Locked in: movement of people to and from Gaza back to pre-2014 conflict levels

The volume of people allowed to move in and out of Gaza has declined further since the beginning of 2017 in comparison with the previous two years, particularly via the Israeli-controlled crossing (Erez). Movement via Rafah, the Egyptian controlled crossing, also remains at extremely low levels. This has exacerbated the isolation of Gaza from the remainder of the OPT and the outside world, further limiting access to medical treatment unavailable in Gaza, to higher education, to family and social life, and to employment and economic opportunities. The tightening of restrictions in recent months has also obstructed the movement of national staff employed by the UN and international NGOs and impeded humanitarian operations.

The Erez Crossing

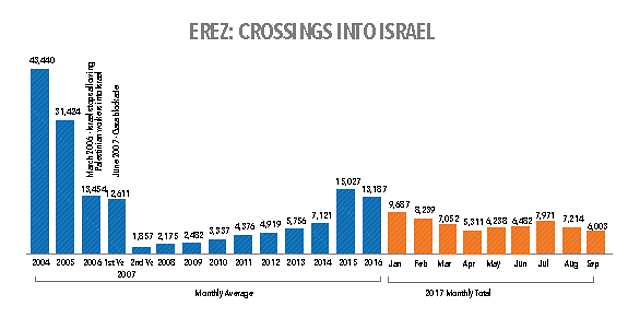

In September 2017, some 6,000 departures were registered via the Erez Crossing. This is 17 per cent below the monthly average since the beginning of the year, and 55-60 per cent below that of 2016 and 2015 averages.[7] Following the 2014 hostilities, the movement of people via the Erez crossing gradually increased, reaching a peak in mid-2016, after which this trend reversed.

In September 2017, some 6,000 departures were registered via the Erez Crossing. This is 17 per cent below the monthly average since the beginning of the year, and 55-60 per cent below that of 2016 and 2015 averages.[7] Following the 2014 hostilities, the movement of people via the Erez crossing gradually increased, reaching a peak in mid-2016, after which this trend reversed.

The Erez crossing is vitally important as it controls the movement of people between Gaza and the West Bank, and also entry to the Israeli labour market. Under a policy implemented since the beginning of the second Intifada in September 2000, citing security considerations, and tightened after June 2007 following the takeover of Gaza by Hamas, only people belonging to certain Israeli-defined categories are eligible for an exit permit, subject to a security check.

In recent years, these categories have included patients referred for medical treatment outside Gaza and their companions; traders; staff of international organizations; and exceptional humanitarian cases. Most people in Gaza are ineligible for exit permits, regardless of their individual security profile.

Although comprehensive data on permit applications and responses are unavailable, given that the ‘eligible categories’ have remained unchanged, the decline in movement since mid-2016 can be attributed to a tightening of the security criteria applied to eligible applicants.

The Rafah Crossing

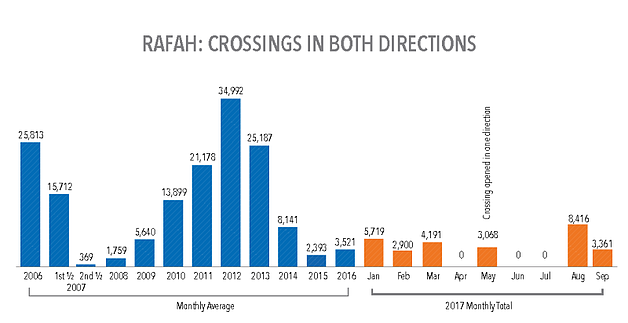

During September, the Rafah crossing between Gaza and Egypt was opened for five days to allow 3,361 pilgrims to return to Gaza. During August the crossing was opened for a total of seven days, for exits only, including one day for the exit of a Hamas delegation, and the other six for pilgrims heading to Mecca and a minimum number of others.[8]

The monthly average of crossings so far in 2017 is slightly below that for 2016, and a fraction of the equivalent figure for the 2012 peak. Between mid-2010 and mid-2014, the Rafah crossing operated fairly regularly and became an alternative to the highly restrictive Erez crossing. Following an attack against Egyptian forces in September 2014, the crossing was officially shut down and has opened only erratically since. As with Erez, only certain categories, including patients, students and foreign visa holders, can register on a waiting list administered by the Hamas authorities pending the crossing being reopened; at present, over 20,000 people are registered.

Referral of patients remains highly constrained

* This section was contributed by World Health Organization (WHO)

Patients referred for medical treatment at a hospital in the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), Israel or Jordan, are among the few eligible to apply for exit permits through the Erez crossing. In August, 1,883 permit applications were submitted, the lowest such figure since December 2016 due to the slow processing of requests for financial approval by the Palestinian Ministry of Health in Ramallah.[9] The top three specialties that accounted for approximately half of applications were oncology, haematology and paediatrics.

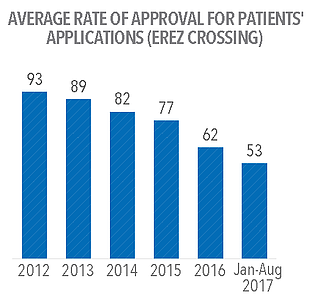

Of the applications submitted, some 55 per cent were approved, three per cent rejected, and the rest were unanswered by the time of the hospital appointment, requiring the patient to make a new appointment and resubmit the permit application. The average approval rate so far in 2017 for this type of permit stands at 53 per cent, down from 93 per cent in 2012, and marking the fifth consecutive year of decline.

