Humanitarian operations undermined by delegitimization, access restrictions, and administrative constraints

Attempts to delegitimize humanitarian and human rights organizations operating in the OPT, particularly NGOs, have been on the rise in recent years. This has a negative impact on the ability of these organisations to deliver assistance and advocate on behalf of Palestinian rights. The situation is further compounded by longstanding access restrictions imposed on humanitarian staff and operations, restrictive legislation and attacks on human rights defenders. The shrinking of the operational space available for humanitarian work as a result of these pressures has contributed to the reduction of the 2019 humanitarian appeal for the OPT (see previous article).

The bulk of the delegitimization attempts have been advanced by a network of Israeli civil society groups and some associated organizations elsewhere, with the apparent support of the Israeli government. Targeted defamation and smear campaigns allege violations of counter-terrorism legislation and international law, or political action against Israel.

Most of these allegations are baseless or misrepresent and distort critical factual or legal elements. Humanitarian organizations operating in the OPT adhere strictly to the principles of neutrality, impartiality, independence and humanity, and implement rigorous UN, donor and internal standards to ensure compliance with these principles, and all relevant bodies of law. Donor governments additionally impose guidelines that reflect political sensitivities in the OPT context.

Accusations being made against humanitarian organizations operating in the OPT have resulted in a range of negative impacts. These include the allocation of time and resources to address allegations; some donors defunding certain activities to avoid risks; impediments by Israeli banks to the transferring of funds and procedures to close down accounts; refusal of Israeli venues to host events involving certain NGOs; and the potential undermining of information disseminated by organizations whose reputation has been damaged.

As stated by Jamie McGoldrick, the OPT Humanitarian Coordinator, on the occasion of the launching of the 2019 Humanitarian Response Plan: “We don’t mind as humanitarians any type of scrutiny, but it has to be evidence-based. Any scrutiny or auditing is meant to improve performance but in this case it is meant to block our performance, […] When reputable organizations with proven records of delivering critical humanitarian assistance in line with international humanitarian principles, and in line with donor scrutiny, are attacked, the authorities and donors must assist us in pushing back to ensure that the space is there to deliver the assistance”.

Severe impact on international NGOs

Between October and November 2018, the Association of International Development Agencies (AIDA), which represents the majority of international NGO and non-profit organizations operating in the OPT, conducted a survey among its member organizations to assess the impact of delegitimization. Just over half of AIDA’s members (41 of 80) responded to the survey.

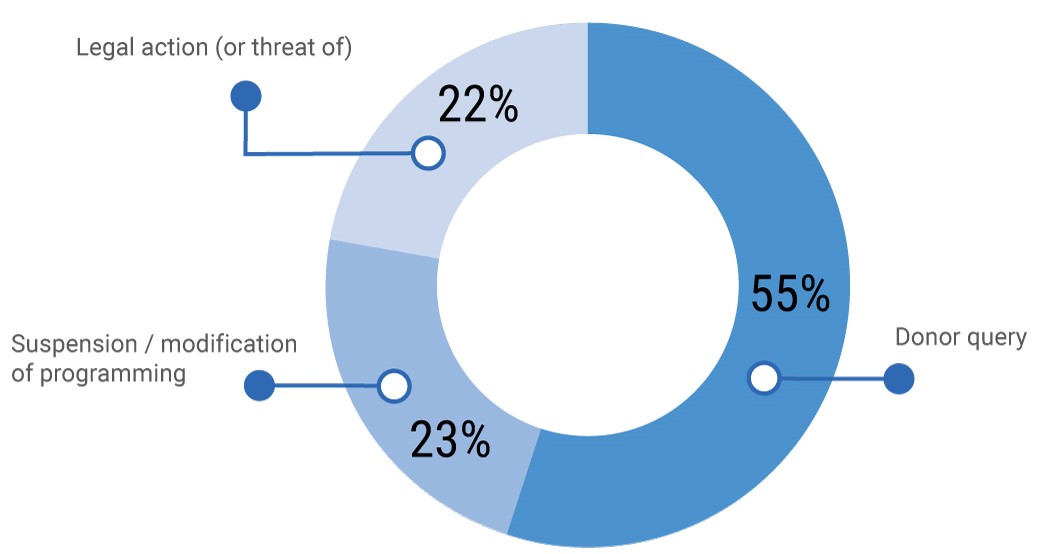

All of the organizations surveyed indicated that they had been affected in one way or another by the delegitimization campaign: 23 per cent reported that accusations had forced them to alter, suspend or terminate existing programmes, in part or in full; 22 per cent said they had faced threats of, or actual, legal or administrative actions against them; and 55 per cent reported that they had to answer additional donor queries about their programming. Overall, 43 per cent of the surveyed organizations indicated that the campaign had undermined their funding for certain types of activities.

