First exports from Gaza to Israel since 2007

Transfers to the West Bank also increase. Although welcome, developments have had little immediate impact on Gaza economy still struggling to recover from the July-August hostilities.

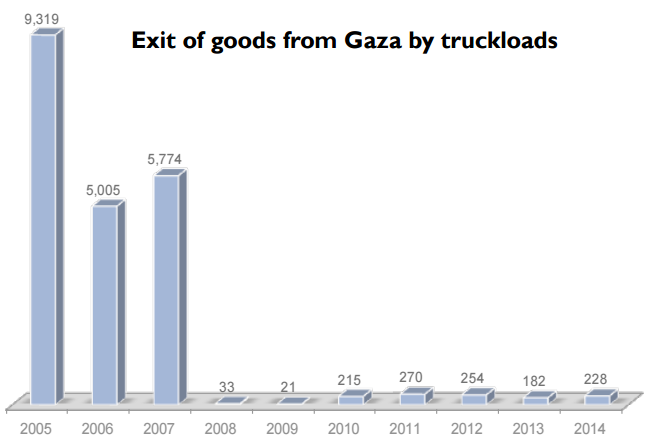

In March the first exports took place of agricultural products from the Gaza Strip to Israel since the imposition of the blockade in June 2007.[1] This follows on from the partial resumption of commercial transfers of agricultural produce,[2] furniture and garments from Gaza to the West Bank in November 2014, when Israel relaxed restrictions in the wake of the ceasefire ending the July-August 2014 hostilities. In the first quarter of 2015, some 234 truckloads of agricultural produce, furniture and garments exited Gaza for Israeli, international and West Bank markets, already exceeding the 228 truckloads recorded during the whole of 2014.

In March the first exports took place of agricultural products from the Gaza Strip to Israel since the imposition of the blockade in June 2007.[1] This follows on from the partial resumption of commercial transfers of agricultural produce,[2] furniture and garments from Gaza to the West Bank in November 2014, when Israel relaxed restrictions in the wake of the ceasefire ending the July-August 2014 hostilities. In the first quarter of 2015, some 234 truckloads of agricultural produce, furniture and garments exited Gaza for Israeli, international and West Bank markets, already exceeding the 228 truckloads recorded during the whole of 2014.

Although a positive development, this represents only a fraction of the over 5,700 truckloads of a wider range of exports that left Gaza to Israel, the West Bank and the external world in the first half of 2007 prior to the imposition of the blockade.

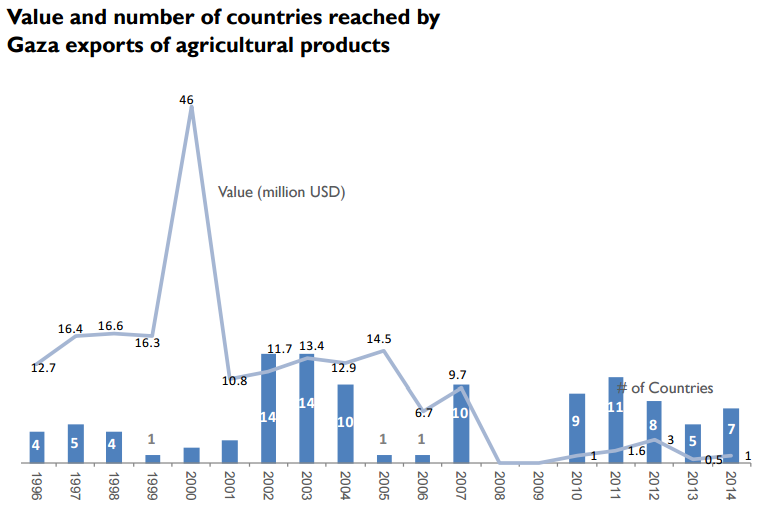

Agricultural exports have traditionally played an important role in the Gaza economy, averaging $15.6 million annually from 1996 to 2007. Approximately 77 per cent of exports were to Israel. Prior to June 2007, 90 per cent of garments, 76 per cent of furniture and 20 per cent of food products were marketed outside Gaza, primarily exported to Israel or transferred to the West Bank. In 2005, the furniture sector in Gaza employed more than 5,500 workers and generated US$55 million in sales, almost 50 per cent of this derived from exports to Israel and abroad or transfers to the West Bank. Until 2007, the textile sector employed 25,000 workers, mostly women.[3]

