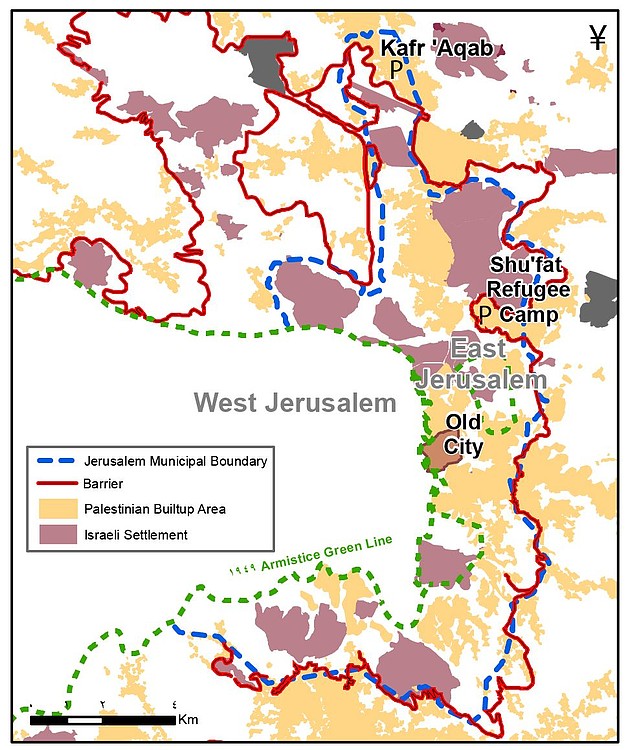

The impact of the barrier on the Jerusalem area

Following a wave of Palestinian attacks, including suicide bombings, Israel began building a Barrier in 2002 with the stated aim of preventing such attacks. The Barrier’s deviation from the Israeli-declared municipal boundary of Jerusalem has resulted in some Palestinian localities in East Jerusalem, especially Kafr Aqab and Shufat camp area, becoming separated from the urban centre. Although residents retain their permanent residency status and continue to pay municipal taxes, these areas have effectively been abandoned by the municipality.

Basic facilities and services are degraded or lacking entirely so residents need to cross checkpoints to access the health, education and other services to which they are entitled as residents of Jerusalem. The Palestinian Authority has no jurisdiction in these areas, and the Israeli police and municipality staff seldom enter municipal areas beyond the Barrier, thereby creating a security vacuum manifested in unsupervised wildcat building, and an increase in lawlessness, crime and drug trafficking.

Samih Abu Ramila, from Kafr ‘Aqab, East Jerusalem

August 2010: “Residents pay municipal taxes… but the municipality wants us to arrange the services by ourselves”

“When the Wall was erected, Jerusalem ID holders from neighbouring areas in the West Bank such as Bir Nabala and Ar Ram moved here to Kafr Aqab to maintain their ‘centre of life’ in the city and avoid having their ID card revoked. As the Jerusalem Municipality failed to allocate resources accordingly, services were insufficient to meet the increased needs. However, all these new residents were paying the municipal tax, the arnona, and expected services in return. Residents were dissatisfied with the community centre comprised of people appointed by the municipality. That is why a group of young people, including myself, started looking for alternative ways to serve residents’ needs without challenging, but rather cooperating, with the established political system. We founded an organization, the Company for the Development of Kafr Aqab, to look after the interests of residents and to act as a bridge between residents and the municipality.

When we complained to the municipality about the lack of educational facilities and the fact that our children had to cross the Wall to go to school, we were encouraged to arrange everything by ourselves as with the health clinic - the Al Bayan Health Centre which we established. Two businessmen and I invested money in the project. We found a suitable building which had a building permit, carried out some renovation work to make it comply with security and health standards, and hired teachers. The municipality came to check it and decided to cover part of the expenses, namely the salaries of the staff, and gave us a status as ‘recognized unofficial.’[2] As ninety percent of the teachers come from the West Bank, where they are paid less than teachers in Jerusalem, we retain a portion of their salaries to run the school. The rest is covered by student fees and donations from international organizations. Today the school serves 2,300 students from kindergarten to 12th grade. However, there are 1,500 pupils from Kafr Aqab enrolled in schools in areas outside the municipal boundary, such as Ramallah, and 2,200 children who are not enrolled in any school at all.”

Published in March 2011 East Jerusalem Special Focus Report

May 2017: “The school is being punished for keeping our children off the streets”

“In the intervening years, the school has expanded significantly to cater for 4,000 pupils, both boys and girls, spread over seven buildings,” Samih told OCHA in May 2017. “It still retains its ‘recognized unofficial’ status, with the Israeli Ministry of Education covering only 75 per cent of the teachers’ salaries. Because the school is registered as a private company, it must obtain a certificate of ‘good conduct’ every year from the Israeli authorities. This approval has been contested on the grounds that the company is not paying the teachers their full salaries as required by Israeli law. In 2016, one of the Israeli officials involved in the inspection process demanded a bribe in return for ‘good conduct’ clearance.[3]

The ‘good conduct’ certificate was refused in January 2017, with the result that the teachers stopped receiving their salaries from the beginning of the year. The Jerusalem Municipality maintains that it lacks the means to take over the school and absorb all the costs so the school faces the prospect of being closed down. I feel as if the school is being punished for keeping our children off the streets and for trying to provide an education for them instead of letting them remain ignorant and uneducated. I am a victim of this conflict between the Israeli Ministry of Education and the Jerusalem Municipality. I understand that the Palestinian Authority cannot officially operate in Kafr Aqab while it remains officially part of Jerusalem under Israeli law, yet I also feel that they have a responsibility to try to find a solution to our problem.”

[2] Some private schools are recognized ‘unofficially’ by the Israeli authorities and supported financially by the municipality to compensate for the shortage of classrooms in the municipal system. Other, more-recently established ‘recognized official’ schools, are termed ‘contractors’ by the other providers in that they are considered primarily profit-driven and receive most of their expenses from the municipality.

[3] The case was the subject of a report on the Israeli Channel 10 programme.