Reconstruction of homes destroyed during hostilities yet to begin

Lack of funds pledged in donor conference main impediment

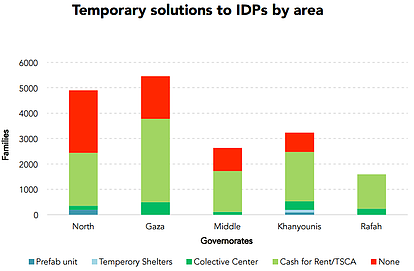

The situation of the approximately 100,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) as a result of the July-August hostilities remains precarious and uncertain. Approximately 8,800 of them currently reside in 14 UNRWA Collective Centres, 1,700 in prefabricated housing units, and the rest in rented accommodation, with host families or in makeshift shelters in the rubble of their damaged or destroyed homes.

In order to assist the largest number of people in the shortest possible time, shelter actors have prioritized cash assistance for rent, supporting IDPs with homes destroyed or severely damaged, and cash assistance for repairs, for those whose houses sustained partial damage.

In order to assist the largest number of people in the shortest possible time, shelter actors have prioritized cash assistance for rent, supporting IDPs with homes destroyed or severely damaged, and cash assistance for repairs, for those whose houses sustained partial damage.

The full reconstruction of homes is a highly complex endeavour, which requires various planning stages, including entire neighbourhoods and their related infrastructure, and is extremely costly. Therefore, the bulk of this caseload is to be addressed through reconstruction projects implemented by UN agencies and governmental bodies, with only a small portion being “self help” projects, where individuals carry out the reconstruction.

However, due to the slow pace of disbursement of pledges made by donors during the Cairo Conference in October 2014, compounded by delays in the assessment and clearance of projects through the temporary Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism (GRM), as of the end of February 2015 only two housing projects were approved and none has started on the ground. The GRM allows for the controlled entry of building materials designated by the Israeli authorities as “dual use items” (mainly cement, gravel and metal bars).[1]

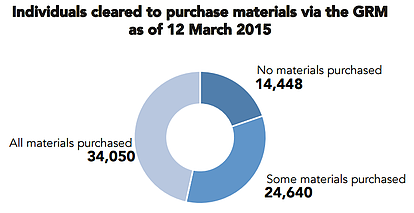

Of the approximately 58,000 individuals (usually one individual per family) who have purchased restricted building materials (cement, gravel and metal bars) through the GRM, virtually none are IDPs whose homes were destroyed or severely damaged. The latter are among the nearly 14,500 cases who have been cleared by the GRM, but have not yet purchased any materials. Of those that have accessed building materials through the GRM, less than 60 per cent have purchased the full quantity of materials allocated to them in the damage assessments, while the rest bought only part of their respective allocations, presumably due to the lack of financial resources.

The lack of visible progress and uncertainty regarding a durable solution for the IDPs is prolonging the hardship of affected families and adding to the general frustration in the population caused by the longstanding movement restrictions, the salary crisis and the lack of employment opportunities.[2]

Rubble removal

A critical precondition to the start of reconstruction is the removal of rubble from the targeted sites. UNDP estimates that around two million tons of rubble were generated during the summer’s hostilities, three times more than during the Cast Lead offensive in 2008-9.

The Palestinian Ministry of Public Works and Housing is overseeing and coordinating rubble removal activities within Gaza by a range of actors, including UNDP. The latter aims to remove and sort approximately one million tons of rubble over a period of two years, half of which, will be crushed and reused for road construction projects.

Once complete, the removal of rubble will enable more than one million people in affected areas to access basic services, particularly through the reconnection of households to water and sanitation infrastructure, and will reduce the risk of collapsing buildings and the threat of explosive remnants of war (ERW).

As of early March 2015, UNDP had removed 95,000 tons of rubble, or nearly ten per cent of its final target, and transferred it to crushing sites. Rubble removal has been made possible with funding from Sweden, Japan and USAID. However, a funding gap of nearly $8 million remains for the crushing and reuse of rubble.

Transitional shelter cash assistance

Transitional shelter cash assistance (TSCA) is being provided to families whose homes were severely damaged or totally destroyed based on damage assessments carried out by UNRWA for the refugee population, and UNDP and the Ministry of Public Works and Housing (MPWH) for the non-refugee population.

Due to a critical shortage of funds, on 27 January 2015, UNRWA was forced to partially suspend its cash assistance programme supporting repairs and rental subsidies. However, through reallocation of existing funds and savings, supplemented by the receipt of pledges, since then UNRWA has distributed cash to some 12,600 families for a total of $ 16.5 million. Germany, together with Saudi Arabia are the key donors to UNRWA’s shelter cash assistance program in Gaza. UNRWA continues to face a $ 545 million shortfall to support refugee families with minor damage to repair their homes and to continue the provision of TSCA.

