Settlement expansion around an Israeli-declared “nature reserve”

Access restrictions and settler harassment undermine livelihoods and generate risk of displacement

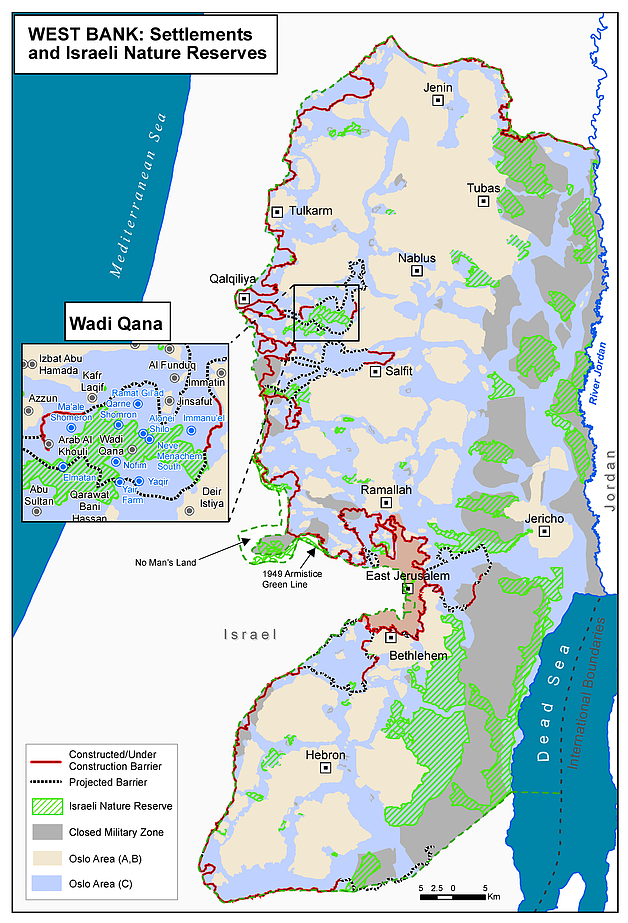

Recent settlement activities and measures in the Wadi Qana area of Qalqiliya governorate have raised concerns because of their potential impact on already vulnerable Palestinian communities. This area was designated as a nature reserve by the Israeli authorities in the 1980s, resulting in severe restrictions on Palestinian landowners wishing to use the land for farming and grazing. The area of the reserve is surrounded on all sides by ten Israeli settlements, including two unauthorized outposts (El Matan and Alonei Shilo).

In June of this year, the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA) deposited for public review a detailed outline plan aimed at retroactively “legalizing” the El Matan outpost and its access road.[1] Since part of the plan’s area (including some already existing structures) lies within the boundaries of the nature reserve where development is prohibited, the ICA also issued an order amending the nature reserve’s boundaries to exclude the proposed area (approximately 100 dunums).[2]

The land allocated to El Matan was declared “state land” in the past by the ICA and incorporated into the municipal boundaries of the Ma’ale Shomron settlement, but Palestinians from nearby communities claim ownership of this land and have submitted objections to the plan.

Two small Palestinian herding communities (Wadi Qana and Arab Al Khouli) are located within and adjacent to the nature reserve and have a population of about 85 people. These communities, which have reportedly lived in this area since the 1940s, have been particularly affected by the restrictions imposed by the Israeli authorities and the settlement activities in the area, resulting in displacement and the risk of displacement.

According to the representatives of one of these communities (Arab Al Khouli), in recent months they have faced repeated incidents of harassment by armed settlers. These incidents typically involve security coordinators from El Matan and Ma’ale Shomron blocking access to the area when residents bring fodder or water for their livestock. The residents also reported that access to water for their domestic and livelihood needs has been severely undermined in recent years following water extraction from the underlying aquifer by Ma’ale Shomron settlement, which reduces (and for part of the year eradicates) the discharge of the spring, which has served as the traditional water source for the community. Community representatives reported that over the past three to four years, five families left the area because they could not sustain their herding livelihoods in this area (approximately 600 sheep), and relocated to the nearby towns of Azzun and Kafr Thulth.

Palestinian farmers from other communities also reported increased restrictions by the Israeli authorities on the cultivation of their land in this area. In April 2012, the ICA issued evacuation orders for several plots of land planted with approximately 1,400 olive trees (2 to 6 years old) owned by farmers from Deir Istiya village. According to the ICA, this cultivation had expanded inside the nature reserve area without authorization. Following a compromise reached in legal proceedings in January 2014, the ICA uprooted and seized 1,000 of these trees.

What are Israeli “nature reserves” in the West Bank?

Since the beginning of the occupation, the Israeli authorities have designated 76 areas, covering approximately 13 per cent of the West Bank (approximately 578,000 dunums), as “nature reserves”, with the stated objective of protecting the environment and wildlife in those areas. The majority of such reserves are located along the Jordan Valley and Dead Sea area.[3]

Israeli military orders prohibit actions resulting in “harm” to the nature reserve, including acts that “change the form or natural position, or artificial disturbance of the natural developmental course [of the nature reserve].”[4]This provision has been interpreted by the Israeli authorities as a comprehensive ban on the use of the designated areas for residential, agricultural or grazing purposes, except for such uses that have been recognized as ongoing prior to the declaration of the area as a nature reserve.[5]

The actual enforcement and interpretation of this provision has varied greatly over time and in different areas. In recent years, enforcement in some of the Jordan Valley reserves has been more apparent through the imposition of fines on herders grazing their livestock in the area.

Only four of the declared nature reserves have been developed by the Israeli authorities to accommodate visitors (all in the Dead Sea area).[6] Analysis of a 2014 aerial picture of the West Bank also indicates that dozens of Israeli settlements and settlement outposts have a portion of their outer limits encroaching into areas designated as nature reserves.

Nearly one quarter of the total area designated as nature reserves was subsequently declared as a “firing zone” for military training, a fact calling into question the stated objective of protecting wildlife.

[2] Chaim Levinson and Zafrir Rinat, Haaretz, Oct. 2, 2014

[3] These areas include large swathes of land in Bethlehem governorate that were declared as nature reserves as part of the Wye River Memorandum of 1998, with the intention that they would be handed over to the Palestinian Authority.

[4] Order Regarding Preservation of Nature (No. 363, 1969)

[5] B’Tselem, Dispossession and Exploitation: Israel’s Policy in the Jordan Valley and Northern Dead Sea, 2011.

[6] Wadi Qelt (Ein Prat), Ein Fashkha (Einot Tzukim), Qumran, and the Hashmonaim palaces.