Concern about collective punishment: new measures targeting the residency rights of East Jerusalem Palestinians

Following a rise in Palestinian attacks since October 2015, and citing the need for deterrence and prevention, the Israeli authorities have implemented measures that penalize Palestinians for acts that they did not commit and for which they are not criminally responsible. These measures include the destruction of the family homes of Palestinians who carried out an attack or are suspected of carrying out or planning attacks, and the closure of localities where some of these suspects lived.[1] These practices raise concerns about collective punishment, which is prohibited under Article 33 of the Fourth Geneva Convention.

In recent months, the Israeli authorities have been targeting the residency rights of family members of suspected perpetrators who live in East Jerusalem, placing these family members at risk of forcible transfer as a result.

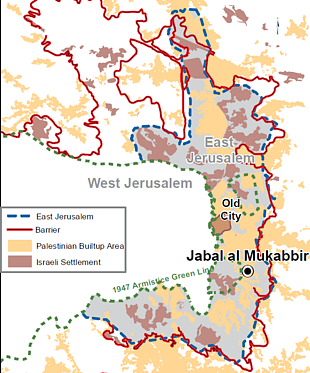

On 8 January 2017, a Palestinian man from the Jabal al Mukkaber neighbourhood of East Jerusalem carried out a ramming attack near his home, killing four Israeli soldiers and injuring another 15 participating in an educational tour; the perpetrator was shot and killed during the attack. The next day, thirteen members of his family (the Al Qunbar family) received notices of proceedings to revoke their residency in East Jerusalem, including residency permits received as part of a “family unification” process.[2] Announcing the decision to the media, the Israeli Minister of Interior said: “Let it be known to all who are considering carrying out an attack that their families will pay a heavy price for their actions and the consequences will be severe and far-reaching.”

On 8 January 2017, a Palestinian man from the Jabal al Mukkaber neighbourhood of East Jerusalem carried out a ramming attack near his home, killing four Israeli soldiers and injuring another 15 participating in an educational tour; the perpetrator was shot and killed during the attack. The next day, thirteen members of his family (the Al Qunbar family) received notices of proceedings to revoke their residency in East Jerusalem, including residency permits received as part of a “family unification” process.[2] Announcing the decision to the media, the Israeli Minister of Interior said: “Let it be known to all who are considering carrying out an attack that their families will pay a heavy price for their actions and the consequences will be severe and far-reaching.”

Eleven of the family members had their residency status in East Jerusalem revoked on 25 January 2017 under Section 11(a)(2) of the Entry into Israel Law. Two were spared, apparently because they are children. Although the stated rationale for the revocation was suspicion of connections with ISIS and involvement in terror activity,[3] the timing of the action and the statement of the Minister raise concerns that this may be a measure of collective punishment.

Eleven other members of the Al Qunbar extended family fear that the renewal of their “military family unification permits” has been delayed due to the attack. These documents, which allow them to live in Jerusalem, expired on 5 March 2017 and had not been extended over two weeks later when they met with the UN OHCHR. The immediate family of the attacker – his wife and four children – were also subjected to collective punishment and forced eviction when their family home was punitively sealed on 22 March.

Residents of Jabal al Mukabber (total population about 24,000) have experienced six punitive demolitions and house sealing since 2015, which displaced 10 households: 53 Palestinians, including 30 children.[4] These demolitions were carried out in connection to five attacks perpetrated by residents of the neighbourhood in which 14 Israelis (including four soldiers and one policeman) were killed and 40 Israelis were injured (including 15 soldiers and one policeman).[5]

The scope of the measures adopted following the January 2017 attack appear to be broader than in the past and affect a large number of extended family members and neighbours. Between 9 and 16 January, approximately 240 households living in 80 buildings received notices from the Jerusalem Municipality for planning and zoning violations that put them at risk of demolitions and forced evictions.[6] OCHA also documented twelve non-residential structures demolished on the grounds of the lack of a building permit. Although this is not the first time that municipal authorities have taken such action in the neighbourhood, the intensity and extent of the measures surprised the residents. Seen in the context of the January attack and the municipality’s action, it raises concerns that these were meant to punish the broader population.

