Food insecurity in the oPt: 1.3 million Palestinians in the Gaza strip are food insecure

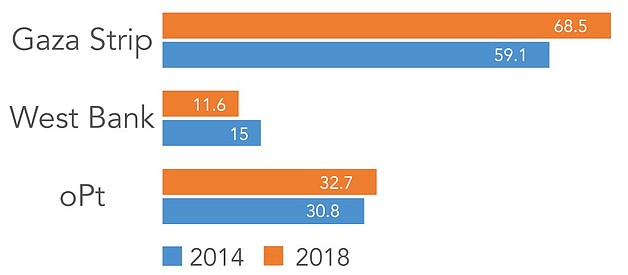

Over 68 per cent of households in the Gaza Strip, or about 1.3 million people, are severely or moderately food insecure, according to the preliminary findings of the latest Socio-Economic and Food Security Survey (SefSec) carried out in 2018. [1] This is despite the fact that 69 per cent of households in Gaza reported in the survey that they receive some form of food assistance or other forms of social transfers from Palestinian governmental bodies or international organizations. The current food insecurity rate in Gaza constitutes a rise of 9 percentage points from the equivalent figure for 2014 (59 per cent), the last time the SefSec was conducted. By contrast, food insecurity in the West Bank stands at nearly 12 per cent of households according to the same survey, down from 15 per cent in 2014.

Food insecurity in the oPt is primarily caused by limited economic access to food. The World Bank forecast economic growth of 1.7 per cent for the oPt in 2018, “declining significantly in per capita terms”. [2] In Gaza the economy is “in free fall, registering minus 6 per cent growth in the first quarter of 2018 ... (while) initial indications are that Gaza has further deteriorated in the second quarter.” While the situation in the West Bank is not as dire, “the economy is expected to slow considerably in the coming period”.[3]

The unemployment rate in the oPt has also increased in recent years and reached nearly 32 per cent in the third quarter of 2018; in Gaza the rate was almost 55 per cent, the highest ever recorded. Of the approximately 244,000 people recorded as “employed” in Gaza, about 62,000 are public employees on the PA’s payroll whose salaries have been cut since March 2017. Another 22,000 are employees recruited by the Hamas authorities who have only received part of their salaries on an irregular basis since 2014: in November some of these employees were paid their August salaries from the Qatari funding. Unemployment among youth in Gaza exceeded 70 per cent, and was even higher for females at 78 per cent in the second quarter of 2018. [4]

Food insecurity by area, in percentages of households

Poverty is one of the main determinants of food insecurity. The 2017 Household Expenditure and Consumption Survey found that the poverty rate in Gaza had increased from 38.8 to 53 per cent since the previous survey in 2011. Nearly two-thirds of the poor, or about 656,000 people, are considered to be living in “deep poverty”.[5]

The chronic energy deficit has placed additional pressure on farmers, herders and fishermen who are already experiencing an increase in agricultural input costs despite falling vegetable and poultry market prices, putting profitability and sustainability at risk. The electricity crisis made it difficult for households to refrigerate food items and caused increased expenditure and work for women as daily cooking or use of canned food is required.[6] The situation has improved with the recent boost to the electricity supply.

Food insecurity has been further jeopardized by the shortfall in funding to UNRWA and decreased support from the Palestinian Ministry of Social Development to the most vulnerable, leading to higher levels of household debt. Due to the timing of data collection, the full impact of these challenges might not be fully reflected in the 2018 SefSec findings, which indicated that the prevalence of food insecurity among refugees in the Gaza Strip is slightly lower (67.3 per cent) than among non-refugees (70.3 per cent).

Cash assistance response undermined due to lack of funding

Cash Transfer Programming (CTP) is increasingly recognised as a major modality of humanitarian assistance. This is particularly true in the Gaza Strip where years of blockade and conflict have decimated exports and private sector investments, making aid and remittances the almost exclusive source of foreign exchange inflow.

In the 2018 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) for the oPt, the humanitarian community appealed for $130 million for various cash assistance interventions in the Gaza Strip, including $95 million for food security and $34 million for temporary shelter cash assitance (TSCA) for those still displaced since the 2014 hostilities. By the end of November 2018, humanitarian organizations had received only $23 million, or 18 per cent of the requirements. This has prevented the delivery of the majority of the planned interventions. UNRWA was force to halt the distribution of TSCA entirely during the second half of 2018.

The two main modalities of cash assistance in the food security sector have been Cash for Work and Cash for Livelihood interventions. In 2018, UNRWA appealed for $63.6 million to offer short-term employ¬ment opportunities for more than 54,000 people, or the equivalent to over 5.5 million workdays. Such opportunities could have injected millions into the local economy, however, due to underfunding, less than 10 per cent of the appeal target was reached. Another 12 humanitarian partners requested $5.7 million for Cash for Livelihood, with only $1.1 million received by the end of November 2018.

