Olive harvest season: expected record yield compromised due to access restrictions and settler violence

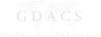

The annual olive harvest, which takes place every year between October and November, is a key economic, social and cultural event for Palestinians. In the West Bank, more than 10 million olive trees are cultivated on approximately 86,000 hectares of land, representing 47 per cent of the total cultivated agricultural area. Between 80,000 and 100,000 families are said to rely on olives and olive oil for primary or secondary sources of income, and the sector employs large numbers of unskilled laborers and more than 15 per cent of working women.[1] According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the olive oil yield for the West Bank in 2019 is estimated to reach a record 27,000 tons, which is an 84 per cent increase over the previous year. The estimated record yield this year is due to the alternate fruit-bearing “on and off seasons” and less infestation by the olive fruit fly during the current season.[2]

Between 80,000 and 100,000 families are said to rely on olives and olive oil for primary or secondary sources of income, and the sector employs large numbers of unskilled laborers and more than 15 per cent of working women.

In some areas, the realization of a potential record yield is compromised due to access restrictions and attacks and intimidation by Israeli settlers. Palestinians with olive groves located in the closed area between the Barrier and the ‘Green Line’ (also known as the ‘Seam Zone’), and in the vicinity of Israeli settlements, face year-round access restrictions and threats that prevent them from safely maintaining their olive-based livelihoods.

To support affected farmers and mitigate the impact of these challenges, humanitarian partners are carrying out a series of activities coordinated by the Protection Cluster, including a protective presence; in-kind assistance; psychosocial support; and legal counselling.

Olive oil yield in the West Bank in tons

Barrier permits and agricultural gates

Israel began building the Barrier in 2002, following a wave of Palestinian attacks, including suicide bombings inside Israel, with the stated aim of preventing such attacks. The majority of the Barrier’s route, however, is located within the West Bank.

The land located in the ‘Seam Zone’ has been declared closed under an Israeli military order.[3] Palestinian farmers and agricultural workers require special permits or ‘prior coordination’ to access farming land in this area.[4]

In its Advisory Opinion of 2004, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) established that the sections of the Barrier that run inside the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, together with the associated gate and permit regime, violate Israel’s obligations under international law. The ICJ called on Israel to cease construction of the Barrier inside the West Bank, to dismantle the sections already completed and repeal all legislative measures related to it. The decision has not been acted upon.

While the stated objective of the Barrier is to prevent violent attacks in Israel, permit applicants are increasingly rejected for a variety of bureaucratic reasons, rather than on security grounds.

According to official data obtained by the Israeli NGO HaMoked, the approval rate for permits for landowners fell from 76 per cent of applications in 2014 to 28 per cent in 2018 (as of 25 November). Permits issued for agricultural workers to enter these areas declined from 70 per cent of applications to 50 per cent in the same period.[5]

While the stated objective of the Barrier is to prevent violent attacks in Israel, permit applicants are increasingly rejected for a variety of bureaucratic reasons that include ‘no connection to the land’ or ‘not having enough land’, rather than on security grounds. Some 83 per cent of the requests in the data obtained by HaMoked were denied for failing to meet one of these bureaucratic criteria. In September 2019, the Israeli military issued a new set of procedures regulating Palestinian access to the Seam Zone which may further undermine the agricultural livelihoods of affected farmers (see box).

Trees vandalized by Israeli settlers

If granted approval, farmers must cross designated Barrier gates or checkpoints to reach the closed area. During the 2018 olive harvest, there were 77 operable gates, of which 55 opened only during the few weeks of the olive harvest, and only for limited hours on those days, and remained closed the rest of the year.[6]

Attacks by settlers

Olive-based livelihoods in many areas of the West Bank are also undermined by Israeli settlers who uproot and vandalize olive trees, and intimidate and physically assault Palestinian farmers, including during the olive harvest season.

Settler attacks have been on the rise in recent years: between January and October 2019 OCHA and partners have recorded a monthly average of 27 attacks resulting in Palestinian casualties or damage to property, compared with 25 in 2018, 14 in 2017 and 8 in 2016. The incidents recorded so far in 2019 resulted in damage to over 6,200 (mostly olive) trees, nearly half of them in the Nablus governorate (mostly around Yitzhar settlement), followed by Ramallah and Hebron governorates.

The incidents recorded so far in 2019 resulted in damage to over 6,200 (mostly olive) trees, nearly half of them in the Nablus governorate.

In October 2019, in the context of the olive harvest, humanitarian partners recorded a total of 26 incidents where Israeli settlers targeted farmers, trees or olive produce. This represents an increase compared with 19 and 20 incidents for the same period in 2018 and 2017 respectively.

As the occupying power, Israel has the obligation to protect Palestinian civilians from all acts or threats of violence, including by Israeli settlers, and to ensure that attacks are investigated effectively and perpetrators held accountable. The failure to do so has been a longstanding concern of the humanitarian community in the OPT and is believed to contribute to the persistently high levels of settler violence.[7]

Access restrictions to areas around settlements

Dozens of Palestinian communities in the West Bank have land within or in the vicinity of Israeli settlements. Much of this land has been declared by the Israeli authorities as a closed military area and can be accessed by Palestinian farmers only following authorization by the Israeli authorities, also known as ‘prior coordination’. Such authorization is generally granted for a limited number of days during the harvest and ploughing seasons.

