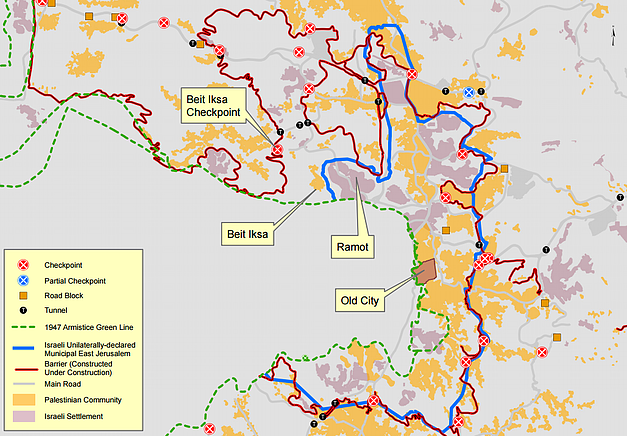

New access restrictions impact a Barrier-affected community in the Jerusalem area

Disruption of access to services and family life is expected to trigger further displacement

Beit Iksa village (pop. 2,000) is located in the north-west of Jerusalem governorate. Although not included within the municipal area of Jerusalem that was unilaterally annexed to Israel following the 1967 war, Beit Iksa initially retained its historic connections to the city. These links have been severed since the early 1990s when Israel began requiring Palestinians who hold West Bank ID cards to obtain permits to enter Israel and East Jerusalem.

The situation has been compounded since 2006 following completion of the Barrier, which left Beit Iksa on the Jerusalem side of the Barrier. The village has been physically separated from the wider West Bank by a permanent checkpoint installed in the Barrier limiting access to the village to residents and to Palestinians from nearby villages. At the same time, not only has the ban on access to municipal areas of Jerusalem remained in place, but in 2010 the road that connects Beit Iksa to East Jerusalem was blocked for vehicular movement, forcing Jerusalem ID holders to use a long detour via Qalandia checkpoint to commute between the village and East Jerusalem. The impact of these restrictions has been devastating in terms of social relations, service provision, construction and the implementation of projects.

Since the beginning of 2014, restrictions on entry to Beit Iksa by non-resident Palestinians with West Bank ID cards has intensified, including on traders, service providers and relatives. Starting in April 2014, soldiers staffing the checkpoint have requested that both individuals and organizations entering the village obtain a letter from Beit Iksa village council to justify their presence or activity there. In July 2014, a sit-in by Palestinians at the checkpoint to protest against the new restrictions prompted agreement on a coordination mechanism involving the Palestinian District Coordination Liaison (DCL). However, following the persistence of incidents of denied access, the Palestinian DCL has reportedly withdrawn its participation.

According to Kamal Hababeh, former head of Beit Iksa village council, people have slowly been moving out of the village since 2010 and this has greatly affected economic activity and construction. “For the first time this year, people were prevented from reaching Beit Iksa to visit relatives during Ramadan and Eid. If this continues, the future of the village will be very bleak indeed.” It is estimated that between 400 and 500 residents have left Beit Iksa since the construction of the Barrier and the closure of the road leading from the village to Jerusalem. This year, three households moved out of the village (see Moving from Beit Iksa).[1]

West Bank: Barrier and other access restrictions in the Jerusalem area, October 2014

Moving from Beit Iksa

Nizar Badran, a 50-year-old registered refugee, moved from the neighbouring village of Biddu to Beit Iksa in 2000 with his wife and five children. Beit Iksa is the address on Nizar’s ID card, while the address for the rest of his family is Biddu. According to Nizar, the family started facing problems at Beit Iksa checkpoint at the beginning of 2014 when Israeli soldiers regularly denied his wife and children access to the village on the grounds that Beit Iksa was not the address on their ID cards. Nizar obtained a letter from Beit Iksa village council that certified that his family lives in Beit Iksa. This provided a temporary solution until July when the soldiers at the checkpoint stopped recognizing the letter. There were several times when Nizar desperately tried to coordinate access for his family, including through the Palestinian DCL, without any success.

Nizar has tried to change the ID address of his wife and children to Beit Iksa, but has not yet succeeded in doing so. Following an incident in which his son was almost killed at the checkpoint in an altercation with soldiers when denied access, Nizar decided to move with his family to Biddu village, at least temporarily. They are currently living in an apartment in Biddu village owned by one of his cousins. Nizar said that he wants to continue living in Beit Iksa and visits his home there from time to time.

On 9 July 2004, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued an advisory opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory. The ICJ recognized that Israel ‘has to face numerous indiscriminate and deadly acts of violence against its civilian population’ and that it ‘has the right, and indeed the duty, to respond in order to protect the life of its citizens. [However], the measures taken are bound nonetheless to remain in conformity with applicable international law.

The ICJ stated that the sections of the Barrier route which ran inside the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, violated Israel’s obligations under international law. The ICJ called on Israel to cease construction of the Barrier ‘including in and around East Jerusalem’; dismantle the sections already completed; and ‘repeal or render ineffective forthwith all legislative and regulatory acts relating thereto’.

To mark the tenth anniversary of the ICJ advisory opinion in July 2014, OCHA is issuing a series of articles in the Humanitarian Bulletin to highlight the continuing humanitarian impact of the Barrier.

[1] Similar displacement is also taking place in nearby dislocated communities. According to An Nabi Samuel village council, 24 households comprising 125 people have moved out of the village in the past seven years as a result of restrictions on movement, access and the building of new homes. See ‘The case of dislocated communities on the Jerusalem side of the Barrier: concern over forced displacement’, OCHA Humanitarian Bulletin, March 2014.