2015 Overview: Forced displacement

In this section

-

oPt overview

-

Latest developments: January-April 2016

-

Main trends in the Gaza Strip

-

Main trends in the West Bank

oPt Overview

“The creation of new facts on the ground through demolitions and settlement building raises questions about whether Israel’s ultimate goal is, in fact, to drive Palestinians out of certain parts of the West Bank, thereby undermining any prospect of transition to a viable Palestinian state.”

UN Secretary-General’s remarks to the Security Council on the situation in the Middle East, 18 April 2016

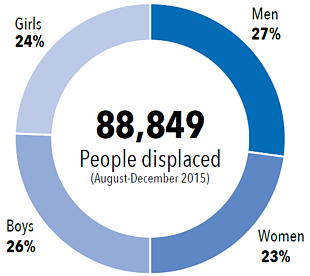

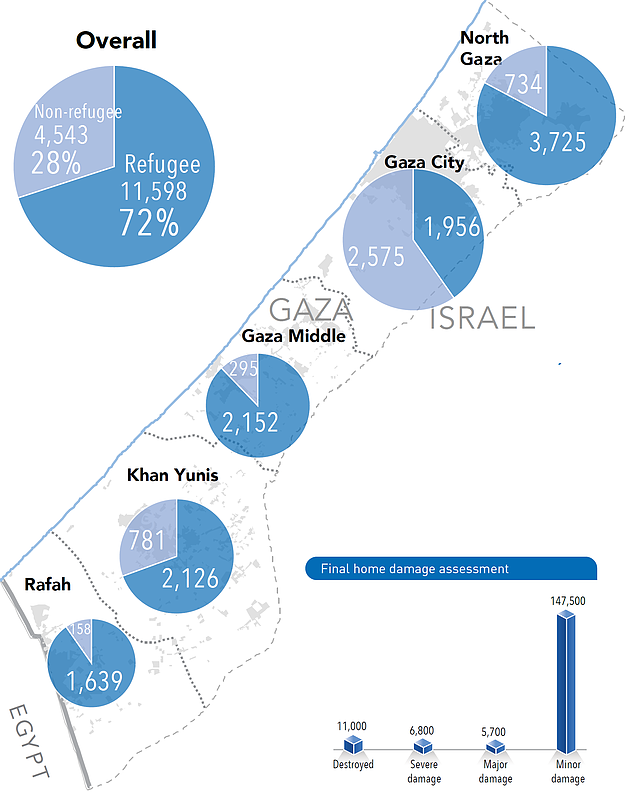

The forced displacement and dispossession of Palestinians across the oPt takes place in the context of Israel’s prolonged occupation and lack of respect for international law, compounded by recurrent rounds of hostilities in the Gaza Strip. Although no major displacement occurred in Gaza in 2015, internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the Gaza Strip continue to suffer from the devastating consequences of the 2014 hostilities between Israel and Palestinian armed groups, including Hamas, with an estimated 90,000 people still displaced during the second half of 2015.

