Gaza’s Energy Crisis

For the past decade, the Gaza Strip has suffered from a chronic electricity deficit that has undermined its already fragile living conditions. The functioning of Gaza’s sole power plant (GPP) is impaired by disputes between the Palestinian authorities in Gaza and Ramallah over the funding and taxation of fuel; the inadequate collection of bills from consumers; the destruction of fuel storage tanks by an Israeli strike in July 2014; and Israeli restrictions on imports of spare parts and equipment, citing security concerns. In April 2017 the GPP shut down completely after exhausting its fuel reserves. It resumed partial operations in late June with fuel purchased from Egypt. Gaza also relies on the purchase of electricity from Israel and Egypt.

In May 2017, the Ramallah-based Palestinian government decided to cut its payments for electricity provided to Gaza by Israel. As a result, Israel reduced its supply by 40 per cent in late June. In recent years, the electricity deficit has required a rationing system entailing regular rolling blackouts of 12-16 hours per day, occasionally increasing to up to 22 hours. This has had a direct impact on the delivery of services, including health, water and sanitation, and education. To prevent the collapse of essential services, the UN is coordinating the distribution of emergency fuel to 186 critical facilities.

Abeer Al Nemnem from Ash Shati Refugee Camp, Gaza

April 2014: “Shortage of cooking gas is every mother’s nightmare”

Abeer al Nemnem, aged 41, lives with her husband and their 11 children in a three-bedroom house with no windows and one little kitchen in Ash Shati refugee camp (Beach camp) in Gaza. Her husband is ill and unemployed. She works in a kindergarten for NIS300 a month. Abeer struggles to provide decent hot meals for her large family. Her everyday life is exacerbated by Gaza’s chronic energy crisis. Shortages of cooking gas and regular electricity cuts make it impossible to carry out the most basic activities such as providing tea or warm milk for her children in the morning.

“Shortage of cooking gas is every mother’s nightmare. If we run out of gas, we have to wait for more than three weeks to get our gas cylinder refilled. We cannot afford a backup cylinder as we are very poor. I sometimes use a small gas cylinder…When the small cylinder runs out, I try to time food preparation with the electricity cuts schedule, using an unsafe electric stove to prepare simple meals such as fried potatoes, eggs or hot milk for the children. The stove is not safe because of the poor electricity supply and because it is low on the ground. I’m always afraid one of the children will knock it over and burn themselves. It often happens that the children wake up at night during electricity cuts and I cannot even prepare milk for them. It’s even worse when my children have to go to school without breakfast or even a cup of milk or tea…My children are exposed to danger every time we run out of gas, but what can I do?”

Since 2013, 64 people have been injured and at least 26 people, half of them children, have been killed in Gaza in accidents linked to the electricity crisis.

Case published in April 2014 Humanitarian Bulletin

June - 2017 “Supplies of running water and electricity rarely coincide”

Since April, Gaza has been plunged into almost constant darkness after the shutdown of Gaza’s sole power plant.

“How can I run a household without cooking gas, electricity and water?!,” said Abeer when revisited in June 2017. “It’s catastrophic. It’s now been two months without gas. The (private) gas supplier said our turn for refilling has not come yet. I have a little gas cylinder but this can barely heat food and I use it just for emergencies. I can only cook when we have electricity but this is unpredictable and lasts just for two or three hours maximum. I don’t know when we will have electricity but I must tailor my time around it. It drives me crazy!

Today, for example, my children told me that the electricity would be back at 6 in the evening. If that is true, it will give me just enough time to cook a meal before Iftar – breaking the daily Ramadan fast. The other day, we only had electricity around midnight. I had no choice but to make bread as we had run out and I needed bread for the children. Making bread at night is very challenging because the only space I have is the living room where my children sleep. I had to move the sleeping children to my room while I baked. By the time I finished it was just before dawn. When we have electricity during the day I can either cook or make bread, never the two together. I cannot even use a washing machine, as the power supply is weak. I do all the washing by hand.

My daughter is sitting for her final high school exams and she cannot study. We have only two emergency lights, which are not strong enough for reading. I don’t let her use a candle because it is unsafe. I’d rather live in darkness than risk my children’s lives.

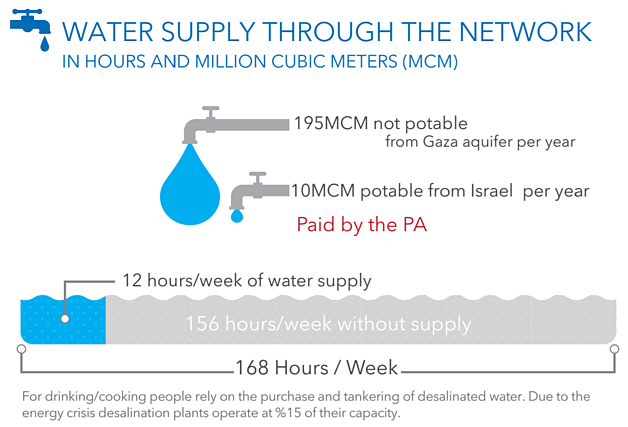

Blackouts also mean that the water pump is not working and there is no running water to take a shower. Supplies of running water and electricity rarely coincide. When there is electricity there is no water and when there is water there is no electricity. We have running water every other day, sometimes only every three days, and then only for only a few hours a day. The water is very salty and cannot be used for drinking or cooking, only for cleaning the house and taking showers. Showering in salty water hurts my eyes and damages my daughters’ hair. For drinking we refill containers of water from the mosque desalination station, which offers it for free, but it is not always available because the desalination machine is dependent on electricity.

I feel so sorry for my children. There is nothing for them to do and there is no space for them to play. When I was their age, we never had blackouts. We used to play in the streets and were happy. Now the streets are dark. As time passes I feel things are getting worse. We live under blockade. Gaza is a prison where one is shackled and cannot do anything.”