Waste Away: Living next to a dumpsite

This article was contributed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

“The dump site here ruined our lives. The air we breathe isn’t clean and the environment we live in isn’t healthy,” said Abu Ahmad, a father of seven, who lives in Beit Lahia in northern Gaza, next to an informal dumpsite. “I love Beit Lahia. It used to be an agricultural area, where we could eat what we plant. The water was good as well. Now, the area is damaged, and the aquifer is polluted. I really hate saying this, but I wish I could leave.”

Solid waste management (SWM), including collection, transportation and disposal, is amongst the most critical challenges facing service providers in the Gaza Strip. As with other services, SWM has been undermined as a result of over a decade of the Israeli blockade, internal Palestinian divide and recurrent hostilities. Landfills and dumpsites are overloaded; there is lack of separation, sorting and recycling of trash; equipment is out of date and maintenance is irregular; the treatment of hazardous waste is defective; and the collection of fees is limited.

The situation has further deteriorated since the outbreak of COVID-19, due to the worsening of socio-economic conditions and the shrinkage of resources available to service providers, as well as the additional risks posed by the need to manage increased quantities of infectious waste.

Solid waste collection amidst a pandemic

Gaza’s two million people produce nearly 2,000 tons of waste a day. SWM services to this population are provided by ten municipalities, along with a Joint Service Council; together these employ some 1,200 staff. They rely on some 500 donkey carts, 76 waste collection vehicles and 23 other machines such as compactors and loaders.[1]

Currently, there is no specialized SWM system for infectious waste: this is collected by the same municipal staff, disposed in the same containers and transported to the same landfills as the regular solid waste. Consequently, although the spread of COVID-19 in Gaza has been largely contained, solid waste is a potential source of contagion.[2]

Due to the contraction of economic activity following the outbreak of COVID-19 and related restrictions, the average rate of recovery of municipal fees across the Strip declined from 22 per cent in January 2020 to just 13 per cent in April. To avoid a total collapse of services, on 28 April, the Council of the Gaza Strip Municipalities announced a reduction in the scope and frequency of all municipal services, including SWM, as well as a postponement in the payment of salaries to their staff.

Among other measures, municipalities were forced to reduce the funding allocated for the purchase of the fuel needed to run SWM vehicles and machinery. According to a recent assessment by the WASH Cluster, collection of solid waste has been suspended for 30 per cent of households in Gaza since late April, especially those located on the margins of urban areas.

This has resulted in the accumulation of tons of uncollected trash in some areas. Residents of these areas report that the smell intensifies as temperatures rise, with the air becoming toxic, compounded by outbreaks of flash fires and smoke. The accumulated trash also attracts stray dogs and cats, as well as rodents – all possible vectors of diseases, which has become an increasing safety concern, especially for children.

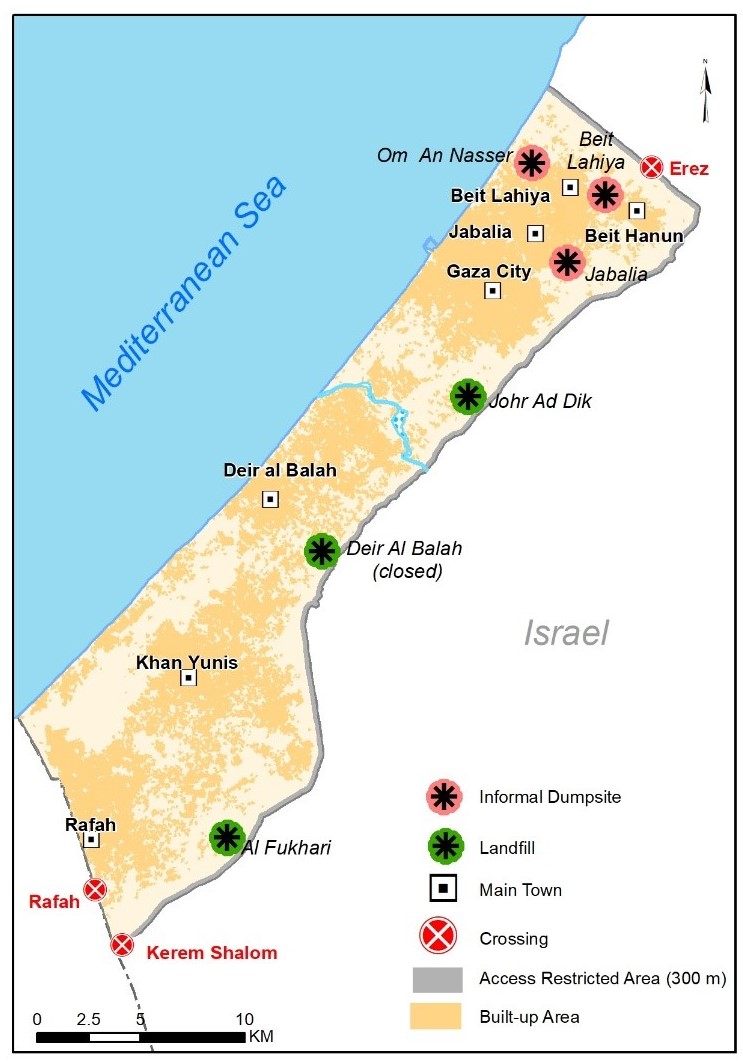

Currently, there are two official landfills operational in Gaza - Al Foukhari and Johar Ad Dik - both located at approximately 500 meters from the perimeter fence with Israel (see map). An additional landfill east of Deir Al Balah was closed in July 2019.

