The impact on women of the Great March of Return

The impact of violence and casualties incurred during Gaza’s Great March of Return (GMR) demonstrations differs by sex due to social norms.

Between May and June 2018, UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund) carried out a rapid assessment to identify the specific impact of the GMR on Palestinian women and girls. It consisted of five focus discussions and ten in-depth structured interviews. Each focus group was composed of women who participated in or were directly affected by the demonstrations, along with female representatives of institutions providing social services to women.

Virtually all participants expressed a high level of support for the GMR and its underlying motives, namely to reaffirm the right of return for Palestine refugees, and to protest the longstanding Israeli blockade on Gaza with its adverse impact on the life and livelihoods of Gazans.

Most women indicated that consent for them to participate in the demonstrations had to be given by the male figure considered the head of the family: their husband or father. Despite the conservative social and cultural norms prevailing in Gaza, when such consent is given, women’s participation does not generate fear of negative repercussions. According to the focus group participants, women attend demonstrations more frequently on days other than Friday, when women traditionally have home duties as it is the weekend and a day for family activities. There is also a perception that demonstrations on Fridays are more violent than during the rest of the week.

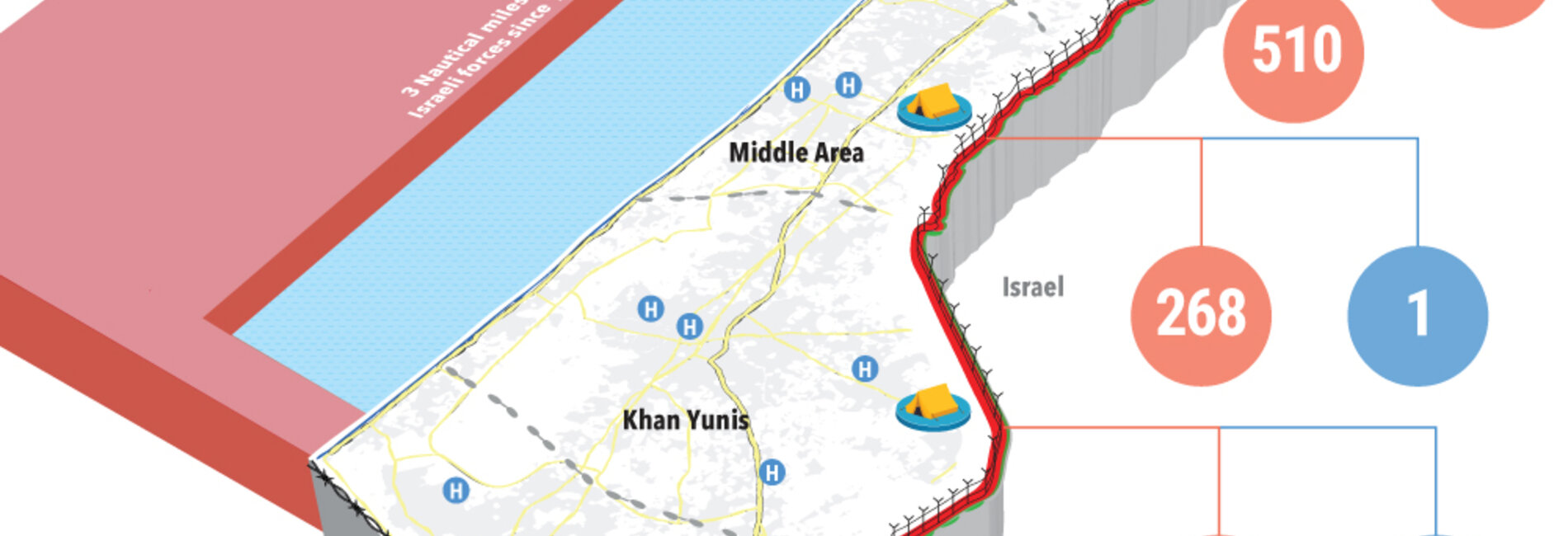

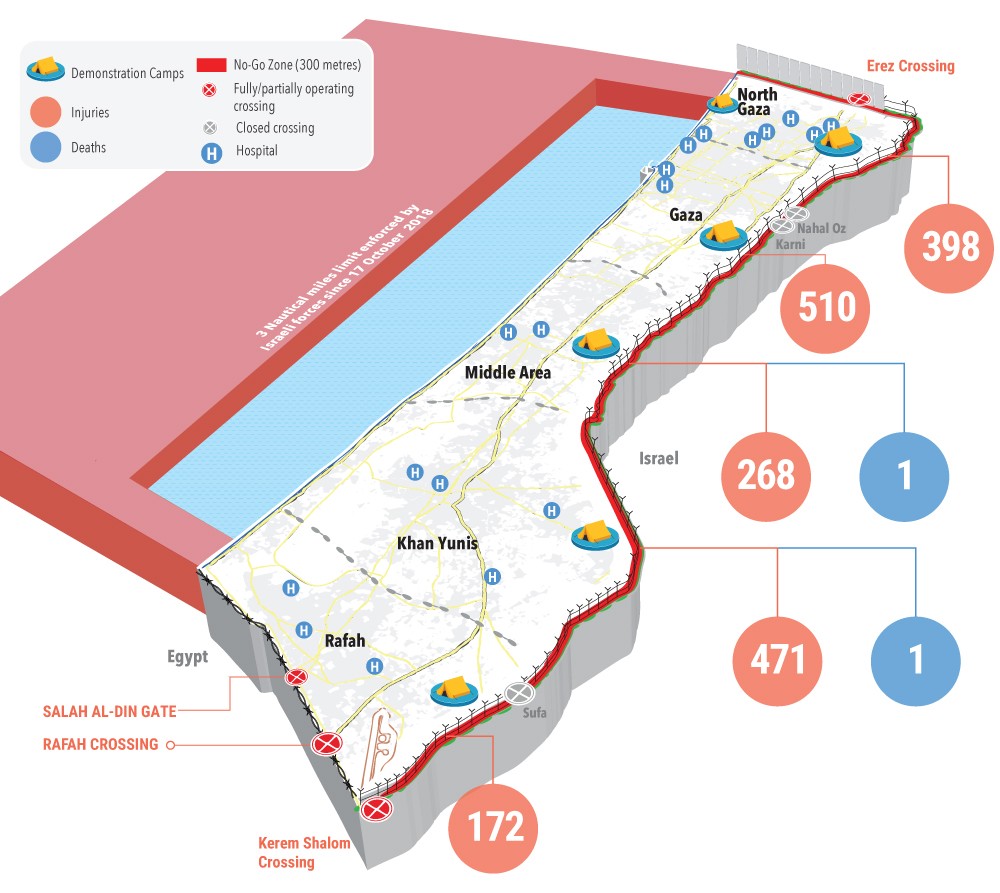

Women killed and injured

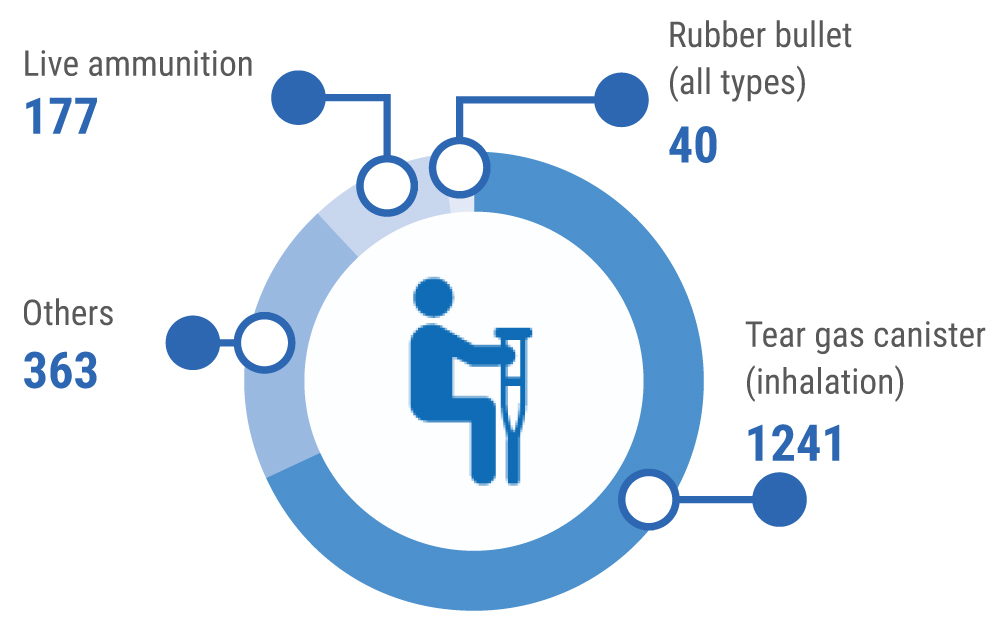

From the start of the GMR demonstrations on 30 March 2018 up to 30 November 2018, one woman and one girl were killed by Israeli forces, and over 1,800 other women and girls were injured. Women and girls account for about one per cent of all deaths and eight per cent of all injuries in this context. Of the female injuries, including those treated in the field, 68 per cent were due to tear gas inhalation and ten per cent to live fire.

Women and girls injured in Friday demonstrations between

30 Mar-30 Nov by type of weapon

Despite the relatively low proportion of injuries among females, the consequences of an injury are often harsher for women and for the rest of the family, particularly when the injured female is a mother. Some participants indicated that women are expected to continue fulfilling their home duties despite an injury. Others highlighted that injured women rely on other family members to access medical treatment because of the norm that women should not leave their homes unaccompanied. Some women also pointed out that a girl or young woman with a serious injury may find their chances of marrying impaired.