Constraints on micro businesses indicative of broader livelihood crisis

Businesses in the Gaza Strip are mostly small, both in terms of the number of employees and the value of their assets. According to a 2017 survey by UNDP, the majority (88.8%) employ one to four workers. This small-scale private sector continues to operate under increasing internal and external stress resulting from the Israeli-imposed blockade and intra-Palestinian political divisions.

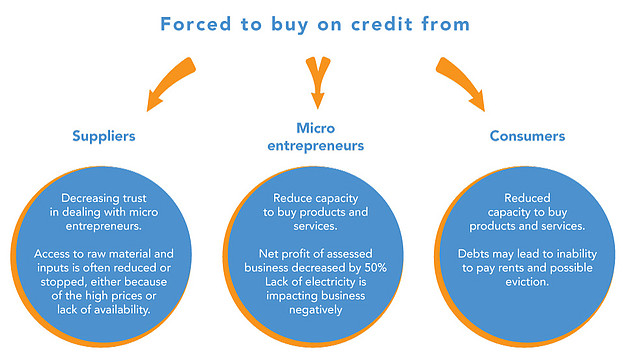

In September 2018 Action Against Hunger’s Food Security and Livelihoods team surveyed several beneficiaries of its Income Generating Activities to assess the impact of 2018 developments on the performance of the micro businesses. All the interviewees stated that lack of cash in the communities where the businesses are located forces their consumers and themselves to buy on credit.

The survey was conducted on behalf of the Cash Programming Working Group, which operates under the Food Security Sector, to coordinate, promote and facilitate sustainable activities related to Cash Programming in Palestine. The main mandate of the working group is to address all methodologies and standards of Cash Programming related to emergency interventions, medium and long-term food security related programs.

Cash assistance beneficiary progresses from struggling to feed her children to giving business tips

The hostilities had a destructive impact on this family. In 2014, an Israeli “warning” [7] missile hit the house, killing Wedad’s 13-year-old son, and destroying the house except for two rooms. The family was displaced twice in the past, as a result of the 2009 and 2012 hostilities.

‘We also lost our sheep, chickens and rabbits’, Asbita explains. ‘It was the business I took over after my husband’s death.’

Since 2014, Asbita and her son’s family of four children continue to live in the only two rooms that were not destroyed. Given their poor economic status, Wedad had moved back with her parents for a period of time as it is custom in Gaza, a woman is expected to go back to her own parents’ house if her husband is no longer able to cover the family expenses. In such cases, the children would then stay with the father, at his parents’ house. However, unlike many couples, Wedad returned to live with her family at her mother-in-law’s house.

‘It was too hard to be separated from my husband, he is my rock’, said Wedad. ‘We struggled to keep the children well fed and we reduced our own meals. We did not care about the quality of the food. We just did not want them to go hungry.’ She explained.

Even before the last war in 2014, as Wedad gradually took over responsibilities from Asbita who became ill, she went through many rough days to support the family. ‘I had to save up to buy milk for my children. Food in general had become more expensive and therefore scarcer since the beginning of the blockade.’

Despite the heavy losses during the last hostilities, the family resumed the sheep rearing business after the war with Action Against Hunger’s cash assistance and training. Asbita now takes care of the financial side of things, while the animals are Wedad’s responsibility.

‘We were taught to make sound business decisions like buying fodder in bulk to ensure availability and avoid sudden price increases. With the first payment, we prepared the barn, and with the second one we bought the sheep.’ Said Asbita.

Wedad describes with pride how they are now able to provide their children with vegetables, fruits and even meat up to twice a week. The family has future plans for the business. They want to expand into poultry and rabbits again. ‘A friend recently asked me for tips on how to create her own business’, Wedad smiles. ‘I offered her my business plan!’

[1] Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics and Food Security Sector, Socio-Economic and Food Security Survey 208 Preliminary results.

[2] World Bank, Economic Monitoring Report to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee, 27 September 2018, para. 1. “Moreover, there are significant downside risks to this forecast, especially with concerns surrounding the Israeli legislation to reduce clearance revenues, and the potential for increased tensions to spill over into unrest in Gaza.”

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid. para. 15.

[5] Poor people are defined as those living on less than $4.6 per day, including social assistance and transfers, the minimum to cover basic household needs. Every second person in Gaza, over one million people, is now considered poor, including over 400,000 children. According to the survey, without social assistance and transfers, the poverty rate in Gaza would have reached nearly 60 per cent, and deep poverty more than 42 per cent.

[6] GBV Sub-Cluster (2017). The Humanitarian Impact of Gaza’s Electricity and Fuel Crisis on Gender-based Violence and Services, May 2017.

[7] “Warning missiles”, also referred to as “roof knocking” refer to small missiles fired by the Israeli forces with the stated objective of warning inhabitants to evacuate ahead of the firing of larger missiles or missiles with higher impact. More information can be viewed in 6 March 2013, Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the implementation of Human Rights Council resolution S-9/1 and S-12/1, A/HRC/22/35/Add.1.