Wadi Yasul: a community at risk of mass displacement

As reported in last month’s Bulletin, some 60 homes and other structures were demolished in East Jerusalem in April, due to lack of building permits. This is the highest number in a single month since OCHA began to systematically record demolitions in 2009. More people have already been displaced in East Jerusalem in the first four months of 2019 than in all of 2018.[1] Although no demolitions occurred in East Jerusalem in May, it has been the practice of the Israeli authorities to refrain from conducting demolitions during the month of Ramadan and demolitions are expected to resume after the Eid holiday in June.

Demolitions must be seen in the context of the restrictive planning regime in East Jerusalem, which makes it impossible for Palestinians to meet their basic housing and infrastructure needs. Only 13 per cent of the territory annexed by Israel following the 1967 occupation is currently zoned by the Israeli authorities for Palestinian construction.[2] However, much of this land is already built-up, the permitted construction density is limited, and the application process for obtaining building permits is complicated and expensive. Between 1967 and 2012, 4,300 permits were issued by the Jerusalem Municipality for Palestinian areas of East Jerusalem, an average of less than 100 permits a year.[3] During the same period, the Palestinian population grew by more than 200,000, culminating in an estimated gap of 900-1,100 housing units per year between legally permitted construction and the number of units needed to meet population growth.[4]

As a result, unlicensed construction has been widespread, both within the 13 per cent and in locations where Palestinian construction is completely prohibited, such as unplanned areas (30 per cent of land in East Jerusalem) or areas designated as “green” or for roads and other public infrastructure (22 per cent).[5] It is estimated that at least one third of all Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem lack an Israeli-issued building permit, potentially placing over 100,000 residents at risk of displacement. Those who build without the requisite building permit face the threat of demolition, displacement and other penalties, including costly fines, confiscation of building equipment and possible prison sentences.