Given the access restrictions imposed by the Israeli army in areas along the fence, and the use of live ammunition to enforce restrictions, municipalities customarily notify the army in advance of the entry of trucks to these landfills, via the Palestinian Authority (PA). This practice has been discontinued since end-May, following the PA’s suspension of coordination with the Israeli authorities. As a result, municipal staff have reduced the frequency of their visits to the landfills for fear of being shot at; so far, no casualty has been recorded in this context.

The challenge of informal dumpsites

Abu Ahmad explained that he did not choose to live close to an unregulated dumpsite: “Our problems started in 2005 when our neighbourhood became a transfer point for trash. The situation has got worse since 2009, as it has gradually turned into an informal dumpsite and the amount of waste has increased.”

Beit Lahia is home to some 40,000 people, and its dumpsite is located on the margins of a residential area. It currently extends over 100 dunums and contains around 300,000 tons of waste. With an average addition of 160 tons every day, the site is expanding rapidly and getting closer to more densely populated areas. Another two large dumpsites exist in Umm al Nasser and Jabalia, also in northern Gaza (see map), with several smaller sites scattered across the Strip.

As stated in a study carried out by the World Health Organization (WHO), “inadequately disposed or untreated waste may cause serious health problems for populations surrounding the area of disposal.”[3] Research carried out in rural areas of the Hebron governorate in the West Bank identified a strong spatial association between burning sites for electrical and electronic waste (e.g. batteries, household appliances, computers) and the prevalence of childhood cancer lymphoma.[4]

“Now is the mosquito season and the insect bites cover our children’s faces,” Abu Ahmad complained. “Look at my daughter Salma: she is six years old and has been visiting doctors since she was born. She was bitten by an insect and now she has this mark on her face that doctors can’t treat.”

The public health hazard for both waste collectors and the people living in the vicinity of these informal sites is exacerbated due to the practice of dumping hazardous medical infectious waste, along with ordinary domestic waste. A particularly vulnerable group is the waste collectors (often children), who collect “valuables”, such as metal, plastic items, damaged electronics and furniture from waste containers along the streets, open transfer sites in the cities, and from the informal dumpsites.

According to a comprehensive study published by the UN Environment Programme in June 2020, leaching from solid waste that is unsafely disposed across the OPT has also contributed to the degradation of groundwater.[5]

Addressing the most urgent priorities

By 2040, the population of the Gaza Strip is expected to reach 3.2 million and produce a daily amount of about 3,400 tons of domestic waste, 1,200 tons of agricultural waste and 300 tons of commercial and market waste.[6] These projections highlight the immense challenges facing the SWM sector in Gaza, due not only to limited financial resources, but also to the limited availability of land.[7]

In the immediate term, however, the most pressing challenge is to secure the proper handling and treatment of infectious waste, in order to prevent a potential spread of COVID-19. The current practice of pouring chlorine over bags containing this waste prior to their transportation to landfills is considered ineffective and is not recommended.

After considering various alternatives, UNDP has opted for the introduction of a specialized microwave device as the main method for treating infectious waste. Following consultations with the Ministry of Health, the Environment Quality Authority and WHO, and with the financial support of the OPT Humanitarian Fund,[8] UNDP procured such a treatment unit with a 1.5-ton capacity, to be installed at the Johr Ad Dik landfill. However, due to the halt in coordination between the PA and Israel, the processing of the required importation documents has been delayed, impeding the delivery of the device from Belgium to Israel.

Additional items procured and installed as part of this project, with funding provided by Norway, included two industrial shredders, 12 waste sterilizers for hospital laboratories, and three infectious waste transport vehicles. This project is aligned with a longer-term programme for the management of medical waste, implemented by UNDP in partnership with the Government of Japan.

Irrespective of whatever solutions are provided for the treatment of infectious waste, the municipalities and the Joint Service Council need urgent financial support to increase the collection of solid waste and prevent further accumulation in the streets. Random dumpsites must be closed down and the waste transferred to the authorized landfills, with priority given to the three sites in northern Gaza. This also requires significant financial support for the procurement of equipment, including trucks.

[1] WASH Cluster, Rapid COVID-19 Solid Waste management assessment in Gaza Strip, May 2020.

[2] For updated information about COVID-19, see OCHA’s online dedicated page.

[3] WHO, Waste and human health: Evidence and needs, November 2015, p. 14.

[4] Davis, J.-M., & Garb, Y. “A strong spatial association between e-waste burn sites and childhood lymphoma in the West Bank, Palestine”, International Journal Cancer, 144(3), October 2018.

[5] UNEP, State of Environment and Outlook Report for the occupied Palestinian territory, 2020, p. 14.

[6] UNDP, Feasibility study and detailed design for solid waste management in the Gaza Strip, 2012.

[7] For a comprehensive analysis of the current situation and challenges ahead, see CESVI, Solid Waste Management in the OPT, September 2019.

[8] The OPT Humanitarian Fund is generously supported by Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, South Korea, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland.