Gaza: water and sanitation services severely disrupted due to the energy crisis

Emergency responses and structural solutions urgently required

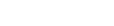

On 1 November, the Gaza Power Plant (GPP) shut down, due to the ongoing fuel shortage and depletion of its fuel stocks, triggering one of the most serious energy crises in the Gaza Strip in recent years, with potentially serious humanitarian ramifications. At present, Gaza relies on electricity bought from Israel (120 megawatts-MW) and Egypt (30 MW), which covers roughly 38 per cent of the demand. Therefore, families in Gaza are facing power outages of around 16 hours per day. The current fuel crisis has compounded an already fragile humanitarian situation generated by the longstanding Israeli restrictions and more recent measures imposed by the Egyptian authorities, in the context of security concerns in the Sinai. The Egyptian actions include the closure or destruction of smuggling tunnels between Egypt and Gaza, and increased restrictions on the movement of people and goods through the Rafah Crossing, which had become the main entry/exist point for Gaza residents, given the longstanding restrictions imposed by Israel at Erez Crossing.

On 1 November, the Gaza Power Plant (GPP) shut down, due to the ongoing fuel shortage and depletion of its fuel stocks, triggering one of the most serious energy crises in the Gaza Strip in recent years, with potentially serious humanitarian ramifications. At present, Gaza relies on electricity bought from Israel (120 megawatts-MW) and Egypt (30 MW), which covers roughly 38 per cent of the demand. Therefore, families in Gaza are facing power outages of around 16 hours per day. The current fuel crisis has compounded an already fragile humanitarian situation generated by the longstanding Israeli restrictions and more recent measures imposed by the Egyptian authorities, in the context of security concerns in the Sinai. The Egyptian actions include the closure or destruction of smuggling tunnels between Egypt and Gaza, and increased restrictions on the movement of people and goods through the Rafah Crossing, which had become the main entry/exist point for Gaza residents, given the longstanding restrictions imposed by Israel at Erez Crossing.

As of November, the supply of fuel through the tunnels has come to an almost complete halt. In recent years, Gaza had become dependent on smuggled, subsidized Egyptian fuel, with approximately 1 million litres per day entering Gaza through the tunnels until June 2013. The lack of an agreed mechanism between the Palestinian authorities in Ramallah and Gaza allowing for the purchase of (more expensive) fuel from other sources, including Israel, has further complicated the situation.

While all essential services are affected, one of the hardest hit is the water and sanitation sector, as none of its 291 facilities are functioning adequately.1 Due to electricity shortages, back-up generators need to be used more often, requiring more fuel, which is neither readily available nor affordable. Equipment that is increasingly affected by overuse and fluctuations in the power supply requires more frequent repairs. The largest sewage pumping facility in Gaza overflowed and at least ten other sewage pumping facilities are on the verge of overflowing. When there is a power outage, sewage facilities need to divert the bulk of the sewage to emergency lagoons, many of which have weak embankments, and discharges are increasingly difficult to control.

Before the most current crisis, some 90m3 of raw or partially treated sewage flowed into the Mediterranean Sea every day; now all sewage emanating from Gaza it is untreated, creating ever-growing pollution, public health risks and economic challenges. Significant investment in sewage treatment facilities was already required prior to the latest crisis, as new facilities need to be built and older ones refurbished, to cope with current demand. To deal with the needs of Gaza’s urban population, strategically placed treatment facilities and a complete upgrade of the water and sewage network are needed.

The energy crisis has also affected the quantity and quality of water, with water consumption reduced to 40 litres per person per day (l/p/d) on average, well below the 70-90 l/p/d recorded earlier this year and the recommended 100 l/p/d. Just 15 per cent of people in Gaza receive water daily, for five to six hours, and it is increasingly difficult to pump water to the upper floors of buildings.

Due to a longstanding practice of over-extraction from the underlying coastal aquifer, alongside sea water seepage, over 90 per cent of the water supplied to households via the network is not potable, requiring people to purchase desalinated water for drinking and cooking purposes. In November, water desalination units operated by the Coastal Municipalities Water Utility (CMWU) saw their capacity reduced by 75 per cent due to power shortages, forcing many households to obtain their desalinated water from private and unregulated sources. This month, nearly 900,000 complaints were made to the CMWU on the lack of municipal water provision and sewage treatment.2

Small quantities of fuel have been distributed to alleviate the immediate emergency. This fuel was provided through emergency funding by the Turkish government, which aims to provide 800,000 litres of fuel to the most critical sewage, solid waste and health facilities for a period of four months (200,000 litres per month).

In the absence of energy from the GPP, the WASH sector needs approximately 400,000 litres of fuel per month to maintain a reasonable level of functioning, the solid waste sector 150,000 litres and the health sector 500,000 litres. Therefore, until additional electricity feeder lines are established there is a need for a more structural solution.3

These solutions should include a clearly identified administrative settlement between Ramallah and Gaza to purchase additional fuel through Israel, at an agreed price. Additional measures discussed include better collection of outstanding electricity bills and the installation of pre-paid electricity meters for consumers in Gaza. While the payment of electricity bills in Gaza had improved prior to the energy crisis, the lack of service provision threatens to undercut progress made on that front.

3,000 affected by sewage overflow

On 13 November, one of the main sewage pumping stations in Gaza City (which previously handled 60 per cent of the city’s sewage) failed and discharged over 35,000 m3 of untreated sewage over a large area in the neighborhood of Az-Zeitoun, south of Gaza City. Approximately 3,000 people were directly or indirectly affected and exposed to public health risks, including diarrhea. By the time of publication, the sewage spill had not yet been addressed and clean-up operations had not started. Six school compounds located in the vicinity of sewage pumping stations are at risk of being flooded if there are additional overflows.

- This includes 205 water wells, 42 main sewage pumping stations, 15 districts sewage pumping stations, 4 wastewater treatment plants, 10 main water desalination plants and 15 water lifting stations with reservoirs. ↩

- Information provided via the UNICEF-led WASH Cluster. ↩

- There are indications that negotiations are underway between the PA and Israel to purchase another 100 MW of power for Gaza. However, a longer-term solution to provide Gaza with the required 450MW – needed for the energy deficit now and to address the water crisis through energy-intensive desalination projects – is still lacking. ↩