The humanitarian impact of de facto settlement expansion: the case of Asfar

New research to enhance humanitarian response and preparedness

Since 1967, about 250 Israeli settlements and settlement outposts have been established across the occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem. This violates Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention which prohibits the transfer by the occupying power of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.[10]

Some settlement practices, including many of those highlighted here, also violate domestic Israeli legislation.

The establishment and continuous expansion of settlements is a key driver of humanitarian vulnerability. It deprives Palestinians of their property and sources of livelihood, restricts their access to services, and creates a range of protection threats that, in turn, have triggered demand for assistance and protection measures from the humanitarian community.[11]

Research and monitoring of settlement expansion has mostly focused on the construction of residential areas and has neglected, to some extent, other forms of expansion. These include the development of road networks, agriculture and touristic sites, mostly on privately-owned Palestinian land, without formal permit from, but with the acquiescence of, the Israeli authorities (hereafter: defacto expansion). Although settlement-related issues such as settler violence and access restrictions to protect settlements are regularly monitored, their relationship to the phenomenon of settlement expansion is often overlooked.

To enhance the humanitarian community’s understanding of these patterns and its ability to respond, OCHA has collected and analysed data on various affected areas in the West Bank.[12] The following case study of Asfar settlement in Hebron governorate is the first in a series of Humanitarian Bulletin articles presenting the findings of this research.

The case of Asfar

Asfar (also known as Metzad) was established in 1983 as a military outpost (“nahal”) on privately-owned and cultivated Palestinian land, which was requisitioned under a military order citing ‘security needs’.[13] A year later, the army handed the outpost over to an Ultra-Orthodox Jewish group for the establishment of a civilian settlement. Nearly 600 Israeli settlers currently live in Asfar and its nearby outpost.

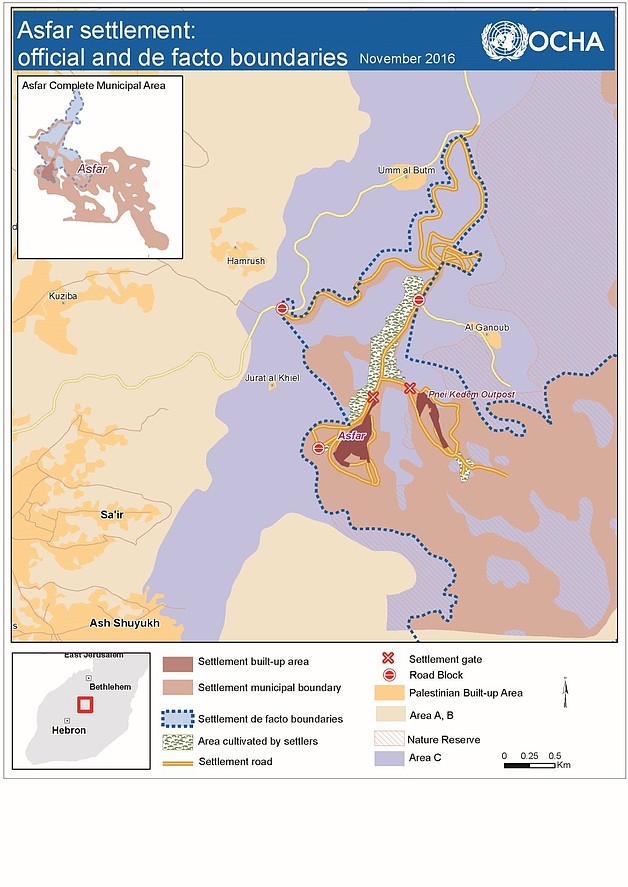

Soon after Asfar’s establishment, the authorities transferred thousands of dunums of land previously declared as ‘state land’ to the Asfar municipal boundaries, now comprising nearly 7,800 dunums.[14] This is more than 50 times the size of the current built-up area (about 150 dunums).

Due to its hilly topography and size, settlers have not made use or otherwise established a presence over most of this huge municipal area. Instead, they have expanded their control over the more accessible areas in the immediate vicinity of the residential core, outside the municipal boundaries, including more than 2,300 dunums of land, nearly half of which, owned primarily by Palestinians, according to official Israeli records.[15] The establishment and gradual expansion of the settlement has had a severe impact on specific Palestinian landowners, on the general population of two adjacent towns, Sai’r and Ash-Shuyukh (over 33,000 people), and on two small herding and farming communities: Al Ganoub and Jurat Al Kheil (approx. 200 people).