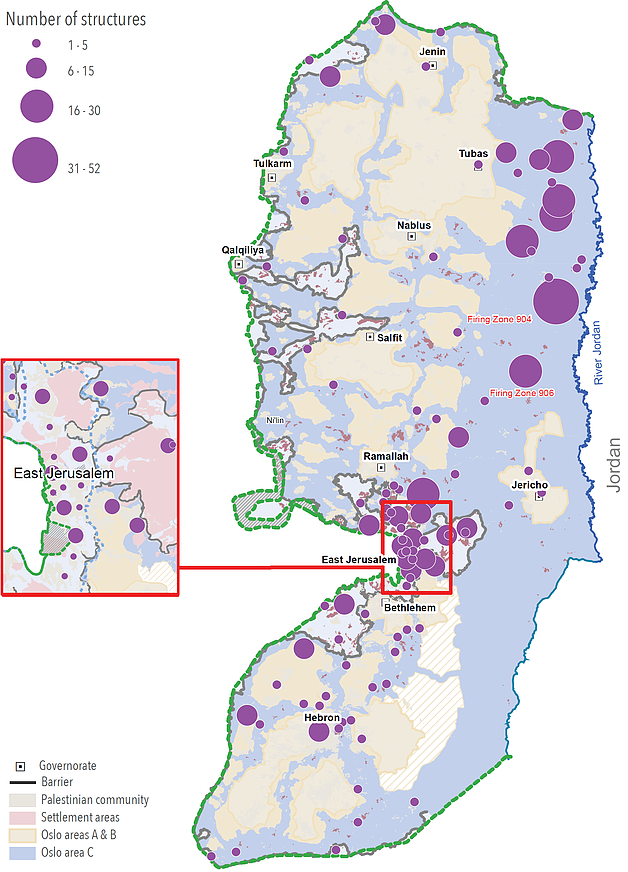

Israeli policies and practices in certain parts of the West Bank, particularly in Area C and East Jerusalem, have contributed to the creation of a coercive environment that undermines a Palestinian physical presence and exacerbates the risk of individual and mass forcible transfers. The planning system applied in Area C favours Israeli settlement interests over the needs of the protected population and makes it almost impossible for Palestinians to obtain building permits: between 2010 and 2014, Palestinians submitted 2,020 applications for building permits in Area C, of which 33 were approved.[1] A similarly restrictive planning regime in East Jerusalem has resulted in only 13 per cent of the municipal area zoned for Palestinian construction, most of which is already built up.

Latest developments: January-April 2016

- The number of Palestinian structures demolished, or dismantled and confiscated by the Israeli authorities across the West Bank sharply increased in the first four months of 2016, surpassing the figures for all of 2015 (598 vs. 548). Overall, 858 Palestinians, around half of them children (416), were displaced, compared to 787 people in the whole 2015. As in 2015, the vast majority of demolitions took place in small herding communities in Area C, exacerbating the risk of forcible transfer. Punitive demolitions also continued during 2016 with 12 homes targeted (included in the above total), alongside the advancement of legislation that would allow the punitive expulsion of families of suspected perpetrators of attacks from the West Bank to the Gaza Strip.

- In the Gaza Strip, the reconstruction and repair of homes destroyed and damaged during the 2014 hostilities continued during the first quarter of 2016. Between 3 April and 22 May, Israel suspended the entry of cement to Gaza for the private sector, following a diversion of cement from its legitimate beneficiaries, as well as the discovery of a tunnel running under Gaza to Israel. This delayed the reconstruction and repair of homes of IDPs.

Main trends in forced displacement

Gaza Strip

Obstacles to reconstruction

Obstacles on the entry into Gaza of the enormous amounts of construction materials needed for the repair and reconstruction of homes has been a major challenge. Since October 2014, the Israeli authorities have facilitated the entry of construction materials for the repair of damaged homes under the “shelter repair stream” of the Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism (GRM). The introduction of the “residential stream” of the GRM in July 2015 resulted in a significant increase in the number of trucks entering Gaza, enabling beneficiaries to access materials both for the reconstruction of homes that were completely destroyed and for new housing. However, due to ongoing Israeli restrictions, the slow pace of disbursement of pledges made by member states for reconstruction, and the inability of the Palestinian Government of National Consensus to assume effective government functions in Gaza, progress on reconstruction has been slow for IDPs. By the end of the 2015, 15 per cent of displaced families (2,700) were able to return to homes that had been repaired or reconstructed.

Obstacles on the entry into Gaza of the enormous amounts of construction materials needed for the repair and reconstruction of homes has been a major challenge. Since October 2014, the Israeli authorities have facilitated the entry of construction materials for the repair of damaged homes under the “shelter repair stream” of the Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism (GRM). The introduction of the “residential stream” of the GRM in July 2015 resulted in a significant increase in the number of trucks entering Gaza, enabling beneficiaries to access materials both for the reconstruction of homes that were completely destroyed and for new housing. However, due to ongoing Israeli restrictions, the slow pace of disbursement of pledges made by member states for reconstruction, and the inability of the Palestinian Government of National Consensus to assume effective government functions in Gaza, progress on reconstruction has been slow for IDPs. By the end of the 2015, 15 per cent of displaced families (2,700) were able to return to homes that had been repaired or reconstructed.

