Seawater pollution raises concerns of waterborne diseases and environmental hazards in the Gaza Strip

This article was contributed by Oxfam with support from the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Cluster

The immense electricity deficit affecting the Gaza Strip, alongside the longstanding shortage of adequate sanitation infrastructure, continues to result in the discharge of 100-108 million litres of poorly treated sewage into the sea every day.[1] This situation poses serious health and environmental hazards, particularly during the summer when swimming in the sea is one of the few recreational activities available to the population of Gaza. According to WHO, water-related diseases account for over one quarter of illnesses and are the primary cause of child morbidity in the Gaza Strip.[2] The current operation of wastewater treatment plants may be undermined further in the near future due to the funding gaps facing the UN programme of emergency fuel to run backup generators at critical facilities, as well as the recent tightening of the blockade.

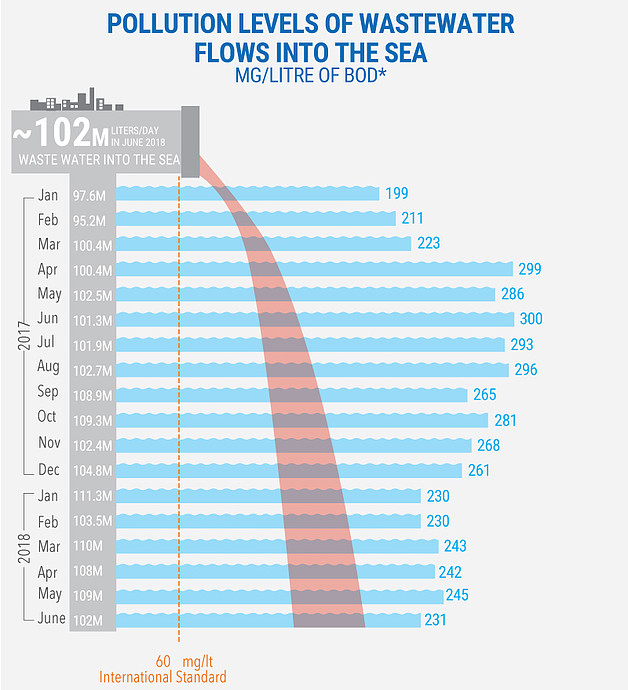

The pollution levels of the wastewater discharged into the Mediterranean during the first half of 2018 declined by some 20 per cent compared with the April-December 2017 period, attributable primarily to increased emergency fuel support to the relevant facilities. However, current pollution levels remain nearly four times higher than the international environmental health standard (see chart).[3]

The indicator used to measure pollution (Biological Oxygen Demand) reflects the presence of pathogenic and non-pathogenic microbes derived from sewage, sewage effluent, industrial processes, farming activity and wildlife, and which can thrive in the human body and lead to disease.[4] Children, the elderly and people with weak immune systems are the most likely to develop illnesses or infections after coming into contact with polluted water.

The indicator used to measure pollution (Biological Oxygen Demand) reflects the presence of pathogenic and non-pathogenic microbes derived from sewage, sewage effluent, industrial processes, farming activity and wildlife, and which can thrive in the human body and lead to disease.[4] Children, the elderly and people with weak immune systems are the most likely to develop illnesses or infections after coming into contact with polluted water.

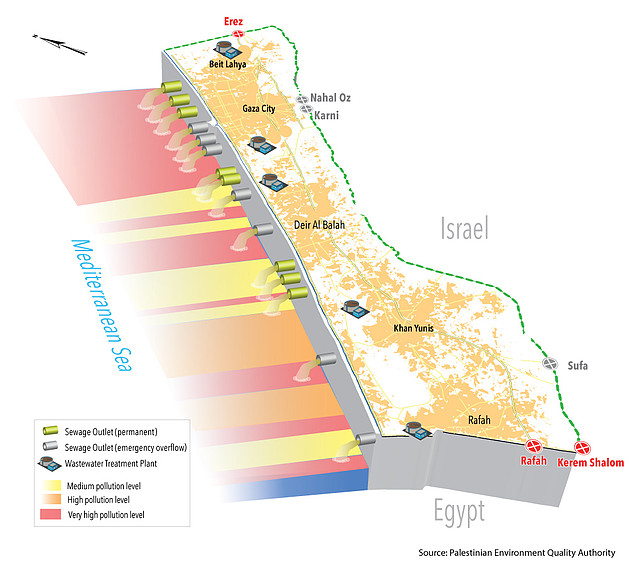

The Environmental Quality Authority in Gaza declared the beaches of Gaza City, the main destination for internal tourism, and in Rafah governorates, as highly polluted. These beaches constitute 75 per cent of all Gaza beaches and swimming in these areas is strongly discouraged.[5]

The electricity shortage is the main cause undermining the provision of water, sanitation and hygiene services. Since April 2017, following a deterioration in the intra-Palestinian political divide, Gaza has been supplied with only 4-5 hours of electricity a day, down from 8-12 hours previously. Over 85 per cent of the electricity currently available is purchased from Israel; the remainder is produced locally by the Gaza Power Plant (GPP), but only one of its four turbines is in operation due to lack of funds to purchase fuel. Supplies from Egypt have largely come to a halt in 2018 because of failure to repair feeder lines.