Expansion of a permanent settler presence

In 1992, without the building permits or official authorization required from the Israeli authorities, Asfar settlers established a residential outpost (Asfar B) on a nearby hilltop, partially located on the land previously requisitioned for ‘security needs’. The outpost was gradually abandoned in subsequent years. In 2000, it was repopulated by a different group of settlers and was renamed Pnei Kedem. By early 2015, the Israeli authorities had issued 60 demolition orders against most of the structures erected in the outpost; none of these demolition orders have been enforced.[16]

Settlers have begun to cultivate olive trees and vines on more than 300 dunums of mostly privately-owned Palestinian land. These ‘farming activities’ benefit from the financial support of the Settlement Division of the World Zionist Organization, a body whose budget is entirely funded by the Israeli government.[17]

The de-facto expansion of the settlement has been facilitated by the development of an extensive road network, largely banned for Palestinian use. Extending over some 18 kilometres, this network includes two connections to the main road leading northwards (to Jerusalem), and a series of internal dirt roads connecting the various sections of the settlement-controlled area to each other. All of the dirt roads (8 kilometres) encroach onto private Palestinian land and were built without permits.

Discouraging Palestinian access

In a series of group discussions conducted by OCHA, residents of the affected Palestinian communities reported that the regular presence of armed settlers in the area has played a critical role in intimidating and discouraging them from accessing their land in the settlement-controlled area. This intimidation comes primarily from the security coordinators and guards of the settlement and outpost. These coordinators have been officially granted policing powers, such as carrying weapons and detaining suspects.[18]

Soldiers stationed in a military base within the settlement-controlled area are responsible for staffing the access points and supporting the security coordinators.

The intimidation has been fueled by sporadic attacks against farmers and their property over the years. In the group discussions, people indicated that the intensity of attacks peaked during the second Intifada (2000-2005), but detailed documentation is not available for this period. Since 2006 when OCHA began documenting settler violence, 18 attacks resulting in Palestinian injuries (five incidents) or property damage (13 incidents) have been recorded around Asfar. This figure excludes the more frequent incidents of harassment, access prevention, or the expulsion of farmers and herders from their land.

In at least seven of the incidents resulting in casualties or damage, complaints were filed with the Israeli police, but no suspects in any case have been indicted.

Palestinian access is impeded by physical and administrative means. Part of the main road leading to the settlement, which previously linked the Al Ganoub herding community to Sa’ir town, has been entirely closed to Palestinian use since the beginning of the second Intifada (September 2000) on security grounds, although no written order was issued to that effect. Additionally, in 2005 the army installed a roadblock on another key road running next to the settlement (Wadi Sai’r road), effectively preventing Palestinian use.

These restrictions, jointly enforced by the army and the settlement security forces, have contributed to reducing the Palestinian presence and facilitating the takeover of land.

Despite all the impediments and risks, and following repeated unsuccessful attempts, members of one Palestinian family (see case below) managed in April 2016 to gain access to part of its land within the settlement-controlled area and planted a few hundred saplings.

The entire municipal area of Asfar is declared ‘closed military area’, making it off-limits for Palestinian use. This classification applies to the municipal areas of all settlements (excluding those in East Jerusalem).[19]

Shrinking space, reduced livelihoods and risk of forcible displacement

The practices highlighted above have had a pervasive impact on the Palestinian communities surrounding Asfar. In Al Ganoub and Jurat Al Kheil, both located in Area C, these practices, combined with the discriminatory planning processes, have created a coercive environment that pressurizes people to leave.

The Israeli authorities fail to provide these communities with any sort of planning and residents are unable to obtain building permits. In four incidents during the past year alone (November 2015-October 2016), the authorities demolished or requisitioned 28 homes and livelihood-related structures in the two communities, including four structures previously provided as humanitarian aid. Lack of planning also prevents either community from connecting to the water or electricity networks, rendering residents dependent on expensive water tankering (up to ten times the price of piped water) and unreliable solar panels to meet their basic needs. Settler attacks and intimidation compound the water shortage, limit access to traditional grazing areas and severely undermine the community’s main sources of livelihood.

Vehicular access from Al Ganoub to its main service center in Sa’ir is dependent on access to the road leading to Asfar. Between 2000 and 2007, this road was permanently blocked.

It was closed again between December 2015 and January 2016. When the junction is blocked, the road can only be accessed on foot or by donkey, from where alternative transportation can then be sought.

For Sai’r and Ash-Shuyukh, the main impact is the loss of potential income from farming activities. Statistics on land cultivation outside built-up areas in Hebron governorate show an estimated 8,000 dunums of cultivable land within the official and de facto area of Asfar. Cultivation of this area by Palestinians, based on irrigation, variety of crop and the rate of return in the rest of the governorate, would generate an output of approximately $ 2.1 million a year.[20] This is a conservative estimate based on existing limited levels of irrigation and excluding other significant income-generation activities such as herding.

