Barrier construction in Bethlehem resumes

Negative impact on access to livelihoods and services

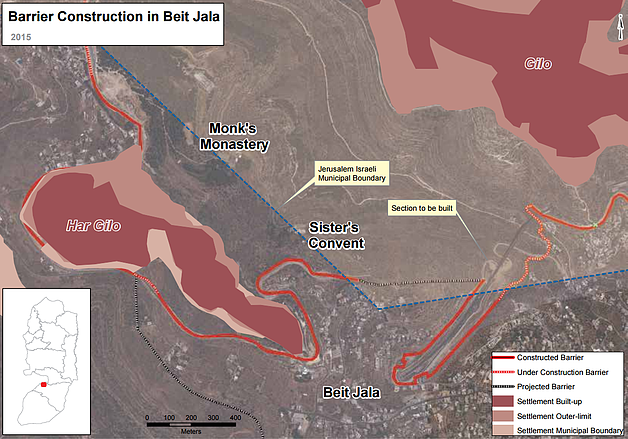

On 17 August, the Israeli authorities resumed construction of a section of the Barrier in the Cremisan valley extending from Beit Jala to the village of Al Walaja in Bethlehem governorate. Construction has resulted in the uprooting of ancient olive trees (see bellow) and the resumption of local protests. Based on previous experience in other West Bank areas, there is concern that agriculture-based livelihoods in the Cremisan area will be eroded.

Once complete, the Barrier will separate 58 Palestinian farming families from approximately 3,000 dunams of land planted with olive groves, fig and almond orchards, and the only recreational green space in the area surrounding the Cremisan monastery and convent. The Barrier may also impact the access of 450 children in the Bethlehem area to education provided by the local Salesian religious order: the institutions run by the Cremisan convent include a primary school (up to 8th grade), a kindergarten, and a school for children with learning difficulties.

The affected families have repeatedly challenged the route of the Barrier in the Cremisan area before the Israeli High Court of Justice (HCJ). The petitioners argue that the route will damage the fabric of their communities, will cause environmental damage to historic agricultural terraces, and contravenes international human rights and humanitarian law (see box herein). The petitioners also claim that the route was designed to bring Har Gilo settlement to the ‘Israeli’ side of the Barrier and connect it to Gilo settlement in East Jerusalem. Both settlements were constructed on land belonging to Bethlehem.

In April 2015, the HCJ issued its final decision requesting that the State of Israel consider alternative routes to ensure connectivity between the two religious institutions and between them and Bethlehem and Beit Jala. Later that month, the petitioners were informed that the Israeli authorities would start construction of a section of the Barrier, but would leave a small opening to ensure access to and from the monastery and convent. The Israeli Ministry of Defence has also committed to install an ‘agricultural gate’ in the Barrier to allow farmers access to their land. An appeal filed in June to halt construction was overturned.

According to the State: “The areas of the security fence which remain incomplete, such as the 1,500 meters of the Cremisan valley, are among the most sensitive areas between Israel and the West Bank from a security viewpoint, and are currently being exploited for infiltration by terrorist cells and criminal elements.”

At present, there are 85 agricultural gates along the length of the completed Barrier. Of these, only nine open daily and the majority (63) only open for a few weeks during the annual olive harvest. Farmers in approximately 150 communities with land isolated between the Barrier and the Green Line are obliged to apply for ‘prior coordination’ or obtain special permits to access their farming land and water resources through a designated gate. The limited allocation of access permits, together with the restricted number and opening times of the Barrier gates, continues to severely curtail agricultural practices and undermine rural livelihoods throughout the West Bank.

“My olive trees are worth more than money”

On the morning of 17 August, Issa al-Shatleh of Beit Jala was informed by a neighbour that the Israeli authorities were uprooting his olive trees. Some 30 olive trees, the majority of them hundreds of years old, were uprooted to make way for the route of the Barrier in the Cremisan area. “Each of these olive trees can yield 16 kilograms of good olive oil, enough for me and my four brothers. But it is more than the monetary value. These trees are hundreds of years old, planted by my ancestors. I have so many memories of both good and bad times associated with them since I was a boy.”

Although the trees were replanted by the Israeli authorities, Issa complains, “Look how close together they are. Some of them have been replanted on my neighbour’s land”. Asked if they will survive and bear fruit in the forthcoming olive harvest, he shrugs.

Issa’s land lies under the bridge that forms part of the rerouting of Road 60 in 1994 to enable settlers to travel between Jerusalem and Hebron and bypass Bethlehem. Part of his land was used by the excavators and bulldozers and trees were damaged. He also lost some trees in 2008 when another section of the Barrier was built in the area.

Issa says that he did not receive official notification from the Israeli authorities to inform him that his land was being requisitioned to build the Barrier. He also expressed concern about the proposed gate system that the Israeli authorities claim will guarantee him access to land soon to be isolated by the Barrier, given the experience of farmers in the rest of the West Bank. “This Wall is contrary to international law,” he insists, citing the International Court of Justice advisory opinion. He points to the nearby Gilo and Har Gilo settlements. “It’s all about the settlements.”

The International Court of Justice on the Barrier

On 9 July 2004, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued an advisory opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory. The ICJ recognized that Israel “has to face numerous indiscriminate and deadly acts of violence against its civilian population” and that it “has the right, and indeed the duty, to respond in order to protect the life of its citizens. [However], the measures taken are bound nonetheless to remain in conformity with applicable international law.”

The ICJ stated that the sections of the Barrier route which ran inside the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, violated Israel’s obligations under international law. The ICJ called on Israel to cease construction of the Barrier “including in and around East Jerusalem”; dismantle the sections already completed; and “repeal or render ineffective forthwith all legislative and regulatory acts relating thereto”.

The Court’s Advisory Opinion stated that UN member states should not recognize the illegal situation created by the Barrier and should ensure Israel’s compliance with international law. UN General Assembly Resolution ES- 10/15 of 20 July 2004 demanded that Israel comply with its legal obligations as stated in the ICJ opinion.