Following the Hamas takeover of Gaza in June 2007, Israel prohibited exports from Gaza to its markets[4] and severely restricted transfers to the West Bank. Israel did permit limited exports from Gaza to third countries to pass through its territory and a minimal quantity of cash crops were exported from Gaza to Europe as part of an agreement with the Dutch government. The first non-agricultural exports to the outside world were not permitted until 2012 – consisting of one sample truckload each of furniture and garments. The first transfers from Gaza to the West Bank also resumed in 2012 – locally-produced date bars for a World Food Programme school-feeding programme – with approximately 60 truckloads in total for 2012 and 2013.

These minimal exits of goods did little to invigorate the debilitated export sector in Gaza, in which the annual value of agricultural exports averaged only US$1.2 million from 2010 to 2014. The share of manufacturing and agricultural sectors in Gaza’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) declined from 21 per cent and 10 per cent in 1994 to just 10 per cent and six per cent respectively by 2013, ‘in part by the collapse of exports in the wake of the restrictions on the movement of goods and people.’[5] In the years after 2007, Gaza became largely dependent on the illegal smuggling tunnel network under the border with Egypt, which supplied almost all commodities, including until mid-2013, most of the construction materials to the construction sector, one of the few functioning outlets in the depressed economy, which employed about 24,000 people, approximately 10 per cent of the workforce.

The resumption of exports to Israel in March coincides with the seven-year Shmita cycle when agricultural land in Israel should lie fallow according to Jewish tradition, and exports from Gaza to Israel traditionally increase to cater for the religiously observant population. So far, agricultural exports to Israel have been restricted to tomatoes and eggplants; 16 truckloads worth approximately US$150,000 were exported in March. The current quota for exports from Gaza to Israel is a maximum of 250 tonnes of tomatoes and 55 tonnes of eggplants per week, although a wider variety of vegetables is expected to be approved soon.

Israel has also approved imports of the other mainstays of the Gaza export economy: furniture and garments. According to the Office of the Quartet Representative, whose officials have held meetings in recent months with Israeli buyers, Gaza manufacturers and the Manufacturers Association of Israel, both sides are positive about the resumption of trade relations, even after almost eight years of interruption. However, progress is currently stalled over a disagreement on Value Added Tax (VAT) invoice requirements for furniture and garment exports to Israel; agriculture is exempt from VAT, hence the ongoing exports of tomatoes and eggplants to Israel. To compound the problems, Israeli coordination officials recently informed their Palestinian counterparts that wooden planks thicker than five centimetres and wider than 20 to 25 centimetres are prohibited from entering Gaza for the private sector until further notice, reportedly due to their use by armed groups for tunnel building.[6]

The resumption of furniture and garment exports to Israel will depend on the re-training of staff and rebuilding of machinery. The impact on the Gaza economy as a whole will probably be very limited taking into account the major shocks suffered in recent years, the destruction of the illegal smuggling tunnel network under the border with Egypt since mid-2013, and the enormous destruction resulting from the July-August hostilities in 2014. Over 30,000 jobs were lost in the Gaza construction sector in the first half of 2014 following the destruction of the tunnels and the longstanding restrictions on the import of construction materials; overall unemployment in Gaza stood at 42.8 per cent at the end of 2014.[7] As a result of the July-August hostilities, GDP in Gaza fell by 28.4 per cent from the second quarter of 2014 and by 31.8 per cent year on year.[8]

According to traders and farmers in Gaza, a number of immediate measures could be taken by the Israel authorities, specifically for agricultural exports and transfers, which would have a significant impact on the Gaza economy:

- Allow trade to the West Bank through additional crossings and on all working days, as opposed to the current rota of Sundays, Tuesdays and Thursdays;

- Increase the height of expert cargo loads to 1.6 metres as a step towards the international standard of 1.9 metres;

- Reduce the waiting time and provide shaded areas at crossings;

- Reduce the number of pallets per trader that need to be security-checked;

- Allow the use of containers in Kerem Shalom;

- Apply the same regulations for goods destined for the West Bank as those applied for exports to the EU.