Several participants reported that they refrained from receiving medical treatment following severe tear gas inhalation during a demonstration to avoid possible tension with their husbands. One of the participants said: “My husband knows I am attending but is not happy about it. He told me I am free to go but I am responsible for whatever happens to me. I was affected by tear gas inhalation many times. Once I received first aid at the field hospital but asked not to register my details. If my husband knew about it he would prevent me from going next time.”

Female casualties in GMR demonstrations

30 Mar - 30 Nov 2018

The impact of casualties among other family members

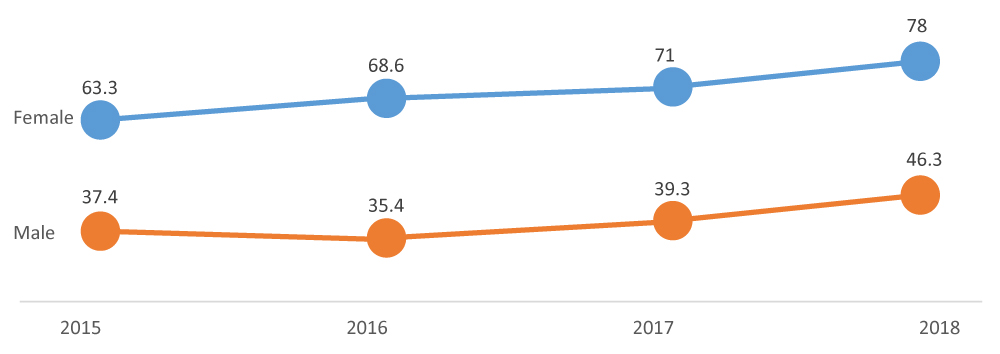

All participants and interviewees agreed that the death of a primary breadwinner has a direct and immediate impact on the living conditions of the widow and children. Given the socio-economic situation in Gaza, the opportunities for women to fill the income gap are minimal. In the third quarter of 2018, less than 26 per cent of women in Gaza were participating in the labour force (i.e. working or looking for a job) and 78 per cent of those were unemployed (versus 46 per cent of men).