The Israeli authorities have justified this practice citing the risk that harvesting activities, which involve the increased presence of farmers and their families in the field, could be exploited by terrorist groups to carry out attacks against adjacent Israeli settlements.[8]

The fact that Israeli soldiers are usually deployed around the affected olive groves during the ‘coordination periods’ is believed to have contributed to the reduction of settler attacks during the harvest season itself. However, as is the case regarding the Seam Zone, the restrictions imposed on access by farmers to their olive groves in the vicinity of settlements during most of the year impede their ability to carry out essential maintenance works, thereby undermining the productivity of the trees.

Often, the farmers would discover the damage sustained only months later when the next round of coordinated access is granted.

Moreover, although access by settlers to these areas is also prohibited, in some cases the location of the affected groves in the immediate vicinity of the settlements’ built-up areas, including within their fenced area, and the prolonged absence of the Palestinian landowners, has facilitated vandalizing of trees by settlers. Often, the farmers would discover the damage sustained only months later when the next round of coordinated access is granted.

Humanitarian response

To mitigate the impact of some of the aforementioned challenges, humanitarian partners carried out a mapping exercise that identified ‘hotspots’ of potential settler violence and access restrictions. The mapping allows humanitarian partners to provide a coordinated protective presence; in-kind assistance; psychosocial support; legal assistance; and to coordinate detailed timetable plans with Palestinian farmers and with military forces to accompany the harvest season. Humanitarian partners are providing a protective presence in at-risk areas with a dual objective: to deter potential attacks and to document incidents.

OCHA and humanitarian partners have participated in various olive harvest briefings provided by the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA), in which the ICA informed the international community that it aims to reduce friction, particularly on land surrounded by settlements, and accompany the farmers to ensure that harvesting is done without harassment.

The protective presence is, however, undermined by funding gaps. The Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine and Israel (EAPPI), one of the main organizations carrying out this activity, has had to reduce its protective presence during the olive harvest in 15 of the 32 communities they serve.

Limited and unpredictable access

Hiyam Ahmad Jumaa, a 58-year-old widow with ten children, lives with her adult son in Beit Surik village in western Ramallah governorate. She owns 22 dunums of land planted with olive, figs, grapes, peach and pomegranate trees. Since the Barrier was built in 2004, she is disconnected from her land and requires ‘prior coordination’, i.e. special authorization by the Israeli authorities, to access it.

“Our main access problem is not necessarily during the olive harvest. To maintain our trees we need to reach our land during the whole year, but we are only allowed to access twice a year for a few days.”

“Our main access problem is not necessarily during the olive harvest,” said Hiyam. “To maintain our trees, especially the pomegranate, grapes and peach trees, we need to reach our land during the whole year, but we are only allowed to access twice a year for a few days. Most of these fruit trees are currently not producing anything.”

When OCHA arrived on 31 October at around 9 am to “Barrier Gate 105”, which leads to Hiyam’s land, she was waiting with her two sons for the Israeli soldiers to open the gate. “The gate is supposed to be opened at around 6:30. We have been standing here since then but nobody showed up. Yesterday they opened it at 9:30 and the day before at 12:30 pm,” lamented Hiyam.

New standing regulations on the Seam zone

New standing regulations pertaining to the permit regime for Palestinians to cross the Barrier were issued by the Israeli military ahead of the current olive harvest season. They have two major implications, particularly for Palestinian farmers:

Downgrading the purpose of access. Whereas previous regulations stated that the purpose of farmer permits is to “preserve connection to the land”, the new regulations state that the purpose is “to enable agricultural cultivation according to agricultural need, based on the size of the plot and the type of crops, while preserving connection to the land.” (Section C, paragraph 2). Palestinian landowners and their families, therefore, will not be able to visit their own land for recreation or any other purpose except cultivation.

Limiting entry even for those granted permits. For the first time, the new regulations specify “Number of Yearly Entries” (Section C, paragraph 5). Under the previous regulations, the access of permit holders to their land was only subject to the opening modality of the relevant agricultural gate. Entry for farmers with olive groves, for example, is set at 40 days a year.

[1] PALTRADE, The State of Palestine National Export Strategy- Olive oil sector export strategy 2014 – 2018. According to PALTRADE, the entire olive sub-sector, including olive oil, table olives, pickles and soap, is worth between $160 and $191 million in good years.

[2] Ministry of Agriculture (MoA).

[3] In the northern West Bank, the land between the Barrier and the Green Line was declared closed by military order in October 2003. In January 2009, the closed area designation was extended to all or part of areas between the Barrier and the Green Line in the Salfit, Ramallah, Bethlehem and Hebron districts, plus to various areas between the Barrier and the Israeli-defined municipal boundary of Jerusalem.

[4] Of the 77 agricultural gates that operated during the 2018 olive harvest season, 47 required access permits and 30 operated via prior coordination.

[5] The data were obtained following a freedom of information request by HaMoked and, following no substantive response, a petition to the Israeli High Court of Justice.

[6] An additional nine gates are considered ‘weekly’ in that they open for some day(s) of the week throughout the year in addition to the olive season. Only 13 gates along the completed 465 kilometers of the Barrier open daily.

[7] According to the Israeli human rights organization Yesh Din, of 185 investigations monitored by the organization which were opened between 2014 and 2017 and reached a final stage, only 21, or 11.4 per cent, led to the prosecution of offenders, while the other 164 files were closed without indictment.

[8] This justification was given in a recent submission by the Israeli authorities to the Israeli High Court of Justice in response to a petition filed by Palestinian farmers from Qariut village (Nablus) together with the Israeli human rights organization Yesh Din: HCJ 6949/19, Head of Qariut Village Council and others vs IDF Commander in the West Bank, State Response, para. 6, 7 November 2019.