In addition, the lifting of restrictions on both the variety and volume of exports to Israel to respond to the extra demand of the Shmita year could have a positive effect on the Gaza economy and farming livelihoods. It would improve the terms of trade for farmers in Gaza and encourage them to plant larger areas for this market. It would also minimize the adverse impact on consumers in the West Bank, since increased exports to Israel lead to a rise in prices for locally produced produce which would be balanced by Gaza production. Ultimately, however, the economy in Gaza will only recover through the full lifting of the blockade and the free movement of people and goods.

Easing of access restrictions on Palestinian West Bank ID holders

On 12 March, the Israeli authorities announced that entry for men and women holding West Bank ID cards and aged over 55 and 50 respectively, would be allowed without a permit into East Jerusalem and Israel on a daily basis via Israeli-controlled checkpoints after 08:00. The length of time for which they may stay in East Jerusalem and Israel was not specified. This measure came into effect a few days after its announcement.

Based on population figures published by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, around seven per cent of the male population of the West Bank (98,865 out of 1.44 million) and 11 per cent of females (159,344 out of 1.39 million) fall within this age group.

While this is certainly a positive development, at present it is difficult to assess its precise impact on the social, economic and health conditions of Palestinians. OCHA conducted interviews with pedestrians of the relevant age group crossing into East Jerusalem through the two main checkpoints of Qalandiya and Gilo. As per the new announcement, West Bank ID holders in this age group only had to present their ID cards to cross, although two women aged around 60 were denied access in two separate incidents for reasons that were unclear to them.

The bulk of the interviewees reported that they were going to attend prayers at Al Aqsa Mosque. Some of them indicated that they had not been able to pray there since last Ramadan, or for longer periods, as they had been obliged to apply for a permit. One couple, aged around 60, at Qalandiya was keen to visit the Al Aqsa mosque for the first time in ten years.

Other interviewees indicated that they were seeking health treatment. In two separate interviews, two patients, a man aged 59 and a woman aged 65, revealed that they were going for treatment in East Jerusalem hospitals for the first time in years. Another man aged over 60 said he was crossing the checkpoint for the first time in a number of years to obtain medicine from an East Jerusalem hospital for his sick son.

In two cases, individuals holding permits were not asked to show it at the Gilo checkpoint: a woman aged 51 holding a work permit, who said she hopes to avoid the lengthy procedure of applying for a permit in future, and an elderly Christian couple who had been granted permits to visit their families in East Jerusalem during the Easter holidays prior to the new announcement.

How can I compete in West Bank markets?

My name is Mujahed Al Sousy and I am the general manager of the Sousy Furniture Company in Jabalia, north Gaza. Our company used to export our products to the Israeli and West Bank markets. Before the blockade in 2007, around 150 skilled labourers worked in our company and we exported between 25 and 30 truckloads each month.

The blockade restricted our products to Gaza markets, which can absorb only five per cent of our output and requires only 25 workers in the summer season and 15 in winter. In November 2014, Israel allowed us to transfer goods to the West Bank for the first time since 2007. But the 40-50 truckloads we have transferred since then are still low compared to 25-30 truckloads per month in the past.

We face other challenges in transferring furniture. Our shipments must be palletized to only one metre in height and there are steep logistical costs because of all the loading and offloading for security. Another problem is that we are not allowed to be at the crossing ourselves. Now, we are shocked that Israel is banning the entry of wooden planks wider than five centimetres and higher than 25 centimetres. How can I compete in West Bank markets with all of these additional costs and problems?

* The UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) contributed to this report

[1] According to the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT) this represents a ‘pilot’ programme that may be expanded in the near future.

[2] This included vegetables, strawberries, dates and fish. The transfer of strawberries was halted by Israel in January 2015 when some strawberries were found to have been smuggled into Israeli markets from the West Bank.

[3] Gisha – Legal Center for Freedom of Movement: A Costly Divide: Economic Repercussions of Separating Gaza and the West Bank, February 2015, pp.16-17.

[4] From June 2007 until the resumption of exports to Israel in March 2015, the only exceptions were three truckloads of palm fronds exported to Israel for the Jewish Sukkot holidays.

[5] Palestinian Economic Bulletin: Special Issue December 2014: Gaza’s Reconstruction.

[6] Information conveyed by Gisha.

[7] The Portland Trust, Palestinian Economic Bulletin, February 2015. Construction-related employment accounted for seven per cent of employment in the third quarter (Q3) of 2013, but fell to just 1.3 per cent in Q3 2014 and rebounded only marginally to 1.8 per cent in Q4 2014.

[8] Ibid.