Addressing food insecurity among herders in Area C of the West Bank

Food assistance enables communities to avoid negative coping mechanisms

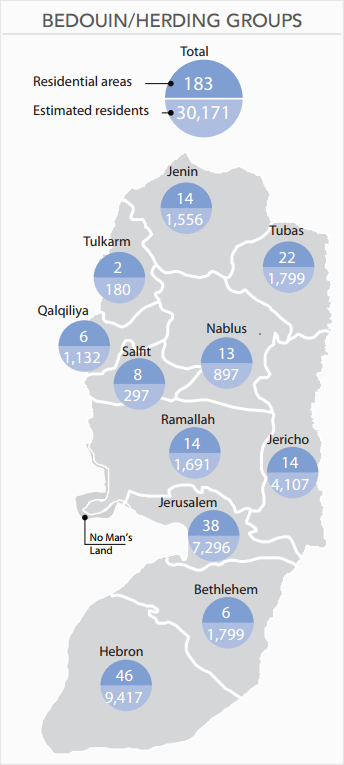

Since 2009, the UN World Food Programme (WFP) and UNRWA have provided regular food assistance to more than 30,000 Bedouin and other herders living in 183 residential areas across Area C of the West Bank.[1] These beneficiaries are amongst the poorest and most vulnerable Palestinians, with some communities seriously under threat of forcible transfer. The programme aims to ensure that their basic food needs are met and also contributes to building community resilience.

Food distributions take place every three months: WFP is in charge of food procurement and UNRWA of logistics. The food packages include staples such as fortified wheat flour, vegetable oil, and chickpeas or lentils. Both agencies jointly monitor and report on the programme, which is part of the 2015 Strategic Response Plan (SRP) for the oPt through the Food Security Sector.[2] In 2014 and 2015, this programme was made possible thanks to multilateral donors and with the support of Canada, Japan, Belgium and Switzerland.

Communities at risk of forcible displacement

Various Israeli practices affecting Bedouin communities in Area C have created a coercive environment that undermines food security and acts as a “push factor”. These practices include restrictions on access to grazing land and markets; denial of access to basic infrastructure; rejection of applications for building permits; and demolition or threat of demolition to homes, schools and animal shelters. Inthe first half of 2015 the Israeli authorities demolished 159 structures located in 15 herding communities across Area C on the grounds of lack of building permits; these demolitions constituted nearly two-thirds of all Area C demolitions during this period.[3]

In early July 2015, one of the affected communities, Abu Nwar, received demolition and stop work orders targeting dozens of their residential and livelihood structures. On a visit to the community, Israeli officials told the residents to vacate their homes by the end of the Muslim Eid al Fitr feast and move to the Al Jabal relocation site in advance of forthcoming demolitions.

Bedouin and herders in dozens of communities in southern Hebron also face a coercive environment that generates displacement threats. In July the Israeli authorities announced the imminent demolition of part of the community of Susiya on the grounds of lack of building permits.[5] Following concerns raised by multiple member states and other stakeholders, the demolitions and forcible displacement have not been executed to date.

A second community, Um al Kheir (26 families), faces constant challenges in accessing water. In addition, construction within the community is prohibited due to the lack of a planning scheme, and traditional herding and farming livelihoods are becoming increasingly unviable. These circumstances have severely undermined access to adequate quantities of good quality food.

Aziz, a 29-year-old engineer from Um al Kheir, said that he started to sell his sheep a few years ago as a way to survive. “Thirty years ago Um al Kheir was one of the wealthiest Bedouin communities in the region. We had a herd of 1,600 sheep, whereas now we only have about 200 sheep left,” said Aziz. Food assistance has enabled Aziz to avoid resorting to such drastic coping strategies. “Thanks to the food rations, I don’t have to sell my sheep any more to feed my children.”

Of his future hopes, Aziz says: “I hope the demolition order on my house will be lifted and I want to repair the roof and walls of my house to make it more habitable, especially during the cold winters. To help us get by, I would like to setup small projects such as beekeeping, and maybe larger vegetable gardens.”

Assisting Khan al-Ahmar Bedouin

Khan al-Ahmar is one of the Bedouin communities located alongside the highway between Jerusalem and Jericho and at risk of forcible transfer. Food assistance from WFP and UNRWA helps residents to free up resources to buy vegetables. “We can’t produce enough vegetables for ourselves, so we buy them from a local vendor who comes to the village once a week,” says Maha, a 34-year-old woman living in the community. Maha uses the fortified wheat flour received through the food assistance program to make shrak, a thin flatbread baked on a large frying pan known as a saj. “We also use the chickpeas to prepare humous and the lentils to make soup,” she said.

[1] The number of residents and residential areas were estimated in a vulnerability profile project carried out in 2013. For further information see: http://data.ochaopt.org/vpp.aspx

[3] OCHA’s demolition database.

[4] See OCHA, Bedouin Communities at Risk of Forcible Transfer, September 2014.

[5] For further background see OCHA, Susiya: ACommunity at Imminent Risk of Forced Displacement, June2015.