Gaza energy crisis: limited improvement in water and sanitation indicators; concerns over waterborne diseases remain

* The WASH Sector contributed to this article.

Ongoing electricity outages of 18-20 hours a day across the Gaza Strip throughout September and October continue to undermine the provision of basic services. In the water, sanitation and hygiene sector (WASH), sustained efforts by humanitarian agencies to provide 154 critical facilities with emergency fuel to run backup generators resulted in a limited improvement in some key indicators during September compared with previous months. There was a modest increase in the quantity of piped water supplied to households and in the functioning of desalination plants, plus a slight decline in the contamination levels of sewage discharged to the sea. Nevertheless, September indicators remain well below the already poor standards recorded during the first quarter of 2017.[1]

Although funding for emergency fuel has been satisfactory, other urgent interventions in the WASH sector remain underfunded and render the overall situation extremely precarious. The Gaza Urgent Funding Appeal launched in July 2017 requesting $25 million for interventions in the water and sanitation, health and food security sectors faces a gap of $10.8, all for the non-fuel related requirements. Agencies operating in the WASH sector estimate that approximately 1.45 million people in the Gaza Strip are at risk of contracting waterborne diseases from the consumption of unsafe water. During the winter months, the risks and consequences of winter flooding could impact an estimated 500,000 people.

Water supply for domestic consumption

Electricity cuts since April 2017 directly interrupt supplies of piped water through municipal networks as they reduce extraction of underground water from wells, hamper the operation of equipment to pump water through the network, and, due to the low pressure, from the network to water tanks on the rooftops of homes, particularly in multi-story buildings. In recent months, piped water has been supplied for 4-6 hours every three to five days in most areas.

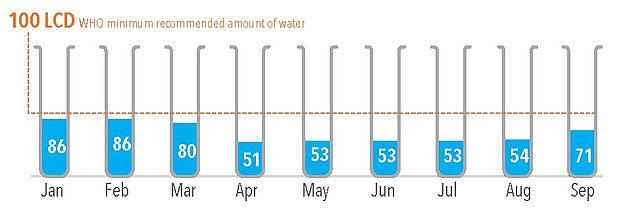

Access to piped water

Litres per capita per day

Due to an increased supply of emergency fuel, the average quantity of water supplied to households during September was 71 litres per day per capita (l/d/c), an increase of 34 per cent compared with the monthly average during April to August, but still well below the equivalent figure in the first quarter of the year (84 l/d/c), and far below the internationally recommended standard of 100 l/c/d.[2]

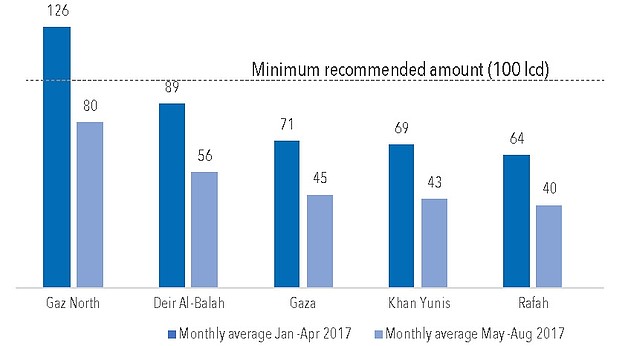

These figures are averages for all of the Gaza Strip but they conceal wide variations by area. For example, supply in Rafah governorate in July 2017 was 40 l/d/c, half of the equivalent figure in the Northern Gaza governorate (80 l/d/c). Since the aquifer extraction plant is located West of the Gaza Strip, creating further distance to Rafah, the low pressure of water requires electrical pumping which has been affected further by the further increase in electricity outages.

Amount of water across Gaza governorates

In liters per capita per day

Access to desalinated water

Water piped through the municipal network is used mostly for domestic purposes other than drinking and cooking as it has high salinity due to over-extraction from the Gaza aquifer, which is the only available source of natural water. Currently, less than 5 per cent of all water extracted from the Gaza aquifer meets internationally recognized drinking standards.

As a result, about 90 per cent of people in Gaza have little choice but to purchase desalinated water for drinking and cooking, primarily from private water providers. Apart from the fact that the quality of this water is questionable, the cost of one cubic metre of purchased water ranges from 30-50 NIS compared with 1-1.3 NIS for water supplied through the network. This increases the financial burdens faced by poor families.