Percentage of affected INGOs by type of impact

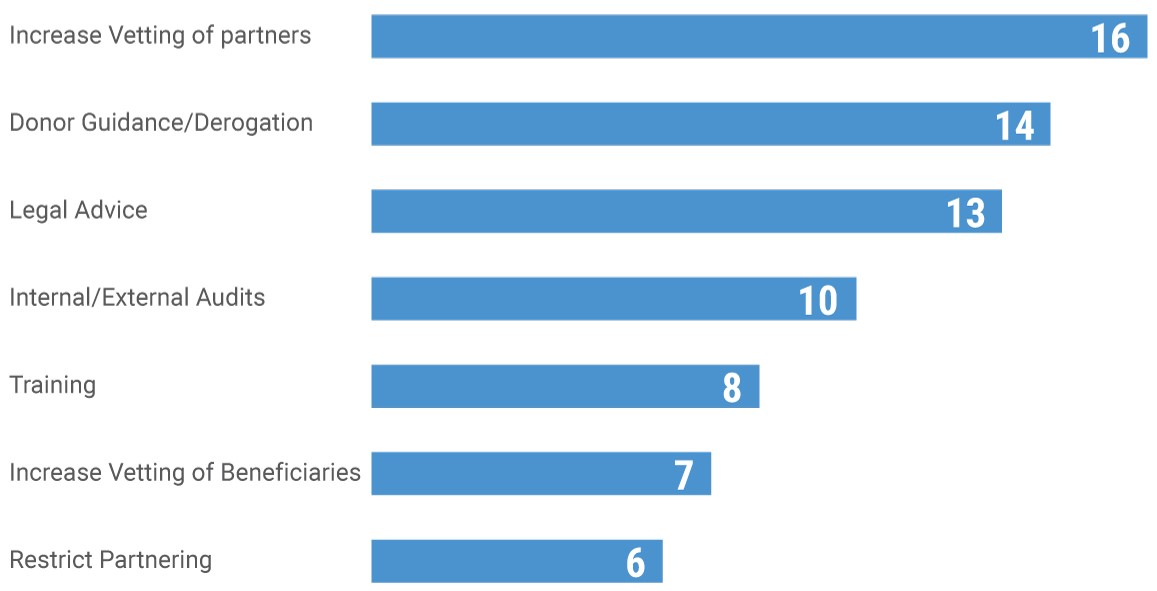

Coping strategies undertaken to confront these challenges include more stringent donor guidance and oversight, increased vetting of partners and beneficiaries, increased resorting to legal advice, additional staff training, as well as extra internal and external audits (see chart below). Half of the organizations surveyed by AIDA reported that they have appointed dedicated policy and advocacy staff, while 38 per cent have appointed staff dedicated to comply with additional donor requirements or risk management. Those strategies have diverted resources that would have been otherwise channeled to the provision of assistance.

With 37 participating agencies and projects accounting for almost 30 per cent of the total requested in the 2019 HRP, international NGOs are significant actors in the delivery of humanitarian aid and protection across the OPT. As leads or co-leads of national clusters (e.g shelter and education), some of these organizations also play a pivotal role in the coordination of operations on behalf of the entire humanitarian community.

Coping measures by number of affected INGOs

Access restrictions undermining operational space

This campaign has further shrunk an operational space already constrained by a range of access restrictions. These include long standing restrictions imposed by Israeli authorities, citing security concerns, on the movement of national staff of humanitarian agencies within the OPT, especially to and from the Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem, along with lengthy interrogations of staff and instances of permit withdrawal.

