Restricted livelihoods: Gaza fishermen

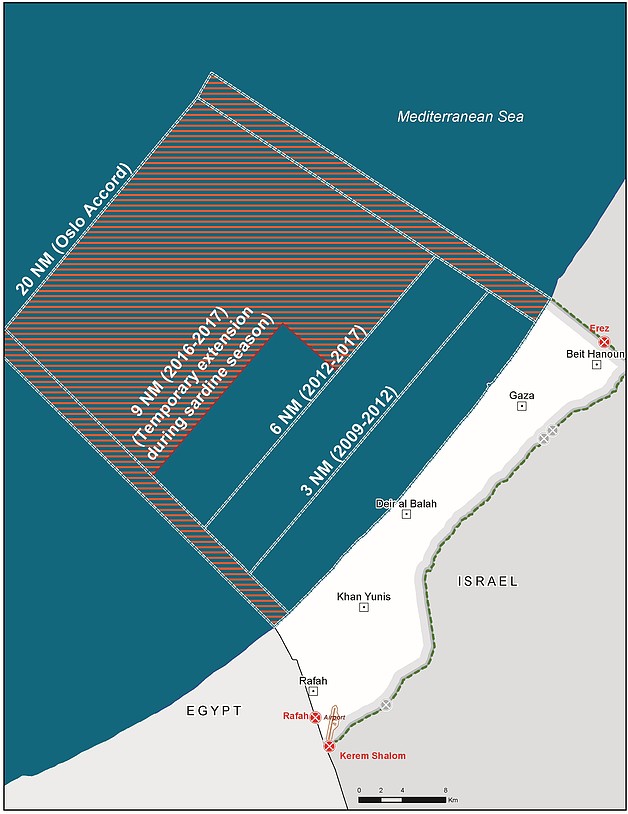

Since September 2000, Israel has tightened restrictions on Palestinian access to the sea, citing security concerns. These restrictions have been enforced through the firing of live ammunition, arrests and the confiscation of equipment. While sea restrictions have varied, since 2006 fishermen have generally been allowed to access less than one third of the fishing areas allocated to them under the Oslo Accords: six out of 20 nautical miles (NM), although this has temporarily been extended to nine NM during the sardine season in recent years.

Fish, particularly sardines, is a major source of protein, micronutrients and essential Omega 3 fatty acids for Palestinians in Gaza and contributes to nutritional diversity. The fish available in the six NM area tend to be smaller in size. Israel and Egypt also impose a “no fishing zone” along their respective maritime boundaries with Gaza. Over 35,000 Palestinians still depend on this industry for their livelihoods.

Abdallah al ‘Abasi from Ash Shati Refugee Camp, Gaza

July 2013: “Fishing seemed a prosperous business”

Abdallah al ‘Abasi, a 53-year-old fisherman from Ash Shati refugee camp in the northern Gaza Strip, operates a boat with four of his seven sons and another 12 fishermen. The income generated by Abdallah’s boat provides for about 70 people, the majority of them children. For many years, Abdallah was employed as a construction worker in Israel. In September 2000, following the beginning of the second Intifada, the loss of his job in Israel pushed him to seek an alternative livelihood.

“Fishing seemed a prosperous business. I bought a small 7 metre-long-boat and began to work day and night. We were able to reach very far into the sea. At the beginning, I used to make about US$1,000 a month, which at that time was quite a lot, so I managed to save some money and buy a double-sized boat and three smaller boats. We sold the fish to the local market and to merchants from the West Bank and Israel.”

Following Operation Cast Lead in January 2009, the fishing area was reduced to three nautical miles (NM). “From that time our financial situation began to deteriorate rapidly. The fishing catch was only a fraction of what it used to be, both in quantity and in quality. We lost access to the bigger and more valuable fish. The best income we were able to make then was $ 45 per day versus over $ 70 previously. On some days, we had no income as we were not even able to cover the cost of fuel. We had to cut our expenses, even on the basic things.”

Published in July 2013 Gaza’s Fishermen Case Study

May 2017: “As if the sea turned to asphalt”

Abdallah, now aged 57, still operates a fishing boat which is the only source of income for about 80 people. He goes fishing almost every day during the two fishing seasons.

“We simply do not know what will happen to us. Things are just getting worse, be it the fish catch, the blockade, or the [Israeli] persecution and shootings at sea. The fishing zone where fishing is permitted is barren. Despite the recent expansion from six to nine NM, the area is sandy and overfished, as if the sea turned to asphalt. The fish are in rocky areas or in areas deep in the sea beyond the 9 NM limit. This is where fish spawn and are most productive. Access to these areas is prohibited and I even fear getting closer to the shooting zone. The Israeli navy does not hesitate to shoot. In Arabic we say “This is a meal which does not need spoons”, i.e. it is not worth taking the risk.

Now is the peak of the sardine season, but there are hardly any, as if fish is extinct. The fish we catch is very small and not profitable. It’s very discouraging. All the hard work we do does not pay off. We barely cover the cost of the fuel for the boat. If any of the fishing equipment gets damaged, we cannot afford to fix it.

Before the blockade, the income generated in the few months of the two fishing seasons used to be enough for the entire year. You could see the smile on the fishermen’s faces. Nowadays we hardly reach 10 per cent of what we used to make. We come back from fishing angry and frustrated. All we want to do is shout. The bleak situation has affected us badly. We cannot meet our children’s needs. Whoever thought he would be able to marry his son or daughter off or build an extension to his house has to put the plans on hold. If we had other options, we’d have long left the business… but this is Gaza for you: no job opportunities. If we were not patient, we would have been long gone. We have to be hopeful.”