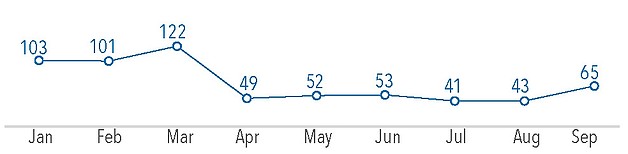

The deterioration in energy supplies since April has significantly reduced production in all Gaza desalination plants to only 55 per cent of maximum capacity of 20,000 cubic metres per day. As with piped water supplies, desalinated plants increased production moderately during September, but it remained at nearly half the level recorded in March 2017, prior to the start of the current crisis.

Volume of desalinated water produced by month

In thousands of cubic metres

Wastewater treatment

A variety of factors, including the energy deficit and import restrictions imposed by Israel as part of the blockade, had already left wastewater treatment facilities unable to operate at full capacity. The additional power outages since April 2017 and subsequent challenges in synchronizing the operation of different components of the system, have further undermined the capacity of these facilities.

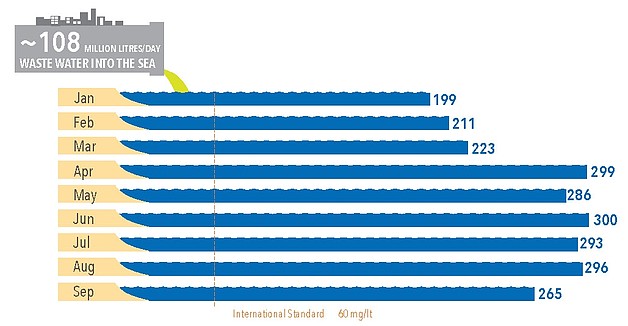

This has led to a decline in the quality of approximately 108 million litres of wastewater discharged every day into the Mediterranean Sea, with an increase in sea pollution and heightened health and environmental risks.

Pollution levels measured in September were 10 per cent lower than the monthly average between April and August, but remain higher than in the first three months of 2017, and over four times higher than the international environmental health standard.

Concern over waterborne diseases

The declining availability of water for drinking and other domestic purposes, both through the network or via desalination plants, has exacerbated health risks, particularly for poorer households. These include the risk of contracting waterborne diseases following consumption of polluted water and/or as a result of a decline in hygiene practices.

Diarrhea among children under three is a common indicator of poor water consumption. The number of documented cases has increased significantly since April 2017 and peaked at over 4,200 cases in July. The number of cases fell to around 4,000 in August and 3,300 in September. The decline can be attributed to the ongoing distribution of emergency fuel, combined with the decline in demand with the end of the summer season.

Pollution levels of wastewater flows into the sea

(in mg/litre of bod*)

"We have no choice but buying expensive desalinated water"

Mona, mother of seven, Rafah

Forty-four-year-old Mona lives with her husband and seven children in the Orabia neighbourhood of Rafah city. Most families in the area rely on agriculture-related work, paid primarily by the hour, including Mona’s husband. Mona is a housewife caring for Sama, four years old, and Sara almost two, plus five additional school-age siblings.

Forty-four-year-old Mona lives with her husband and seven children in the Orabia neighbourhood of Rafah city. Most families in the area rely on agriculture-related work, paid primarily by the hour, including Mona’s husband. Mona is a housewife caring for Sama, four years old, and Sara almost two, plus five additional school-age siblings.

Mona’s husband earns 20 NIS per day, most of which is used for the family’s daily meal, commonly comprising vegetables and grains, with milk for the youngest children. “Often, my husband and I choose not to eat to save food for our children. Sometimes I substitute milk with tea when I don’t have enough money.” Buying medicine when the children fall ill is a separate struggle.

Since April, the family has received three hours of electricity per day rather than six hours as supplied previously. Unlike most of the neighbouring homes, Mona’s house is connected to the water network and should be supplied with piped water twice a week for a few hours. “In practice, we never receive water that often”, said Mona. “Due to the low pressure, water does not reach the water tanks on the roof and requires an electrical pump, but the supply of water and electricity rarely coincide.”

As most other families in the area, Mona purchases water from a nearby private agricultural well. This is five times more expensive than water provided by the municipality and lacks any form of safety or quality control. After the children contracted giardia worm and diarrhea, both waterborne diseases, Mona began to buy desalinated water from a private vendor. To buy 60 litres per day at 3 NIS per litre, this is nearly 50 times more expensive than water from the network and consumes 15 per cent of the family’s income. “I don’t believe this water is very clean either but it is the only option”, said Mona.

* This section was contributed by WASH Sector partner, Oxfam.

[1] Unless otherwise indicated, all WASH-related figures are provided by UNICEF on behalf of the WASH cluster.

[2] It is estimated that leakages in the network account for the loss of 33% of the water produced at source before it reaches homes.