This decline is occurring alongside a gradual increase in the absolute number of referrals and related permit applications to West Bank hospitals in the wake of stricter access constraints at the Rafah crossing. The increase in non-approved applications over recent years can be accounted for by an increase in the number of patient applications delayed, rather than denied. This suggests an increasingly constrained shortage of capacity in the resources allocated for the Israeli authorities to process this type of application.

This decline is occurring alongside a gradual increase in the absolute number of referrals and related permit applications to West Bank hospitals in the wake of stricter access constraints at the Rafah crossing. The increase in non-approved applications over recent years can be accounted for by an increase in the number of patient applications delayed, rather than denied. This suggests an increasingly constrained shortage of capacity in the resources allocated for the Israeli authorities to process this type of application.

According to new Israeli guidelines effective from May 2017, patients are required to submit non-urgent applications at least 20 working days prior to the date of their hospital appointment, doubling the period required previously.

During the few days the Rafah crossing opened in August, 22 patients and 20 companions were allowed to enter Egypt. This means that a total of 1,200 patients left Gaza via Rafah since the beginning of 2017; prior to July 2013, more than 4,000 Gaza residents crossed Rafah to Egypt each month for health-related reasons. No medical aid or medical delegates entered Gaza via Rafah during August.

Restrictions on humanitarian staff

The movement of humanitarian personnel to and from Gaza has also been subject to increased constraints that hampers the ability of staff to properly supervise and coordinate operations and training.

As for all other Palestinians, national staff employed by the UN or international NGOs must obtain a permit to exit Gaza via Erez. In August, half of the applications were approved and the rest had received no response by the scheduled travel date, with only one application rejected. This is in line with the permit delays recorded since the beginning of the year and represents an increase over figures for 2016.

In September 2017, the Israeli authorities informed agencies that the processing time for long-term permits will be 55 working days and 70 for travel abroad. This is a change from the 14 days required at the beginning of 2017, subsequently extended to 26 days before this last announcement. According to the Israeli authorities, this is part of a stricter vetting process by Israel’s security services. The maximum validity for long term permits has been extended from six to nine months.

In July 2017, the Israeli authorities announced a series of additional restrictions on items that can be carried by people leaving via Erez, primarily electronic devices other than cellular phones, toiletries and food items, effective from August. This restriction prevents staff from carrying their laptops with them, and undermines work and dignity. The UN has objected to these measures and continues to seek their immediate termination.

Mahmoud: got a scholarship but cannot attend his university

Mahmoud, 24 years of age, graduated from the School of Law at Al-Azhar University in 2015. He applied for a scholarship to study ‘Conflict Management and Humanitarian Work’ at the Al-Doha Institute for Higher Education in Qatar and was only one of only 20 students, and the only Palestinian, accepted from 3,500 students who applied from all over the world. The scholarship is for two years and covers all travel, accommodation, and tuition costs. It offers outstanding students the opportunity to work as instructors while studying and after graduation.

In August, at his third attempt, Mahmoud managed to register with the Ministry of Interior Traveler Registration Office in Gaza to exit Gaza, via Egypt, through the Rafah crossing. He also enlisted the support of the Qatari Committee for Reconstructing Gaza to coordinate with the Hamas authorities to coordinate his exit through that crossing.

Given that the Rafah crossing is unpredictable and usually closed, as an alternative, Mahmoud requested a ‘non-objection letter’ from the Jordanian Representative Office in Ramallah to travel via the King Hussein bridge; this was approved after two weeks. To go to Jordan Mahmoud needs an Israeli-issued permit to exit Gaza via the Erez crossing, although he knew that only a very small percentage of students succeed in obtaining such a permit. He applied anyway and kept checking with the Ministry but has received no response.

Obligatory introduction classes in Doha commenced on 17 September and Mahmoud had to obtain an exemption because of his inability to travel. Lectures began on 24 September with a grace period until 1 October. Although the Institute is sympathetic, Mahmoud will lose his scholarship if he is not present in Qatar by that date.

In a final attempt to obtain a permit to cross via Erez, Mahmoud is seeking the assistance of Gisha, an Israeli human rights organization. According to Gisha, a total of 362 students from Gaza who have won places at colleges and universities abroad have applied to leave Gaza via Erez since January 2017. Some 73 have been granted permission, seven have been refused, 50 were returned or placed under review, and 239 applications remain pending. The Palestinian Civil Affairs Committee in Gaza advises students to allow 50 business days for applications filed with them to be passed on to the Israeli authorities and a decision made, but even that amount of processing time is often inadequate because of processing delays

[7] The number of ‘exits’ is significantly higher than the actual number of people as some permit holders make more than one crossing during the time their permit is valid.

[8] During September, goods also entered via Rafah, including over 16 million litres of diesel fuel for the Gaza Power Plant.

[9] Apparently as part of the ongoing dispute between the Ramallah government and the de facto authorities in Gaza.