Demolition and seizure of service infrastructure in Palestinian communities in Area C exacerbates risk of forcible transfer

The targeting of key service infrastructure in already vulnerable communities in Area C in recent months has exacerbated the coercive environment and places residents at risk of forcible transfer. In August, on the eve of the new school year, the Israeli authorities requisitioned nine educational-related structures serving 170 children in three such communities.

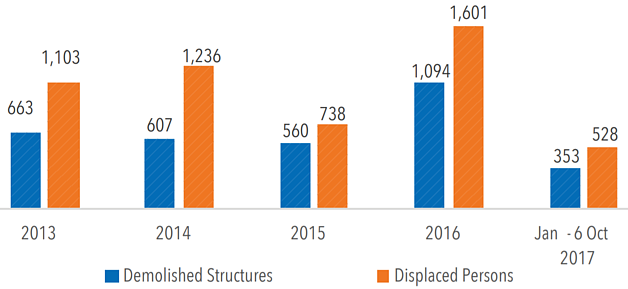

There has been an overall decline in the number of demolitions and seizures since the beginning of 2017 compared with the record peaks in 2016 and levels have returned to those documented in Area C previous years. In East Jerusalem, demolitions have continued at nearly the same rates recorded in 2016, which were the highest figures since 2000.

During August and September 2017, the Israeli authorities demolished and/or seized a total of 63 Palestinian-owned structures, displacing 88 people and otherwise affecting over 1,200. Of these, 40 structures were in Area C and 18 in East Jerusalem, all on grounds of lack of Israeli-issued permits which are nearly impossible to obtain. The remaining five structures were located in Deir Abu Masha’al, Kobar and Silwad villages, in Area B of Ramallah governorate, and were the family homes of the perpetrators/suspected perpetrators of attacks carried out in 2017 against Israeli forces and settlers.

The educational-related structures seized in August included six caravans for use as classrooms in Jubbet ad Dhib in Bethlehem governorate (see case study), plus a new kindergarten and two solar panel systems in the Jabal al Baba and Abu Nuwar communities in Jerusalem governorate.

The latter two communities are among the 46 Palestinian Bedouin communities in the central West Bank believed to be at heightened risk of forcible transfer due to a “relocation” plan advanced by the Israeli authorities. In August 2017, OCHA published the findings of an assessment of these communities to map vulnerabilities and quantify sectoral needs (see Bedouin communities box).

All but one of the educational-related structures referred to, plus another six structures, had been funded by international donors as humanitarian assistance. This brings the number of donor-funded structures demolished or seized since the beginning of 2017 to 95, constituting 29 per cent of all structures targeted during this period (roughly the same as in 2016).

According to the Palestinian Authority Ministry of Education, there are at least 50 Palestinian schools in Area C with demolition or stop-work orders pending by the Israeli authorities. A comprehensive Vulnerability Profiling Project (VPP) carried out in 2013 by humanitarian partners found that 36 per cent of the residential areas in Area C (189 of 532) lacked a primary school within the community; in 31 of these cases it was reported that children had to cross military checkpoints to reach school, and in 29 communities they faced settler harassment in their way to school.

Anecdotal evidence indicates that the shortage of school infrastructure in Area C communities, along with constraints to access to schools outside these communities, has had a range of negative impacts. These include an increase in early dropout rates, especially for girls, and moving children to live with host families closer to their schools.

Bedouin communities at risk of forcible transfer: a vulnerability profile

In May 2017, OCHA carried out a profiling survey of the 46 Palestinian Bedouin/herding communities in the central West Bank considered to be at high risk of forcible transfer. The survey, based on key informant interviews, found that there are over 8,100 people currently living in these communities who are affected to various degrees by a range of vulnerabilities. Over 70% of residents are Palestine refugees registered with UNRWA and about 80% are women and children. In terms of access to services:

- 20 communities lack any arrangement or public transportation system for their children to reach school, located up to six km from their homes;

- 18 communities are not served by mobile health clinics, and more than half are up to nine km away from the closest primary healthcare facility;

- 19 communities depend on tankering as a main water source, of which 10 communities pay more than 20 NIS per cubic meter, over four times the price of piped water;

- 25 communities rely on solar panels as the only or main source of electricity. These are at risk of requisition without prior warning. Half of the communities still rely on gas, kerosene and/or batteries as their first or second main source of electricity.

Thirty-six of the communities have witnessed demolitions over the past nine years and 57 per cent of households reported having at least one demolition or stop-work order pending against their homes or livelihood structures.

