Gaza fisheries: fishing catch Increases amid ongoing protection concerns

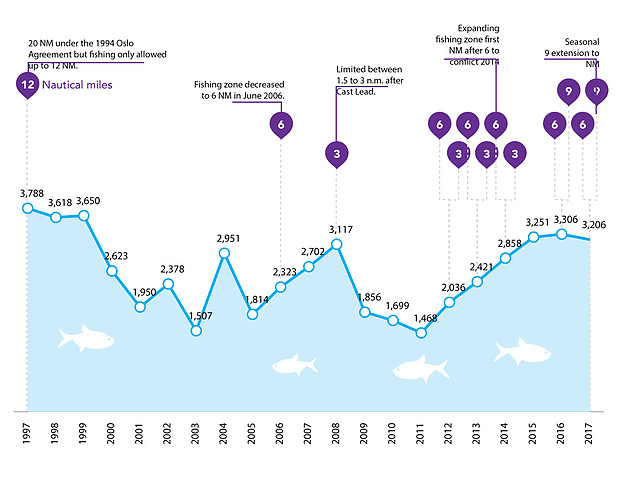

In 1994, a permitted fishing range of 20 nautical miles (NM) was agreed between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO).[1] In practice, Israel only allowed fishing up to 12 NM until 2006, when the fishing zone was reduced to six and later to three NM. According to the Israeli authorities, in recent years, Hamas has established naval forces with significant military capabilities, requiring the tightening of access restrictions at sea to prevent attacks, such as the infiltration of naval commandos.[2]

Fishing catch (in tons) and fishing limits (in NM)

Since the ceasefire agreement concluded in the wake of the August 2014 hostilities, the fishing limit has been fixed at six NM, with an extension to nine NM along the southern coast (between Khan Yunis and Rafah) twice a year during the sardine season, from April to June and from September to November. Such extensions in 2016 and 2017 have significantly increased the total catch, which reached their highest levels for the past 13 years. However, the catch remains mainly limited to low-value sardines, making it difficult for fishermen to earn a livable income. Additionally, practices used by the Israeli navy, and to a lesser extent by the Egyptian navy, to enforce the fishing limits, including the firing of live ammunition, have raised a range of protection concerns.

The fishing sector in the socio-economic context of Gaza

Within a context of high unemployment and food insecurity, the fishery sector remains a significant source of employment. Fish, particularly sardines, is also a major source of protein, micronutrients and essential Omega 3 fatty acids for Palestinians in Gaza and contributes to nutritional diversity. In 2017, 40 per cent of households in Gaza were estimated to be severely or moderately food insecure[3] and unemployment stood at 43.6 per cent,[4] particularly among vulnerable groups such as women and youth.

According to the Ministry of Agriculture’s Department of Fisheries, there are currently 3,700 registered fishers in Gaza who rely on the sector for their livelihood. It is estimated that Gazan fishers currently support 18,250 other people (based on an average household size of 5.7 people in Gaza).[5]

It is also estimated that a significant number of people rely on fishing-associated industries, including repairs and retailing. According to the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA), only 2,000 of those registered fish on a daily basis while the remaining 1,700 work sporadically, around once a month, because the income they generate does not cover their operating costs.

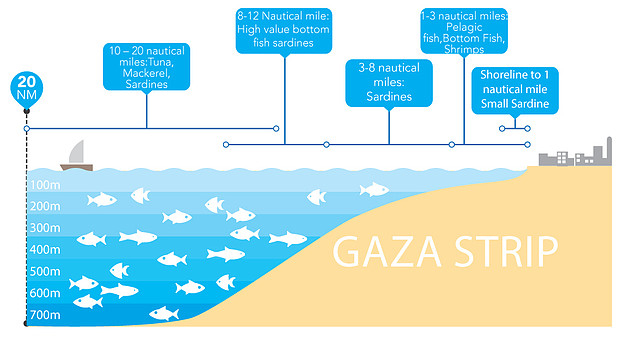

Fish catches and revenues have varied considerably over the years. While the fishing limit impacts both catch and revenue, revenues also vary according to the type and quantity of fish available in the given zone. The restriction of fishing to a small area near the coast leads to overfishing and has a negative impact on breeding grounds. According to the Department of Fisheries, the impact of the restrictions on the fishing zone to three NM in 2006 and 2007 only became evident in 2009 when fish breeding grounds in the permitted three NM zone were severely depleted.

Type of Fish Caught by Sea Depth and NM

Expansion of the fishing zone after 2012 led to a significant increase in both catch and revenue, particularly in 2016 following the seasonal expansion of the fishing zone to nine NM on the southern Gaza coast. In 2016, revenues increased proportionally more than the quantity of the catch due to the availability of other types of fish beyond the six NM limit that are more profitable than the fish available in shallow water. The same extension in 2017 resulted in a much lower increase in catch and revenue due to the unusually low fish supply that year. This could be addressed by the continued extension of fishing limits to nine NM or beyond, where fish supplies are less vulnerable to fluctuating conditions.

The Gazan fisheries sector lacks access to essential imports, including fibreglass, boat engines and spare parts, which are restricted by Israel as “dual use” items. Fishing nets and other items are often too expensive for fishermen on their limited income.

Gazan fishers were informally allowed to fish in Egyptian waters between 2011 and 2013, when access within Gazan waters was limited to six NM. During this period, fishermen were able to catch high-value fish more commonly found at 12 NM. According to the Department of Fisheries, a total of 180 tons of mullet was caught in Egyptian waters at 12 NM compared with 21 tons of mullet caught in Gazan waters at six NM during the same period.