The Israeli Supreme Court has previously permitted punitive demolitions but has not yet ruled on the constitutionality of punitive residency revocations. These punitive measures remain under challenge in the Court since 2006.[7] Regardless of the position under Israeli law, all forms of collective punishment are unlawful under international humanitarian law (IHL) and also violate a range of human rights, including the right to equal protection before the law and the presumption of innocence.[8] The specific practice of residency revocation may further result in violation of the prohibition on forcible transfers under Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention.

The case of Menwah Al Qunbar

One of those whose East Jerusalem residency was revoked was 64-year-old Menwah Ahmad Hamdan Al Qunbar, the mother of the attacker Fadi Al Qunbar. She had acquired permanent residency status in 1988 after a family unification process following her marriage to r East Jerusalem husband in 1981. The day after the attack, the Israeli authorities served Menwah a notice of a hearing at the Ministry of Interior about her residency status.

Menwah told UN OHCHR that she attended the hearing on 18 January with her lawyer, her husband and another son. Although the notice to her was on the grounds that her marriage was bigamous and her residency was received on the basis of false information, she said that this was not the focus of the hearing. Instead, the discussion was about her son and the attack he had carried out, and whether she supported his action. This again raises questions about the rationale of the action against her and other family members.

Despite the serious nature of the criminal allegations against them (connections with ISIS and involvement in terror activity), neither Menwah nor the other Al Qunbar family members appear to have been charged or arrested on those grounds. They continue to live in the neighbourhood but face the risk of forcible transfer if their appeals against the revocation are unsuccessful.[9]

The forcible transfer of another Jabal al Mukkaber resident, Nadia Abu Jamal – whose husband killed 6 Israelis in an attack in November 2014 – illustrates the devastating impact such measures have on Palestinians. Nadia Abu Jamal’s application for family unification was cancelled after the attack and the Israeli Supreme Court upheld the revocation of her residency status in July 2015. Her family house was punitively demolished in October 2015. Forced to move out, she currently lives in a West Bank village beyond the Barrier, separated from her four children who continue to live with their grandparents in Jabal al Mukabber.

OHCHR spoke with Menwah Al Qunbar again after her son’s house was punitively sealed in March. Despite the risk of her being forcibly transferred, she was more worried about her family: “I am afraid I will be disconnected from my children and grandchildren. My husband cannot sleep at night because of worry and anxiety. He does not know what will happen to us. I have to hold myself firm and strong to strengthen him.”

* This article was contributed by Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights.

[1] The UN Secretary-General recently expressed concern regarding such practices, confirming that they may amount to prohibited collective punishment. A/HRC/31/40 paras 29-33, 16 March 2017; A/HRC/34/36 paras 31-33; A/71/364 paras 25-26, 16 March 2017.

[2] East Jerusalem ID holders who marry persons carrying a West Bank or Gaza ID must apply to the Israeli Interior Ministry for family unification on their behalf if they wish to live together in East Jerusalem. In 2002, Israel froze applications for family unifications, and a year later it enshrined the freeze in the Nationality and Entry into Israel Law (Temporary Order). The Law was amended in 2005, making women aged over 25 and men over 35 eligible for military family unification permits to live with their spouses in East Jerusalem. An additional amendment from 2007 allows certain cases outside the eligible category above to be reviewed by a committee and to be considered for family unification based on ‘exceptional humanitarian grounds.’

[3] Letter dated 25/01/17 by Population and Immigration Authority.

[4] This is in addition to 36 demolitions and self-demolition incidents carried out on the grounds of lack of building permits that displaced 44 people and otherwise affected 46 others during the same period (2015 – Jan 2017).

[5] OCHA Protection of Civilians Database.

[6] Initial mapping of affected people by UN OCHA, January 2017.

[7] HCJ 7803/06. Four Palestinians from East Jerusalem were forcibly transferred to the West Bank after their residency was revoked on the grounds of lack of allegiance due to their alleged association with Hamas. See also A/67/372, para 39.

[8] Article 14, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Depending on the form of punishment, more rights may be violated. E.g. punitive demolitions lead to violations of the right to adequate housing and prohibitions on forced eviction (Art. 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. See also Articles 6, 7, 9 and 16, ICCPR).

[9] Article 47, Fourth Geneva Convention (GC IV). Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem are protected persons under international humanitarian law, despite Israel’s unlawful annexation of the city.