The entire OCHA data set is available in a fully searchable online dashboard, divided into several thematic sections.

The case of Jubbet Ad Dhib

Latest developments: In late September, the Israeli authorities returned the requisitioned solar panels and equipment to the community, and the system was subsequently reconnected. This followed a demand made by the Netherlands, as well as a petition against the requisition filed with the Israeli High Court of Justice by the village council and the implementing NGO.

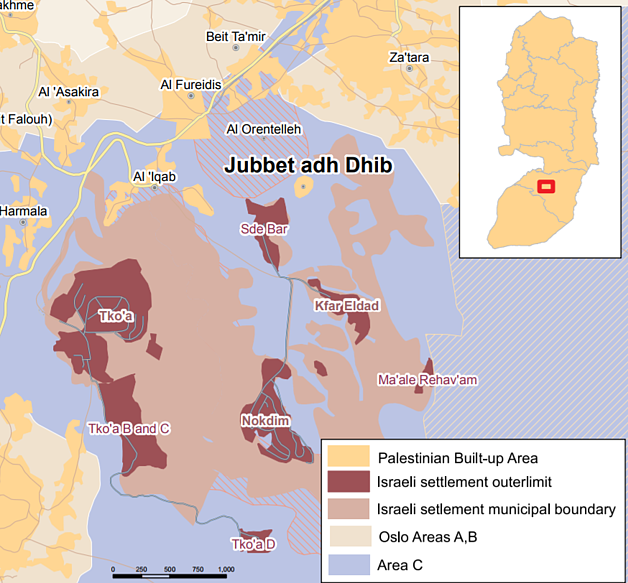

Jubbet Ad Dhib, approximately 160 people, in eastern Bethlehem governorate is a typical Area C community. Some of its residents reported that the community has existed in this location since at least 1929.

Employment in Israel and Israeli settlements, mostly in construction, is the main source of employment for most men in the community. Intensive settlement expansion, accompanied by intimidation and restrictions on access to land, have undermined herding and farming activities which were traditionally the main source of livelihood.

Within a radius of three kilometres from Jubbet Ad Dhib, there are two official settlements: Teqo’a and Noqedim. These have expanded into six nearby sites where unauthorized settlement outposts have been established without permits or formal approval by the Israeli authorities (Teqo’a B, C and D, Ma’ale Rehav’am, Kfar Eldad and Sde Bar). In recent years the authorities have either “legalized” these settlements by retroactively approving a planning scheme or are in the process of so doing.

By contrast, the Israeli authorities have refrained from issuing a planning scheme for Jubbet Ad Dhib, making it impossible for its residents to obtain building permits for their homes, livelihoods or service infrastructure. This has inhibited development and placed structures at risk of demolition or requisition. A draft outline plan for the community prepared by the PA Ministry of Local Government and submitted to the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA) in August 2012, is still pending approval.

While the community is connected to the water network operated by the Israeli Water Company -Mekorot, several requests submitted to the ICA since the 1980s to connect to the electricity grid were rejected on grounds that the community lacks a planning scheme. As a result, residents rely on a shared generator provided by the PA that supplies them with only 2-3 hours of electricity a day at a cost of 150 NIS per month per family. The inability to build in the village, combined with restrictions on access to land and services, have pushed the young couples in the village to leave over the past years according to the village council.[12]

To address this situation, in November 2016, an Israeli-Palestinian NGO, in partnership with the local Women’s Charitable Organization and with funding from the Netherlands, installed an off-grid solar panel system to provide electricity to 31 households, a mobile clinic, a mosque, a kindergarten and 5 workshops. On 28 June 2017, without any order or prior warning, Israeli forces raided the community and seized all 96 solar panels and related equipment, causing significant damage to some of the items.

Jubbet Ad Dhib also lacked a primary school. This required some 60 children to attend a school in the nearby town of Beit Ta’amar. In August 2017, an international NGO installed six caravans to serve as classrooms for a new school to be run by the PA Ministry of Education. A few days later, also without prior warning, Israeli forces dismantled and seized the caravans. Between 8 and 10 September, the residents of Jubbet Ad Dhib, and the villages of Beit Ta’mar and Za’tara, with PA support, built a concrete structure to replace the caravans, where the 60 children from Jubbet Ad Dhib and other children from the surrounding communities have enrolled and started the new school year.

[12] OCHA Special Focus, Displacement and insecurity in Area C of the West Bank, Aug 2011.