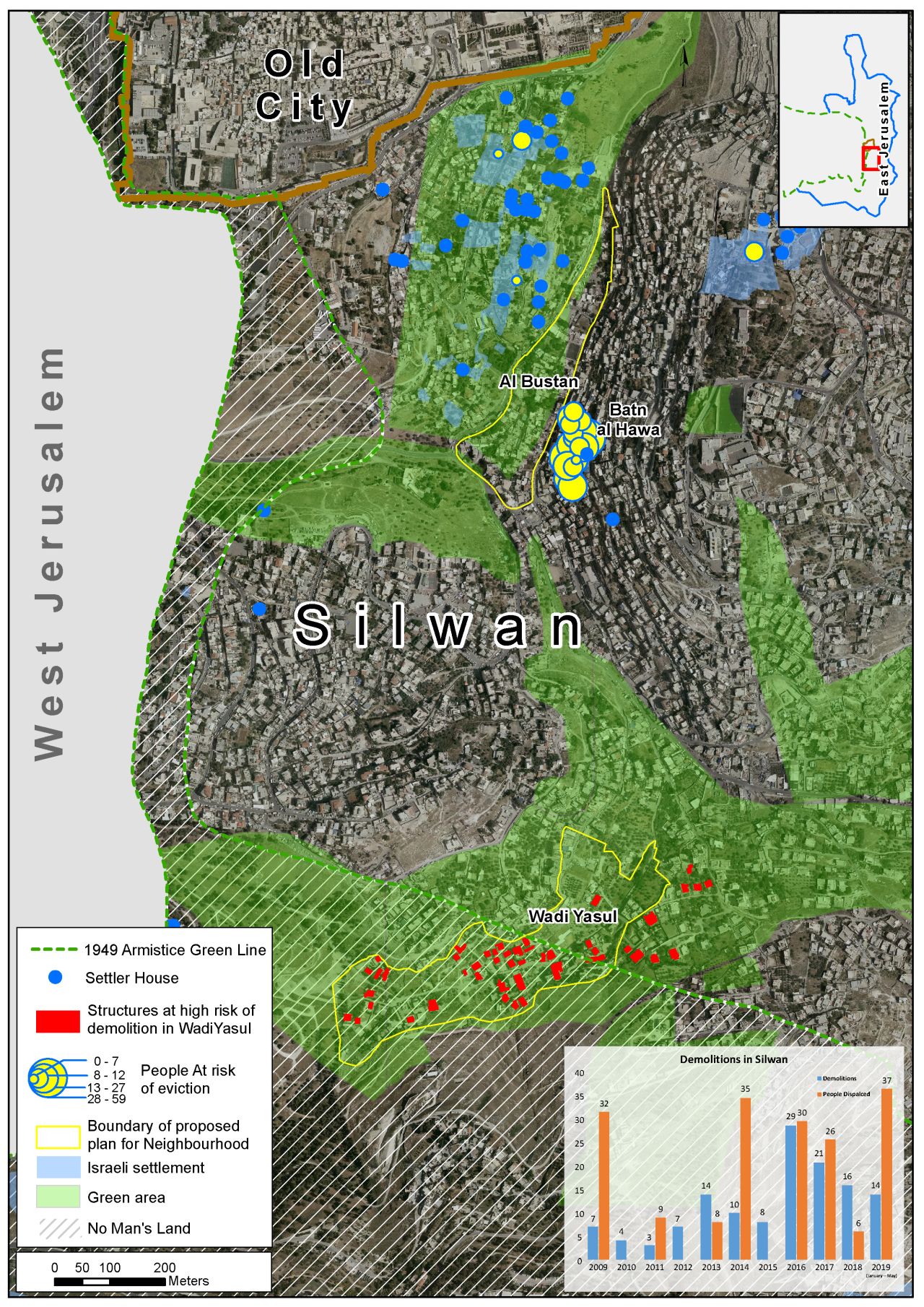

Entire neighbourhoods exist that are inadequately planned, under-serviced, have severely reduced space for development, and face the threat of demolitions and displacement. One such neighbourhood is the Wadi Yasul area of Silwan, located just south of the Old City of Jerusalem between Jabal al Mukabbir and At-Thuri (see map on page 10). Wadi Yasul is home to some 700 Palestinians but has been zoned by the Israeli authorities as a ‘green area’, specifically forest, since the late 1970s.[6] Efforts by residents over the past 15 years to rezone the neighbourhood as “residential” have so far been rejected. The District Planning Committee has maintained that Wadi Yasul should remain ‘green’ due to its proximity to the Old City, in line with the Local Outline Plan for Jerusalem 2000, and that unlicensed Palestinian homes therein should be demolished.

The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is currently handling 62 legal demolition cases in Wadi Yasul; 50 of these cases will be heard at the District Court on 12 June. The risk of demolition is imminent: these cases have exhausted almost all domestic legal remedies and their outcome is linked to a District Court ruling on 31 March 2019 that dismissed three similar cases in Wadi Yasul, and to a subsequent decision by the Supreme Court on 14 April 2019 to deny a request by the residents’ lawyer to appeal the dismissal of these cases.

In parallel, residents have, for the third time, retained a planner to initiate a new spatial plan for their community. This was submitted to the National Planning Council on 19 February 2019 and a decision is pending. Ahead of the June District Court session, the community’s planner and lawyer will also meet with the municipality to discuss planning venues that would protect the community from the threat of mass demolition. If these demolitions are executed, around 500 people living in 50 residential buildings, around twenty per cent of them registered Palestine refugees, will be at risk of displacement in Wadi Yasul. Under International Humanitarian Law, the occupying power has the obligation to respect lives and private property[7] and is prohibited from destroying property except where such destruction is rendered “absolutely necessary by military operations”.

A number of structures in Wadi Yasul have already been targeted: a stable and a warehouse were demolished on 17 April. Also on 30 April 2019, Israeli security forces demolished two residential structures in Wadi Yasul, displacing 11 people. Five people were seriously injured by Israeli forces using physical force, stun grenades and sponge-covered bullets in the course of the operation as residents tried to retrieve belongings prior to the demolitions. Anas Burqan, whose home was destroyed, was injured with a sponge-covered bullet to his back and subsequently arrested (see personal story: “It’s difficult to carry on”).

Silwan neighbourhood

Silwan is one of the Palestinian neighbourhoods most under pressure in East Jerusalem due to overcrowding, inadequate services, and the threat of demolition and displacement from unauthorized construction. As with Wadi Yasul, the al Bustan area of Silwan has been designated as an ‘open’ or ‘green’ area where all Palestinian construction is prohibited. Al Bustan is the proposed site of a tourist park to be constructed by the Jerusalem Municipality: if this plan is implemented, more than 1,000 Palestinians residing in approximately 90 houses will lose their homes.

Silwan is one of the areas in East Jerusalem most targeted by Israeli settler organizations, who are taki control of Palestinian properties and establish settlement compounds. The establishment of many of these settlement compounds has involved the forcible eviction and displacement of Palestinian residents, with a negative humanitarian impact. It has also generated a coercive environment on the daily lives of Palestinians residing in the vicinity of these compounds by creating pressure on them to leave. The main elements of this environment include increased tension, violence and arrests; restrictions on movement and access, particularly during Jewish holidays; and a reduction in privacy due to the presence of private security guards and surveillance cameras

Personal story: “It’s difficult to carry on.”

On 30 April 2019, Israeli forces carried out two residential demolitions in Wadi Yasul, displacing two refugee families consisting of 11 people, including seven children. Anas and Qusay Burqan are brothers who lived opposite each other on land owned by their father before their houses were demolished. The Burqan families were among the three cases, supported by NRC, which were dismissed by the District Court on 31 March.

