The humanitarian impact of the internal Palestinian divide on the Gaza Strip | June 2017

Key Facts:

- In June 2007, following hostilities between Fatah and Hamas, the latter took control of the Gaza Strip, starting a divide between the West Bank-based Palestinian Authority (PA) and the de-facto Hamas authorities in Gaza, which still continues.

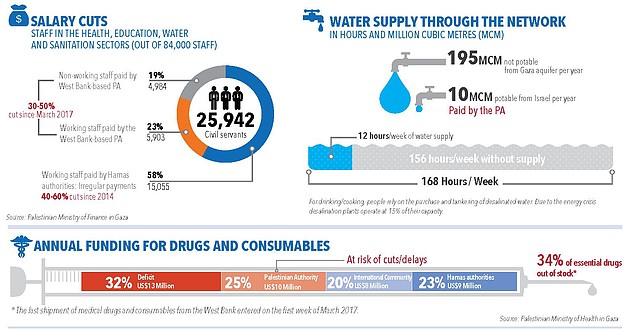

- Since 2014, all of the 22,000 civil servants recruited by the Hamas authorities have received less than half of their salaries, on an irregular basis. The other 62,000 staff in Gaza, who are on the PA’s payroll, had their salaries cut by 30-50% since March 2017.

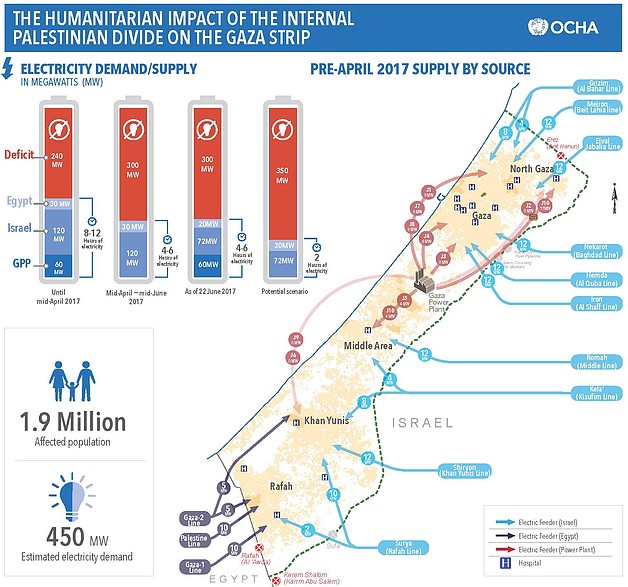

- Due to internal disputes regarding the funding and taxation of fuel for the Gaza Power Plant (GPP), in April 2017 the plant shut down, but resumed partial operations in late June, on the basis of fuel purchased from Egypt.

- In May 2017, the PA decided to cut its payments for the electricity that Israel provides to Gaza; in June, Israel reduced its supply by 40%.

- As of 22 June, households and service providers in Gaza receive 4-6 hours of electricity a day.

- 186 critical facilities providing health, water and sanitation, and solid waste collection services are being supported by emergency fuel delivered by the UN; reserves are expected to last until October 2017.

- Due to delays in shipments from the West Bank and longstanding funding gaps, 34% of essential drugs at the Central Drug Store in Gaza are out of stock.

- The referral of over 1,400 patients to medical treatment outside Gaza has been disrupted since March 2017, following the PA’s apparent suspension of its payments for this service.

- Most families in Gaza only receive piped water for 6-8 hours, once every four days, due to insufficient power supply; desalination plants are functioning at 15% of their capacity.

- Over 108 million litres of almost totally untreated sewage are being discharged into the Mediterranean every day due to electricity and fuel shortages. l The Palestinian Civil Defense in Gaza, in charge of rescue operations during emergencies, can operate at less than 45% of its normal capacity, due to critical shortages in staff and equipment, partially due to PA budget cuts.

- The split of the Palestinian civil service has reduced the capacity of local institutions in Gaza to deliver basic services, to respond to emergencies and to enforce the rule of law, increasing the hardship of the population. In the aftermath of the 2007 takeover, thousands of public employees in Gaza were forced by the PA to stop working, but continued receiving their salaries. Those subsequently recruited by the Hamas authorities have not received regular salaries since 2014, while those paid by the PA have recently had their salaries cut. The absenteeism as a result of the salary crisis has been compounded by the underfunding of the Gaza-based ministries, the duplication of functions and the lack of clear reporting lines.

- Disputes over the funding and taxation of fuel, as well as over the collection of payments from electricity consumers, have undermined the functioning of Gaza’s sole power plant (GPP) and led to its recurrent shutdown. To cope with the long blackouts, service providers are resorting to back-up generators, which depend on the availability of fuel and are not designed for uninterrupted use. Import of new generators and spare parts is restricted by Israel. The recent decision by the PA to reduce payments for Israeli-supplied electricity has aggravated the crisis significantly.

- Medical services in Gaza have been severely affected by the electricity cuts and the reduction in the budget allocated by the PA Ministry of Health. To cope with the lack of power, hospitals are postponing elective surgeries, discharging patients prematurely, and reducing cleaning and sterilizing of medical facilities. Patients’ long-term health is also threatened by delays in the shipment of essential drugs and disposables from the West Bank, and the disruption in the referral of patients to medical treatment outside Gaza. The financial crisis and the lack of training opportunities due to the blockade have also led to shortages in skilled personnel, especially anesthesiologists, surgical nurses and technicians.

- The shortage of power and of fuel to operate water and wastewater treatment facilities has reduced access to water and increased the risk of waterborne diseases. The limited operation of water pumps and water desalination plants has led to a decline in water consumption and hygiene standards. The shortening or suspension of sewage treatment cycles has led to the increased pollution of the sea along Gaza’s coast. Additionally, there is a constant risk of backflow of sewage onto streets, which may lead to flooding, displacement, and waterborne diseases.

- Following the Hamas takeover, key donors reduced and/or conditioned their funding for humanitarian and development projects in Gaza. This contributed to the channeling of assistance towards areas and institutions free of Hamas control, rather than to where assistance is most needed. Restrictions stemming from counter-terrorism legislation in their countries of origin, along with the “no contact” policy with Hamas imposed by some donors, have further restricted the operational space of international NGOs in Gaza.