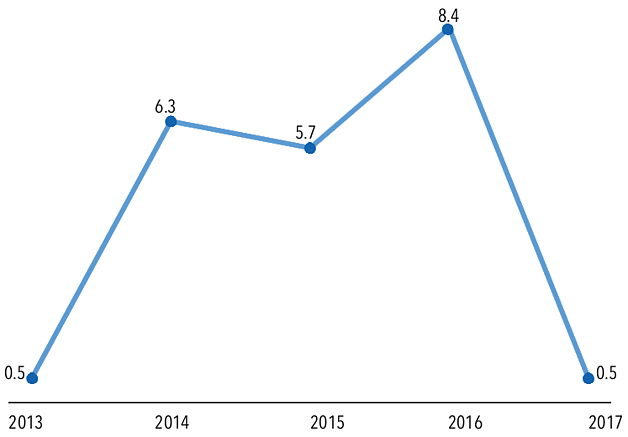

Following the premature exhaustion of fuel reserves, and given the lack of new contributions, on 27 April 2017 the OPT Humanitarian Fund, managed by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Coordinator, approved the allocation of $500,000 for the purchase of emergency fuel to maintain the delivery of essential services at hospitals and other emergency medical facilities. As a result, fuel reserves in all three sectors are expected to last for few weeks, assuming other power sources function at existing low levels.[4]

Allocation of funds for emergency fuel (in millions US$)

[1] Since 2013, fuel for the GPP has been purchased exclusively from Israel. The GPP needs approximately $12.5 million per month to procure sufficient fuel to operate at half capacity.

[2] For further information on this facility, see OCHA, Humanitarian Bulletin, February 2017.

[3] The initial emergency fuel deliveries started in November 2013 and consisted of around 200,000 litres per month, but gradually increased to an average of 365,000 litres in early 2014, and reached almost 1.5 million litres in August 2014 during the escalation of conflict. In 2015 it declined to an average of 480,000 litres due to the lack of long-term solutions. Demand for emergency fuel grew again and 700,000 litres per month were distributed by the end of 2016.

[4] If the GPP resumes operations at even partial capacity, emergency fuel purchased with HF funding may take several weeks longer to become exhausted.