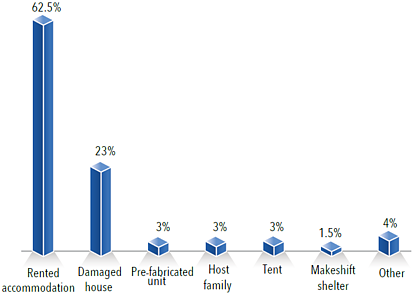

Displaced girls and women

The living conditions of displaced girls and women, accommodated with host families, in rented apartments, prefabricated units, tents and makeshift shelters, or in the rubble of their previous homes, raise a range of protection concerns, including lack of privacy and increasing exposure to gender-based violence. The traditional retention of property rights by men, including rights over homes destroyed or damaged during the war, impedes the access of displaced women to legal and shelter-related assistance.

The living conditions of displaced girls and women, accommodated with host families, in rented apartments, prefabricated units, tents and makeshift shelters, or in the rubble of their previous homes, raise a range of protection concerns, including lack of privacy and increasing exposure to gender-based violence. The traditional retention of property rights by men, including rights over homes destroyed or damaged during the war, impedes the access of displaced women to legal and shelter-related assistance.

IDP Households (as of the second half of 2015)

West Bank, including East Jerusalem

Forced displacement in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, is triggered by multiple factors, including building restrictions; the destruction of homes and livelihoods for lack of Israeli-issued building permits or on punitive grounds; conducting military training exercises near residential areas; forced evictions; settler violence; revocation of residency; restrictions on access to services and livelihoods; relocation plans; or any combination of these factors.

Demolitions in the West Bank

Demolitions due to lack of permit

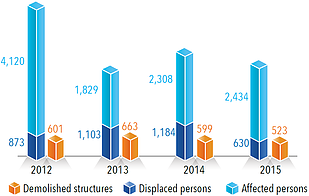

Area C and East Jerusalem remains a serious concern. According to the Israeli authorities, these demolitions are a legitimate law enforcement measure against structures built without the required permit. The number of such structures demolished and people displaced in this context decreased by 13 and 48 per cent compared to 2014. However, tens of thousands of Palestinians endure fear and insecurity due to outstanding demolition orders, with an estimated 13,000 structures, including homes, facing pending demolition orders in Area C.[2] Due to the current discriminatory and unlawful planning processes it is almost impossible for Palestinians to obtain building permits in the vast majority of in Area C and East Jerusalem.[3]

Area C and East Jerusalem remains a serious concern. According to the Israeli authorities, these demolitions are a legitimate law enforcement measure against structures built without the required permit. The number of such structures demolished and people displaced in this context decreased by 13 and 48 per cent compared to 2014. However, tens of thousands of Palestinians endure fear and insecurity due to outstanding demolition orders, with an estimated 13,000 structures, including homes, facing pending demolition orders in Area C.[2] Due to the current discriminatory and unlawful planning processes it is almost impossible for Palestinians to obtain building permits in the vast majority of in Area C and East Jerusalem.[3]

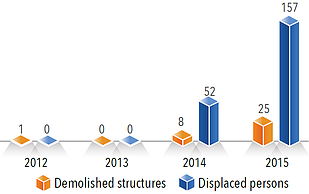

Punitive demolitions/sealing off

The Israeli authorities resumed this practice in mid-2014, after an almost complete halt for the previous nine years, and expanded its application since October 2015, citing the need to deter potential Palestinian attackers. During 2015, the Israeli authorities demolished or sealed on punitive grounds 25 residential structures, displacing 157 Palestinians, including 74 children. This practice targets the family homes of suspected perpetrators of attacks against Israelis (including those killed during the attacks), and therefore constitute collective punishment;[4] in several cases, apartments adjacent to those targeted have also been destroyed or severely damaged and their residents displaced (included in the total).

The Israeli authorities resumed this practice in mid-2014, after an almost complete halt for the previous nine years, and expanded its application since October 2015, citing the need to deter potential Palestinian attackers. During 2015, the Israeli authorities demolished or sealed on punitive grounds 25 residential structures, displacing 157 Palestinians, including 74 children. This practice targets the family homes of suspected perpetrators of attacks against Israelis (including those killed during the attacks), and therefore constitute collective punishment;[4] in several cases, apartments adjacent to those targeted have also been destroyed or severely damaged and their residents displaced (included in the total).