Both villages face a fragile socio-economic situation:

- Unemployment is estimated by the Sai’r and Ash-Shuyukh village councils at 20-25 per cent, above the 19 per cent for Hebron as a whole;

- 350 families (approx. 1,700 people) are classified as ‘hardship cases’, and are entitled to cash assistance from the Palestinian Ministry of Social Development (MoSD);[21]

- 749 households (approx. 3,700 individuals) not covered by the MoSD are dependent on food assistance (food rations or vouchers) provided by UNRWA and the UN World Food Programme (WFP).

The restoration of full access and security for Palestinians to their land in the settlementcontrolled areas would generate much-needed livelihood and employment opportunities, alleviating the hardship of families affected by unemployment and food insecurity. This would also generate an economic ‘spillover effect’ with the additional income spent on local goods and services, multiplying the impact of the initial growth.

The case of the Abu Shanab family

Ahmad Abu Shanab (53), from Sa’ir, together with his ten brothers and six sisters, inherited 320 dunums of land within the area now controlled by Asfar. In the 1970s, the family planted fruit trees (almonds, peaches and apricots) which, together with seasonal crops (tomatoes, beans, corn, wheat and barley), became the main source of income for 12 nuclear families.

Access constraints began soon after the establishment of Asfar in 1983, but the situation deteriorated dramatically following the second Intifada in 2000, when an armed settler started to prevent access to the area.

“The last time I tried to reach the land in 2000, I was physically assaulted and badly injured by a group of armed settlers, who also damaged my car. I thought I was going to die. Later, I filed a complaint with the Israeli police but never heard back”, Mr Abu Shanab said. The loss of income from the farming and grazing activities had a significant impact on the living conditions of the expanded family. “Some food items that were previously produced in-house, including some seasonal vegetables and fruits, as well as meat, milk and eggs, became more infrequent on our table,” Mr Abu Shanab said.

In September 2014, following nearly a decade and a half of lack of access, the Abu Shanab family planted 1,800 olive saplings and 500 almond trees on part of their land within the settlement-controlled area, at a total cost of some NIS 20,000 (approx. US $5,300). An Israeli human rights organization representing the family informed the Israeli authorities in advance of the planting activities. However, all the saplings and trees were uprooted by settlers in three separate incidents between February and May 2015. Complaints filed with the Israeli police after these attacks have not led to the indictment of perpetrators. In February 2016, the family made an additional attempt and planted 800 saplings that have remained in situ and have been tended a number of times without impediment.

[10] This has been confirmed numerous times, among others, by the International Court of Justice (Advisory Opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory of 9 July 2004); the High Contracting Parties to the Fourth Geneva Convention (Declaration of 5 December 2001); the United Nations Security Council (Resolution 471); and the United Nations General Assembly (Resolutions 3092 (XXVIII), 47/172 and 66/225).

[11] For an overview of the humanitarian responses to settlement activities proposed by humanitarian agencies operating in the occupied Palestinian territory for 2016, see the Humanitarian Country Team, Strategic Response Plan 2016, available here.

[12] Cases were selected to represent different geographical areas across the West Bank and the extent to which settlement activities in each of the pre-selected cases has received attention from humanitarian actors.

[13] Requisition order 8/83. The residential area of Asfar was established contrary to common practice as this order does not contain an expiration date and has apparently never been renewed.

[14] Military Order 783 Regarding Regional Councils – Asfar, 21 January 1998. The size of the municipal area referred to in the text excludes a large section (over 4,000 dunums) which was turned into Area A following the issuance of the order and is no longer part of the settlement, although the order itself was not updated.

[15] Calculation based on a GIS layer obtained from the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA) marking the status of the land in the affected area as either privately-owned or public (also known as ‘state’) land.

[16] GIS layer provided by the ICA to Dror Etkes following an information request under the Freedom of Information Act.

[17] http://www.pneikedem.org/81938/ חקלאות . This page was recently removed and is no longer available.

[18] While the IDF is formally responsible for arming, training and supervising the settlement security coordinators, the coordinators are also accountable to the municipal bodies of the settlement that appoint them and pay their salaries, often creating a conflict of interests. For further background on the issue see: Yesh Din, The Lawless Zone, June 2014.

[19] See: Declaration regarding the Closure of an Area [Israeli Localities] [Judea and Samaria] 2002, of 6 June 2002.

[20] The economic potential of agriculture was estimated by FAO based on data provided by OCHA on the size of the areas affected and on cultivation patterns in Nablus governorate provided by PCBS (2007/8).

[21] Payments range from NIS 750-1,800 every three months depending on the severity of the case.