Treatment plants: overloaded, under-powered and poorly maintained

Until recently, there were four wastewater treatment plants in the Gaza Strip. Some of these have dealt with volumes of sewage well beyond their planned capacity. For example, the Wadi Gaza plant in the Middle Governorate was designed to process up to 14,000 cubic meters of sewage a day but currently receives some 17,000 cubic meters. Due to the huge electricity deficit, these plants rely heavily on back-up generators run on fuel to operate at a limited capacity. Poor maintenance due to funding shortages, and the shortage of spare parts that are prevented or delayed entrance under the blockade, have also undermined operations. Up to 23 essential WASH items are classified by Israel as “dual-use”; while these items can be imported via the Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism, the process is long and difficult.[6]

As a result, poorly treated wastewater from substandard plants is discharged directly into the sea every day, causing extensive contamination of the beaches. The precarious nature of these facilities also generates a constant threat of sewage flooding in areas adjacent to reservoirs and pumping stations. This threat materialized on 4 May 2016, when one of the retention walls of a sewage lagoon in Gaza City’s treatment plant (Sheikh Ejleen) collapsed following a prolonged power cut, releasing 15,000 cubic meters of raw sewage into a nearby farming area.

In April 2018, a new large and modern plant (North Gaza Emergency Sewage Treatment), which has been under construction for about a decade, came into operation with a maximum capacity of 35,600 cubic meters per day. Unlike the other plants, it benefits from a dedicated electricity line from Israel, allowing it to operate almost continuously. The treated wastewater, which meets international standards, is recharged into the aquifer rather than discharged into the sea.[7]

Emergency fuel

Supported by donors, the UN has been coordinating the delivery of emergency fuel to run back-up generators in the Gaza Strip since 2013. This has ensured that a minimal level of lifesaving health, water and sanitation services are maintained despite the severe energy crisis. The number of critical facilities requiring fuel support has increased from 189 in April 2017 to 249 at present, including the four sewage treatment plants and related pumping stations.

The list of selected facilities is revised on a monthly basis by the relevant clusters and the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) on the basis of the availability of electricity, and changing needs and priorities. To enable stakeholders to trace and analyze the evolution of the electricity supply and the emergency fuel programme, and to identify gaps easily, OCHA developed a dynamic, user-friendly dashboard, available online.

The emergency fuel mechanism faces a severe funding shortage and unless new funding is urgently provided, distributions may halt by mid August, risking a sharp reduction or even a collapse of the supported facilities. Of the WASH facilities relying on emergency fuel, wastewater treatment plants are likely to be the first affected because water wells and water pumps used for water supply are usually prioritized. An additional $4.5 million are urgently required to ensure that distributions continue through to the end of 2018. On 17 July 2018 Israel banned the entry of fuel and cooking gas, items used in power-starved Gaza to compensate for the chronic lack of electricity. On 24 July 2018, the partial entry of fuel and gas to Gaza was permitted. [8]

“I can’t prevent my children swimming in the sea”

Summer comes with the promise of bathing away the heat and humidity by swimming, and spending long nights sipping coffee and chatting at the beach. The Gaza beach has become more than an escape from summer heat and also provides a means to cope with the long hours of electricity cuts. Families relaxing and children running around is a common sight along Gaza’s coast throughout summer but this activity is increasingly under threat from rising pollution of the sea. Swimming pools can provide a healthier alternative but they are few in number and are not affordable for the majority of families.

For Ahlam Sharaf, a 38-year-old mother with eight children aged between 12 and three years of age, the sea is part of her life and that of her children. They live in a small house in Deir al Balah camp, right next to the Mediterranean. With few supported recreational opportunities in the area, playing at the beach is the children’s first option, especially during the summer holiday. “I can’t prevent the children from going there,” said Ahlam. “They love to swim and spend their time at the beach. We have been neighbours with the sea for many years.”

She explained how the wastewater pipe located near the beach discharges wastewater on a daily basis, turning the colour of the sea dark black. She believes that her children suffer from many skin diseases as a result of swimming in the sea. For the children, the beach is essential and denying them the option to swim is beyond discussion. As Ahlam’s son, 11-year-old Ismail said: “I am just in love with the sea.” Ahlam’s husband suffers from ill health and works as a cleaner for few days a month, making around 10-15 ILS per day. Their desperate economic situation does not allow Ahlam’s family to afford the use of private swimming pools and the sea is the only option for the children to escape long summer days.

[1] OCHA. United Nation-Assisted Emergency Fuel Distributions, 2013-2014. June 2018.

[2] Report of a field assessment of health conditions in the oPt. WHO. February 2016.

[5] Environmental Quality Authority. April 2016.

[7] Prior to the launching of the new plant, sewage collected in northern Gaza was discharged in a number of lagoons.