Access in and out of Gaza, including areas near the perimeter fence, by humanitarian staff working with the UN or with NGOs is also impeded by demands made by the Hamas authorities. These include searches of UN vehicles, issuance of permits and security interviews of staff entering and exiting Gaza, prevention of humanitarian activities in certain geographical areas, and demands for information about staff and beneficiaries.

Humanitarian interventions in Gaza have also been affected by a range of import restrictions, particularly for goods Israel considers ‘dual use’ items. Entry of some such items, particularly those required for water and sanitation projects, has remained challenging despite facilitation efforts by Israel through the temporary Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism (GRM) introduced in 2014.[1]

In the West Bank, assistance to vulnerable communities in Area C and East Jerusalem is often destroyed or seized on the grounds of lack of a building permit.[2] Furthermore, access restrictions to areas where humanitarian interventions are needed, as well as delays at checkpoints, hamper the access of humanitarian aid workers and materials to areas of need.

New legislation and attacks on human rights defenders

Palestinian human rights organization have reported repeated threats and intimidation of their staff;[3] detention, summons and raids on their offices; confiscation of property/ equipment; and the denial of entry visas to the West Bank.[4]

Additionally, Israeli, Palestinian and international human rights organizations operating in the OPT have faced several Israeli laws and administrative decisions targeting their right to freedom of expression, the right to access funding, and public funding eligibility.[5] An amendment to the Entry into Israel Law has expanded the discretion accorded to the Israeli Ministry of Interior to deny entry into Israel and the West Bank to any non-citizen/resident on political grounds.[6]

Palestinian NGOs have also been affected by a new law on cybercrime adopted by decree by the Palestinian Authority that, according to some NGOs, limits freedom of expression and is used to arbitrarily detain defenders and activists challenging human rights violations committed by the PA.[7]

As recently pointed out by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, “legislation, both adopted and proposed, singles out human rights organizations for increased restrictions. Administrative constraints are placed on their operations. Sources of funding are undermined through campaigns to delegitimize organizations working for the rights of Palestinians. Human rights defenders are arrested and threatened, and groups including Israeli organisations as well as foreign Jewish organizations are being targeted for standing up for Palestinians’ human rights.”

[1] The GRM is an agreement between Israel, Palestine and the UN to facilitate the entry of construction material into Gaza, primarily with the view to advance reconstruction and recovery of the damage incurred during the conflict. Since then, the GRM has facilitated the entry into Gaza of more than three million tons of construction materials, almost 600 large-scale projects have been completed and nearly 140,000 beneficiaries have been able to access material to repair, reconstruct or build new houses.

[2] See for example, OCHA, West Bank demolitions and displacement, November 2018.

[3] See “UN rights experts denounce Israel’s growing constraints on human rights defenders”, 3 March 2017. Palestinian Non-Governmental Organizations Network, “Attacks on Palestinian civil society organizations in occupied East Jerusalem: A Matter of Illegal Annexation and of Repression of the Right to Self-determination”, June 2018.

[4] According to a 2018 survey conducted by Palestinian Non-Governmental Organizations Network (PNGO) filled by 25 Palestinian NGOs operating in East Jerusalem, 20% of Organizations had travel bans for work abroad on their staff, and 12% were had a temporary ban or deportation from Jerusalem order. Due to Israel’s denial of visa to supporters from abroad, 48% of organizations had difficulty recruiting/ keeping foreign staff and 24% were forced to cancel activities with visitors from abroad.

[5] These include the so-called Nakba Law (2011), the Boycott Law (2011), the amendment to the Public Education Law (2018), and the Loyalty in Culture bill. Administrative decisions include the cancellation of leases or suspension of funding to institutions who perform, plan or host events or performances of which the authorities disapprove.

[6] Amendment No. 28 to the Entry into Israel Law stipulates that the Minister of Interior will not issue an Israeli entry visa to anyone who is not a citizen or resident of the country and who has issued a public call to boycott Israel or has undertaken to participate in such a boycott, including a boycott of the settlements.

[7] Position Paper on the Ongoing Campaign to Silence, Delegitimize, and De-fund Palestinian Civil Society Organizations and Human Rights Defenders, published by PHROC and PNGO, March 2018.