Military training exercises

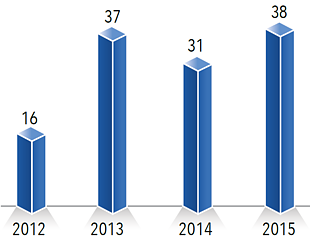

The temporary displacement of entire communities located in areas designated as “firing zones” in the context of military exercises has become systematic in recent years. Despite the entry prohibition by military order, there are at least 38 herding communities with over 6,200 residents currently located in these “firing zones”, which cover approximately 18 per cent of the West Bank.[5] Many of these communities were present in these areas prior to them being designated as closed during the 1970s.

The temporary displacement of entire communities located in areas designated as “firing zones” in the context of military exercises has become systematic in recent years. Despite the entry prohibition by military order, there are at least 38 herding communities with over 6,200 residents currently located in these “firing zones”, which cover approximately 18 per cent of the West Bank.[5] Many of these communities were present in these areas prior to them being designated as closed during the 1970s.

Herding communities at risk of forcible transfer

Most Bedouin and herding communities across Area C (total population estimated at 30,000) are at risk of forcible transfer due to a coercive environment, which includes: the destruction and threat of destruction of homes, schools and animal shelters, due to lack of building permits; restrictions on access to grazing land; lack of basic infrastructure; and intimidation and attacks by Israeli settlers. In some areas the Israeli authorities have advanced explicit plans to remove the communities from their current locations.

-

Central West Bank

Israeli plans foresee the “relocation” of 46 Bedouin communities (around 7,000 Palestinians) in the central West Bank to three sites, which are at various planning stages: Al Jabal (Jerusalem), Fasayil and An Nwei’meh (Jericho). Some of these communities are currently located in and around strategic areas earmarked for Israeli settlement infrastructure, including the planned E1 settlement project.[6]

-

Southern West Bank

The Israeli authorities have sought to transfer around 1,200 Palestinians from eight herding communities in southern Hebron (Masafer Yatta), on the grounds that the area is designated as “firing zone 918”. Most affected families have been living in the area from before this designation. A “mediation” process between the Israeli authorities and the communities’ legal representatives ended without a resolution by the end of 2015. Some portions of the “firing zone” are planned for settlement expansion.[7]

Settler takeover

In 2015, following the implementation of eviction orders, Israeli settlers took over three houses in East Jerusalem, displacing seven Palestinians including four children. Israeli law allows Israeli individuals and organizations to pursue claims to land and property they owned in East Jerusalem prior to the establishment of the State of Israel, while most Palestinians are unable to do the same regarding land and property in what is now Israel.

Endnotes

[1] Response dated 16 November 2014 from Lieut. Eliran Sason of the Civil Administration to a request under the Freedom of Information Act submitted by Adv. Sharon Karni-Cohen of Bimkom.

[2] From mid-August to December 2015, the IDP Working Group carried out a survey targeting households who lost their homes during the 2014 hostilities. For a summary of the main findings see: OCHA, Gaza: Internally displaced persons, April 2016.

[3] Report of the Secretary-General on “Israeli settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and in the Occupied Syrian Golan,” A/HRC/31/43, 20 January 2016, para. 69. See also OCHA, “Under Threat: Demolition Orders in Area C of the West Bank,” September 2015.

[4] Humanitarian Coordinator calls for end to punitive demolitions in the occupied West Bank, Press release, 16 November 2015.

[5] A recent research indicates that nearly 80 per cent of “firing zones” are not used for training. See: Kerem Navot, A Locked Garden, March 2015.

[6] The authorities have justified the plan claiming that the residents lack title over the land and that the relocation will improve their living conditions. The residents, however, have not been genuinely consulted about the plan; they firmly oppose this plan and insist on their right to return to their original homes and lands in southern Israel. In the meantime, they have requested protection and assistance in their current location, including adequate planning and permits for their homes and livelihoods.

[7] In 2012 the Israeli Civil Administration (the “Blue Line Team”) endorsed the declaration of “state land” within Firing Zone 918, allocated to the settlements of Yattir, Susiya, Abigail and Ma’on. See Kerem Navot, A Locked Garden, p. 83.