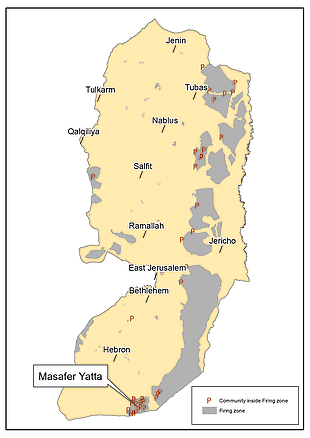

Firing zones and risk of forcible transfer

Since the 1970s, Israel has declared some 18 per cent of the West Bank, or nearly 30 per cent of Area C, as firing zones for military training. A presence in these zones is prohibited by military order unless special permission is granted. Despite this prohibition, there are 38 small Palestinian herding communities with a population of over 6,200 located within these zones. Many of these communities existed in the area prior to its closure.

These Palestinians are among the most vulnerable in the West Bank with high levels of humanitarian need. Most have faced the demolition of their homes and sources of livelihood on the grounds of lack of building permits, which are impossible to obtain. Some have been repeatedly displaced for short periods of time to make room for military training. These and related practices have generated a coercive environment, placing the affected people at risk of forcible transfer.

Khaled Al ‘Amoor from Khirbet Sarura – Masafer Yatta, Hebron

May 2013: “Settlers set our crops alight and killed my donkey”

Khaled al ‘Amoor [7] was born in 1958 in the herding community of Khirbet Sarura in the Masafer Yatta area of south Hebron. Khalid and his four siblings own 200 dunums of land in Sarura, where they grew wheat, barley and other seasonal vegetables for domestic consumption. According to Khaled, about 24 families lived in Sarura before 1967. These were herding and farming families living off their livestock and land.

In the 1980s, the Israeli authorities designated most of Masafer Yatta, where 14 herding communities live, as a closed military zone for training: “Firing Zone 918”. Since then, these communities have been subjected to a range of policies and practices by the Israeli authorities and Israeli settlers that have undermined their living conditions. Khirbet Sarura was particularly affected and gradually depopulated as a result.

“I was born in Khirbet Sarura and have lived there for more than 30 years. I got married and my wife delivered 10 children there. I left in 1996 with other families when the road to our village was closed by settlers from the nearby Ma’on settlement, but I continued to access my land in the area for several years. However we continued to experience violent attacks by settlers; in 2003 for example, the settlers attacked us while we were harvesting our wheat – they set our crops alight and killed my donkey. …I had 120 heads of animals which I sold after I left Khirbet Sarura. I had no house to live in so I built a small house in Ar Rifa’iyya; this was later demolished by the Israeli authorities because I did not have a permit to build it. My children’s houses in Ar Rifa’iyya also have demolition orders against them. The barn I built in Ar Rifa’iyya to house the five cows that are my new source of income also has a demolition order. I lost everything when I fled Khirbet Sarura.“

Case published in May 2013 in Life in “Firing Zone’: The Masafer Yatta Communities Case Study

May 2017: “We don’t suffer anymore from settler violence but are more isolated”

“I now divide my time between Ar Rifa’iyya and al Majaz, one of the Masafer Yatta communities within the firing zone,” Khaled told OCHA in May 2017. “For two years after being forced to leave Sarura, I tried to settle in Ar Rifa’iyya but could not. I am used to the herding lifestyle, and the house we moved to was too small for my large family. Eventually, I moved to al Majaz where I own about 100 dunums of land, but had to start from scratch. I had no housing for my family or for my 400 sheep. I had to build a few rooms for my family, a big water well and two animal shelters.

“I now divide my time between Ar Rifa’iyya and al Majaz, one of the Masafer Yatta communities within the firing zone,” Khaled told OCHA in May 2017. “For two years after being forced to leave Sarura, I tried to settle in Ar Rifa’iyya but could not. I am used to the herding lifestyle, and the house we moved to was too small for my large family. Eventually, I moved to al Majaz where I own about 100 dunums of land, but had to start from scratch. I had no housing for my family or for my 400 sheep. I had to build a few rooms for my family, a big water well and two animal shelters.

I applied for a building permit but it was rejected by the civil administration on the grounds that this is a firing zone. All the structures now have demolition orders. In the last court hearing, two weeks ago, the judge refused to give us an injunction, which would have meant more time to legalize the structures before they are demolished, but called the Civil Administration to reach an agreement with us.

To sustain our herding way of life we have no choice but to stay in al Majaz, despite all the problems. We tried to move back to Sarura but our caves had been destroyed and the water wells poisoned by the settlers. As al Majaz is more isolated, we do not suffer from settler violence but meeting basic needs is more expensive. Due to the poor roads, I have to pay up to 60 shekels per cubic meter of tankered water instead of 20 that I would pay in Sarura. The same applies to transportation. A return journey from al Majaz to Yatta, the closest town, would cost 300 shekels in a taxi, and you don’t always find taxi drivers who agree to do it.

Wherever we go, we are persecuted by the Israeli authorities and their planning regulations. They just want the land without the people. But we have no alternative. We don’t have permits to work in Israel. We are not craftsmen and do not have professions or higher education. Herding and farming is what we know. This is our way of life.”

[7] In the original case, Khaled al ‘Amoor was referred to by the pseudonym Mohammad.