According to the Department of Fisheries, a revival of the fishery sector would require the current fishing zones to be extended. A permanent extension of the fishing zone to nine NM throughout the year would likely result in an increase of approximately 20 per cent in both revenue and jobs. According to MoA, the extension of the fishing zone to 12 NM all year round could raise the fish catch to 5,000-6,000 tons, an increase of nearly 50 per cent. This could result in a 60-65 per cent increase in income if coupled with export facilitation, and could also ensure full employment of all current fishermen in Gaza.

An expansion would also release pressure on fish populations within the three to six NM zone, with a positive impact on the carrying capacity of fish stock. The fisheries sector would also benefit significantly from the easing of restrictions on imports of equipment to meet repair needs (both regular and increased demand resulting from damage during conflict and the confiscation of boats by the Israeli navy).

Continuing protection concerns and lack of accountability

Live ammunition continues to be widely employed by the Israeli navy to enforce the maritime limits. Overall, 213 shooting incidents were registered in 2017, resulting in one fisherman killed and 14 injured, including one child. Another fisherman died in unclear circumstances and 39 more were arrested, of whom three were children. During the first two months of 2018, 64 shooting incidents were recorded: one fisherman was killed and eight were injured. The fatality, Ismail Saleh Abu Riyalah, aged 18, died when the Israeli navy fired at his boat without a verbal warning or warning shots, reportedly at close range and in the absence of a threat to life or serious injury.

If arrested, fishermen report being interrogated about Palestinian armed groups and subjected to ill-treatment and verbal abuse prior to their release. This raises serious human rights concerns, including the right to life and respect for due process guarantees enshrined in international law.[6] In 2017, the Israeli navy confiscated 13 boats and another seven incidents of damage, confiscation and loss of fishing equipment were registered. In January and February 2018, four boats were confiscated and not returned, and one more was damaged.[7]

Under international law, the use of firearms should be strictly limited to situations of last resort, i.e. in response to an imminent threat to life. Otherwise, the use of firearms constitutes excessive and unlawful use of force.[8] Violations of these standards that result in casualties must be duly investigated by the authorities and accountability ensured promptly through independent, objective and impartial investigations. Civil remedies, including financial compensation, are also clearly established under international law.[9]

Fish culture to enhance production and sustain fisheries livelihood

Fish culture (both land and marine-based) has been introduced to Gaza to supplement traditional methods of fishing and generate sustainable livelihoods. Fish production generated from land-based fish culture has been increasing steadily from five tons in 2010 to 435 tons in 2017, according to the Department of Fisheries. The FAO of the UN is piloting a marine cage farm as a social business[10] owned and managed by fishery member institutions in the sea off Gaza to promote development of a marine aquaculture sector that will benefit the fishery community. The cage farm has the potential to promote greater productivity and incomes, and ensure the succession of a sustainable and resilient livelihood to younger fishing generations. Supported by the Government of Italy, this initiative delivers marine aquaculture technologies and capacity development to fishermen and the Gaza Fisheries Syndicate to enable operation of the marine cage farm as a social business. It also promotes access and links to markets. The pilot marine cage farm is expected to produce approximately 150 tons of sea bream per year, contributing an additional 4.5 to 5 per cent to the local fish market. The increased availability of fish is expected to make fish more affordable for consumers, improve consumption levels and dietary diversity, and contribute to the growth of exports and income.

Two cases of fishermen fatalities and lack of legal remedies

On 15 May 2017, Mohammad Mjid Fadil Bakr, aged 25, was killed while working on his fishing boat approximately three NM off the coast. Reportedly, the Israeli navy instructed the boat to stop by loudspeaker, while simultaneously opening fire. The boat disregarded the warnings and continued to move until a bullet hit the engine: Mohammad was shot in the back as he was trying to protect the engine. The victim was immediately taken by the navy to a hospital in Israel (Ashkelon), where he was pronounced dead.

On 4 January 2017, another fisherman, Mohammad Ahmad Jameel al Hisi, aged 33, went missing about five NM off the Beit Lahia coast in unclear circumstances. An Israeli navy vessel reportedly crashed into the victim’s boat which “was not visible due to the conditions out at sea”. He was later pronounced dead.

In the cases of the two fatalities, the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights (PCHR) requested the opening of criminal investigations by the Israeli Military Attorney General (MAG) and also filed civil complaints for compensation before the Israeli Ministry of Defense (MoD). There has been little response from the Israeli authorities in either instance. PCHR has received no response to criminal complaints filed regarding four other cases of injuries. Of 11 civil cases filed in 2017, only three responses acknowledging receipt have been received from the MoD.

* This article was contributed by the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO),

[1] Agreement on the Gaza Strip and Jericho, Cairo, 4 May 1994. A no-go zone one mile wide along Gaza’s boundaries with Egypt in the south, and another of one mile and half along Gaza’s boundaries with Israel in the north, were also established.

[2] 2017 Humanitarian Needs Overview, p. 7.

[3] 2018 Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO). Available here

[4] PCBS 2018, The Labour Force Survey Results 2017: Main Results. Available here

[5] PCBS 2015, Summary of Demographic Indicators in Palestine by Region. Available here

[6] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Articles 6, 7, 9, 10.

[7] Figures provided by al-Mezan Centre for Human Rights.

[8] Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials.

[9] ICCPR, Articles 2,14,26, and Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law.

[10] A social business is created and designed to combine commercial and social goals with an emphasis on the latter. Investment in social business should lead to equivalent increase in social impact. Profits realized by the business are reinvested in the business itself.