According to Qusay Burqan, a father of three: “On the day of the demolition, the children were on their spring break and my first concern was to wake them up and send them to my in-laws’ house with my wife. I didn’t want them to see their house being demolished. No child should witness that.”

“We had never seen something like this before: Israeli forces came at 5:30 in the morning with more personnel than we could count. The operation quickly escalated into violent clashes with beatings, stun grenades and sponge-covered bullets. We were trying to get the furniture out of the houses but they didn’t give us a chance. Five of our neighbours who came to help were injured that day. I was knocked unconscious. My brother Anas, who was trying to collect his furniture and valuables, was shot with sponge-covered bullets, detained and fined. He was also placed under house arrest and banned from entering Wadi Yasul for 15 days. It was clear that nothing could stand in their way.”

Qusay subsequently rented an apartment of 50 square metres in at-Tur and the family now live there without a living room or a safe space for the children to play. He is unemployed.

“Once I knew that the demolition was imminent, I tried to prevent it and spent my time following up with the municipality and the lawyer. I couldn’t continue with work as a driver and my boss fired me. Most of our belongings were destroyed: everything was under the rubble. My children lost their school books and I cannot replace these books at this time of the school year. It’s difficult to carry on”.

Personal story: “There’s a constant fear hanging over our heads.”

Jamileh Suleiman Awad is a 54-year-old mother who moved to Wadi Yasul almost 30 years ago when the family bought a piece of land there.

“My kids were young and I gave birth to my younger sons after we moved to Wadi Yasul. We have many memories here. We worked so hard to be able to afford our own piece of land. At the beginning in Wadi Yasul, there was no water or electricity. We brought it all. I remember my father-in-law used to carry water on donkeys. Every time a neighbour moved in, we would help them get electricity and water. This is how it all began. People in Wadi Yasul became one family rather than just neighbours.”

In 1991 the family received their first fine for building without a permit and they paid out NIS 85,000 over the years. They received additional fines every time they added a fence or a structure. Like many other families in this tightly-knit Palestinian community, Jamileh and her husband have their sons’ families living with them in the family home.

“We all live together, close to each other. It’s crowded but we don’t have a choice. My sons can’t afford to rent independently so we built a second and a third floor; we divided the apartments so that there’s space for all of us.”

Like most of the residents of Wadi Yasul, Jamileh’s family house is at risk of demolition. “There’s a constant fear hanging over our heads. If they go ahead with the demolitions, we’ll be separated and I don’t know how to plan for that.”

Jamileh’s husband, Suleiman, adds: “In Wadi Yasul we’re all in the same boat. None of us have permits to build. I want to remain hopeful because we simply have nowhere else to go. We just wish we had the same rights as settlers have; we see them building and expanding with no obstacles. It’s not fair”.

[1] On 3 May a joint statement was issued by the Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and UNRWA to call for “an immediate halt to the Israeli authorities’ destruction of Palestinian-owned property in East Jerusalem”.

On 26 April, the EU mission in Jerusalem and Ramallah also issued a statement calling on Israel to reconsider the execution of demolition orders in Wadi Yasul and reiterating its strong opposition to Israel’s settlement policy.

[2] Following the June 1967 occupation of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, Israel unilaterally annexed an area of 70 km² referred to as East Jerusalem. This unilateral annexation of EJ is an illegal acquisition of territory by the use of force. It contravenes Israel’s obligation as an occupying power under IHL not to irreversibly alter the status quo of the occupied territory, and it has not been recognized by the UN and the international community.

[3] Bimkom. 2015. Trapped by Planning, page 68.

[4] OCHA, The Planning Crisis in East Jerusalem, 2009, pp. 2 and 20.

[5] The remaining 35 per cent has been expropriated for Israeli settlements in spite of the IHL prohibition on the transfer of the occupying power’s civilians into occupied territory.

[6] Concurrently, the El Ad settler organization has built unlicensed camping and tourist structures in the vicinity of Wadi Yasul in the ‘Peace Forest’ and there are ongoing municipal efforts to change the zoning of the area. This would enable the retroactive legalization of these structures and facilitate the development of a proposed tourist settlement project. Nir Hasson, Jerusalem to Demolish Palestinian Homes in ‘Peace Forest’, Let Settlers Build, 14 April 2019. Also see Ir Amim, Demolitions in Wadi Yasul Symbolize Politically Motivated Discrimination in Planning, 17 April 2019.

[7] The regulations to Hague Convention IV: “Art. 46. Family honour and rights, the lives of persons, and private property, as well as religious convictions and practice, must be respected.”