Under current social norms, the parents or brothers of a male who is killed are expected to provide for the needs of the orphan children, particularly if the wife/mother does not have an income. Customarily, the husband’s family (rather than that of the wife) is the one entitled to the social benefits paid by the authorities or civil society institutions following the death, often exacerbating the widow’s loss of control over her life and children. Focus group participants indicated that most women suffer from lack of knowledge about their rights and are unaware of organizations that provide counselling and support.

Unemployment rates on third quarter of the year in Gaza, by gender

In the customary division of labor at home, the treatment of an injured family member is mainly the responsibility of the mother or wife. The huge number of people injured since the beginning of the GMR demonstrations, compounded by shortages of electricity, drugs and equipment, has forced hospitals to release patients prematurely and hand over treatment to the families. “This is extremely tiring and stressful, and it comes on top of our normal work at home”, said one of the participants. Another woman added that due to the family’s poor economic circumstances, she faces the embarrassment of begging for medicines for her son: “He was shot and injured during a demonstration and the doctors said his leg would have to be amputated. Despite that, we only received $200 and were sent back home. I’ve already spent all of this money on a special bed and mattress, and on medication. Nobody came to ask about us afterwards.”

Gender-based violence (GBV)

In the context of already high levels of domestic violence, some participants reported that women are often victims of psychological and physical abuse by their husbands, who accuse them of responsibility for the injury of a son or daughter. One participant said: “My daughter was injured in a demonstration. Whenever my husband sees her bedridden or using crutches he tells me that it is my fault and that her future is ruined. This happens on a daily basis. My daughter and I are in a very bad psychological state.”

A study published by UN Women in December 2017 indicated that the absence of economic opportunities for breadwinners and their households are central drivers of GBV in Gaza. Poverty is also linked to overcrowding, with women survivors often citing living in the extended family households of their spouses as compounding their abuse. Factors that enable situations of abuse to continue include the fact that perpetrators rarely (if ever) face legal, criminal or social penalties for their behaviour; violence against women in the context of marriage is not considered a crime in civil law and relevant family law in Gaza; and dominant social norms prioritize the preservation of a marriage regardless of the cost to victims.

Gender mainstreaming: a priority for humanitarian programming in 2019

As reflected in the 2019 HRP, gender mainstreaming remains a priority for the OPT humanitarian community. Partners are committed to delivering a response that is sensitive and appropriate to the distinct needs and vulnerabilities of persons of different genders and ages. The full roll-out of a new and better Gender and Age Marker (GAM) in the 2019 planning cycle reaffirms the commitment to gender mainstreaming as a means to ensure the highest quality humanitarian programming in line with international standards. The GAM strengthens the previous tool by including age (in addition to gender) and, most significantly, by adding a monitoring component. In addition to measuring programme effectiveness, it is a valuable teaching and self-monitoring tool that allows organizations to learn by developing programmes that respond to all aspects of diversity. In 2019, the Humanitarian Gender Group, co-chaired by UN Women and OCHA, will continue to ensure gender and age mainstreaming in cluster-specific needs analysis, response planning, implementation and monitoring.

Four projects addressing GBV in Gaza supported by the Humanitarian Fund

During 2018, the OPT Humanitarian Fund (HF) funded four projects addressing gender-based violence (GBV) in the Gaza Strip. The projects, worth $1.02 million, are implemented by two national and two international NGOs for periods that range between seven and 11 months, starting from March 2018. The projects target more than 23,000 beneficiaries, of whom 61 per cent are women, 16 per cent girls, 16 per cent men and 7 per cent boys. Common to the four projects is the goal of promoting and strengthening protection mechanisms for vulnerable women and girls who are survivors of GBV or are otherwise affected by violence by providing appropriate responses for their psychosocial and health needs. The OPT HF is a pooled fund managed by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Coordinator. In 2018 the HF allocated a total of $21.2 million from contributions made by ten member states to support 52 projects across the Gaza Strip and West Bank.