Increased restrictions on access to agricultural land behind the Barrier

In recent months, increased restrictions have been reported in the northern West Bank which are affecting the access of farmers to their agricultural land isolated by the Barrier. These restrictions relate to a minimum area of land and land ownership documents required before Palestinian landowners can apply for permits to cross the Barrier. Although these restrictions have been included in previous ‘Standing Orders’ published by the Israeli authorities, which detail the regulations governing access to areas behind the Barrier, the concern is that stricter application of regulations will further restrict Palestinian access to agricultural land and livelihoods in Barrier-affected areas.[1]

In the northern West Bank, the land between the Barrier and the Green Line, the “Seam Zone,” was declared closed by military order in October 2003. All non-resident Palestinians above the age of 12 who need to enter this area, including for agricultural purposes, are required to obtain a special permit.[2] To apply or renew a permit, the applicant must satisfy the security considerations necessary for all Israeli-issued permits. Many farmers are rejected on those grounds, without further explanation.

Applicants must also prove a connection to the land in the closed area by submitting valid ownership or land taxation documents. Some applicants are rejected on the grounds of ‘no connection to the land’ or ‘not having enough land.’ In the West Bank, the majority of land is not formally registered and ownership has been passed over generations by traditional methods which do not require formal inheritance documentation, but still constitutes a major source of income for succeeding generations. OCHA monitors the rate of permit applications, particularly during the annual olive harvest when, according to the Israeli authorities, “recognizing the uniqueness and significance of the olive harvest season, agricultural employment permits beyond the set quota can be requested for members of the farmer’s family.”[3] In the northern West Bank, the approval rate for permit applications increased from 46 per cent in 2015 to 58 per cent in the 2016 harvest, totaling 6,707 approvals. Despite the increase, some 4,700 applications by farmers for this olive harvest were rejected.

Recent regulations on permits

In February 2017, a number of Palestinian District Civil Liaison Office (DCL) offices in the northern West Bank (Jenin, Qalqiliya, Tulkarm and Salfit) reported that they had been informed by their Israeli counterparts that registered owners with less than 330m2 of land are ineligible for a permit. The new regulations were not communicated officially but in conversations between the Israeli DCL and their Palestinian counterparts. If rigorously applied, the full impact of the measure on the already restricted pool of permit holders will only become apparent gradually as existing permits expire: it is estimated that some 55 per cent of current permits will expire in the four northern West Bank governorates during the course of 2017. In protest at the new regulations, the Palestinian DCL offices are refusing to accept applications for new or renewed permits, and are redirecting them to the Israeli DCL offices, who in turn are refusing to accept the applications.

Closure of key agricultural gate in Qalqiliya area

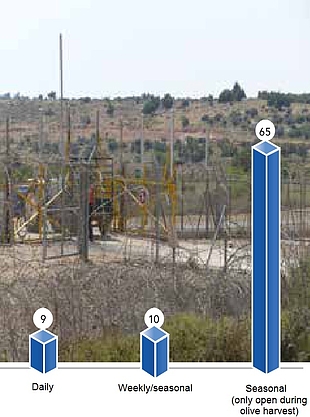

For those granted permits, entry to the area between the Barrier and the Green Line is through a gate designated on the permit. During the 2016 olive harvest, there were 84 gates along the completed sections of the Barrier, of which only nine open daily; 10 open some days during the week and during the olive harvest; and 65 only open during the olive harvest, prohibiting year-round access. The limited allocation of permits, together

For those granted permits, entry to the area between the Barrier and the Green Line is through a gate designated on the permit. During the 2016 olive harvest, there were 84 gates along the completed sections of the Barrier, of which only nine open daily; 10 open some days during the week and during the olive harvest; and 65 only open during the olive harvest, prohibiting year-round access. The limited allocation of permits, together

with the restricted number and opening times of the Barrier gates, have severely curtailed agricultural practices and undermined rural livelihoods throughout the West Bank.[4]

In addition to restricted or erratic opening hours, gates can also be closed indefinitely. The Beit Amin gate (1447) in Qalqiliya, which opened daily to serve between 100-200 farmers, has been closed since January 2017. Famers are being re-directed to another gate, normally reserved for military purposes, some 5.5 kilometres away, adding considerably to the length of time farmers require to reach their land.

The case of Ahmad

Ahmad (pseudonym), a farmer from Izbat Salman in the Qalqiliya area, is 43-year-old father of three. The most fertile area of his 200 dunums of land, about 40 dunums, was destroyed during the construction of the Barrier in 2013, including lemon trees and greenhouses. Between 2003 and 2010, he was repeatedly refused a permit on security grounds, despite having never been arrested. Thereafter, a permit was granted for land registered within his father’s land for varying periods of six months to one year. In 2015 he bought a new plot of land comprising 45 dunums behind the Barrier. Although the new plot is registered in his name, he is unable to apply for permits for family members or additional workers due to the current situation of non-cooperation in the Palestinian and Israeli DCLs.

The case of Basim

Basim (pseudonym), a farmer from Beit Amin, grows 25 dunums of za’atar (thyme), a herb widely used in Palestinian cuisine, on his land behind the Barrier. The crop is his main source of income with each three-month harvest worth $ 9,700. The closure of the Beit Amin gate has forced him to hire a taxi to take him to the alternative military gate and he then has to walk several kilometres along the Barrier patrol road to reach his land. B can now access his land less frequently and estimates that he has lost approximately half of his income since the new gate arrangements were introduced.

The International Court of Justice Advisory Opinion

In 2002, the Government of Israel approved construction of a Barrier with the stated purpose of preventing violent attacks by Palestinians in Israel. However, 85 per cent of the route does not follow the internationally recognized 1949 Armistice (Green Line), instead deviating inside the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. The inclusion of Israeli settlements behind the Barrier, citing security concerns, was the single most important factor behind the deviation of the route from the Green Line.

In 2004, the ICJ, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued an Advisory Opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory. The ICJ stated that the sections of the Barrier route which run inside the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, together with the associated gate and permit regime, violated Israel’s obligations under international law. The ICJ called on Israel to cease construction of the Barrier ‘including in and around East Jerusalem’; dismantle the sections already completed; and ‘repeal or render ineffective forthwith all legislative and regulatory acts relating thereto.’[5]

[1] The most recent version of the Standing Orders, the fifth, was published in March 2017, in Hebrew only.

[2] In January 2009, the closed area designation was extended to all or part of areas between the Barrier and the Green Line in the Salfit, Ramallah, Bethlehem and Hebron districts, plus to various areas between the Barrier and the Israeli-defined municipal boundary of Jerusalem. A petition dating back to the introduction of the permit regime in 2003 and challenging the legality of the Barrier permit regime under international and domestic law was rejected by the Israeli High Court of Justice in April 2011.

[3] Unofficial translation from fifth Standing Order.

[4] Data collected by OCHA over the last three years in the northern West Bank show that the yield of olive trees in the area between the Barrier and the Green Line has reduced by approximately 65 per cent in comparison with equivalent trees in areas which can be accessed all year round.