As of early March, UNDP had provided TSCA to a total of 2,633 non-refugee families with severely or totally damaged housing units for a period of up to six months, slightly more than half the total number of families found eligible (4,994). UNDP’s vulnerability criteria for prioritizing families for assistance were IDPs residing in UNRWA shelters, female-headed households and large-size families. Funding for TSCA is limited and 74 per cent of the overall needs remain unfunded;more than $23.2 million still needed to cover TSCA for non-refugee families and $1.8 million for refugeefamilies.

Protection strategy

A strategy was developed by humanitarian partners to guide the work of humanitarian actors in protecting the human rights of IDPs for the duration of their displacement. This strategywas subsequently endorsed by the Humanitarian Country Team. The key priorities identified in the strategy include:

- Profiling and tracking of IDPs: To ensure an appropriate and targeted response.[3]

- Regular and systematic monitoring of the protection situation of IDPs: Many IDPs have suffered either physical or psychological harm as a result of the conflict and continue to live in overcrowded conditions that offer little privacy. The resulting stress has increased tensions within families and communities, reflected in domestic violence, legal concerns associated with inheritance rights, guardianship rights, and girls and women being at risk of early or forced marriage.

- Targeting humanitarian response based on need: While all displaced households require assistance, some families and individuals are more vulnerable than others. It is imperative that those who are most vulnerable or who have special needs are prioritized. Particularly vulnerable groups include women; children; households where the main breadwinner is disabled or whose livelihood was affected; persons who are elderly or frail; and persons at risk of exposure to ERWs.

- Access to legal support: UN agencies and civil society organizations who monitor protection and document human rights violations should provide advice on accessing appropriate legal support, on legal documents and pursuing justice mechanisms for accountability and compensation for losses.

IDP girls and women – a highly vulnerable group

A study carried out by UN Gender Based Violence sub-working group and led by UNFPA immediately after the ceasefire of August 2014,[4] illustrates how the conflict has had a deep impact on women and girls. Increased cases of violence have been reported against them in emergency shelters, host family situations and other places of refuge. Women were subjected to many types and varying degrees of violence and often responded with silence or by directing violence towards their children, especially girls. Some girls and women also reported discrimination in receipt of aid and services in emergency shelters or with host families.

The following are illustrative quotes from women who participated in focus group discussions during the study:

(...) “My father-in-law was beating me and humiliating me during the war. Sometimes, I was driven away from their home to the street. Nobody supported me.”

“I slept in my jilbab (gown). There was only one toilet in the home where we sheltered. I was ashamed to enter the toilet in the presence of my brothers-in-law, so I waited until they went out.”

“I do not inform anybody about my problems and keep them to myself. This is because I have one brother who is ill and I fear that he may die if he knows I am not well. Also I cannot tell my husband what my brothers-in-law and father-in-law do to me because he is also ill. I don’t want to increase his concerns; he is a cancer patient.”

“I have lost my home, I have lost everything”

Masa’ad Attallah Abu Gaddaieen, from Beit Lahia, 46, is currently unemployed, but years of hard work in the agricultural sector enabled him to save some money that he invested in the construction of his home.

“In Gaza you are not safe at home. My family and I have been displaced twice in two years. The first time was during the Israeli military operation in November 2012, and the second time as a result of the recent conflict.”

In July 2014, the Israeli army began massive bombardment of the area where the family home is located, but they stayed at home for ten days despite the bombardments. When the Israeli military ground operation began, the family left their home and took shelter in one of the UNRWA schools. The situation inside the shelter was very difficult and conditions were crowded.

“We managed to visit our home during the temporary ceasefire 25 days into the hostilities. We found our home and around 95 other homes in the area completely destroyed by Israeli bulldozers. We were shocked and helpless; it was all gone, everything we had struggled to build. I have worked all my life to have a house of my own, and then the Israeli bulldozers came and destroyed it in seconds.”

After the end of the hostilities, Masa’ad and his family had to relocate to another UNRWA shelter in Al Remal area, where they stayed for 15 days before moving to a shelter in Beach camp, where some of the family still live.

“The long stay and situation inside the shelter has become a great strain on my family and I have no money to rent an apartment. The economic situation is very difficult. We erected a makeshift shelter from plastic and fabric near our destroyed home.” Currently, some members of the family feel more comfortable staying in the makeshift shelter despite the winter season and the exposure to harsh weather conditions.

“We are waiting for UNRWA assistance to be able to rent an apartment temporarily, but we have heard that UNRWA has no money to help us. All I hope for is that our home will be reconstructed very soon so we can return to a life of dignity.”

[1] For further details on the GRM see OCHA Humanitarian Bulletin, December 2014.

[2] For an overview of the impacts of the ongoing salary crisis, see OCHA Humanitarian Bulletin, January 2015.

[3] For more information, see OCHA Humanitarian Bulletin, January 2015 (p. 9).

[4] See: UNFPA, Protection in the Windward, October 2014.