Approaching the tenth anniversary of the ICJ advisory opinion: Impact of the Barrier on agricultural productivity in the northern West Bank

On 9 July 2004, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued an advisory opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory. The ICJ recognized that Israel ‘has to face numerous indiscriminate and deadly acts of violence against its civilian population’ and that it ‘has the right, and indeed the duty, to respond in order to protect the life of its citizens. [However], the measures taken are bound nonetheless to remain in conformity with applicable international law.’

The ICJ stated that the sections of the Barrier route which ran inside the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, violated Israel’s obligations under international law. The ICJ called on Israel to cease construction of the Barrier ‘including in and around East Jerusalem’; dismantle the sections already completed; and ‘repeal or render ineffective forthwith all legislative and regulatory acts relating thereto’.

In the lead up to the tenth anniversary of the ICJ advisory opinion in July 2014, OCHA will issue a series of articles in the Humanitarian Bulletin to highlight the continuing humanitarian impact of the Barrier.

The Permit and Gate Regime

Since 2004 in the northern West Bank, Palestinians have been obliged to obtain permits from the Israeli authorities to access land between the Barrier and the Green Line: the ‘Seam Zone.’[1] To apply for or renew a permit, applicants must satisfy the security considerations necessary for all Israeli-issued permits and also submit valid ownership or land taxation documents to prove a ‘connection to the land’.[2] Although reliable data are difficult to obtain, the approval rate for Barrier permits for the whole of 2013 varied from approximately 33 per cent in Salfit governorate (590 out of 1,809 applications); 46 per cent in Tulkarm governorate (4,915 out of 10,630 applications); to 66 per cent in Qalqiliya governorate (9,935 out of 14,914 applications). These data are consistent with figures collected by OCHA over the last three years which show an approximately 50 percent rate of permit approval/rejection in the northern West Bank.[3]

For those farmers granted access to their land behind the Barrier, passage is channelled through a designated gate. Most Barrier crossings only open during the annual olive harvest and only for a limited amount of time during those days, prohibiting year-round access and cultivation. In total, there were 81 gates designated for agricultural access, as monitored, during the 2013 olive harvest. However, of these, only nine open daily; an additional nine open for some day(s) during the week; and the majority, 63, open during the olive season, an approximate 45-day period annually. In addition, there are restrictions on the vehicles and materials that farmers are allowed to take into the ‘Seam Zone.’ The limited opening hours also penalise the employed and ‘part time’ farmers who might otherwise assist in cultivating family holdings after work.

Impact on Cultivation

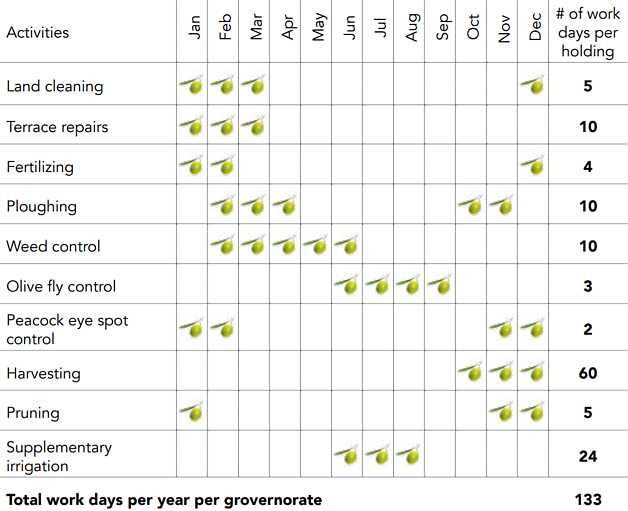

The limited allocation of permits and restricted number and opening times of the Barrier gates deprive farmers of making optimal use of the full agricultural cycle. This affects olive production in particular, which accounts for 25 per cent of the agricultural income of the oPt.[4] Many essential practices are related to the weather, the life cycle of trees, and outbreaks of pests and disease. Maintenance needs to be carried out at specific times of year, as illustrated in the accompanying table from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) based on a standard distribution of 12-16 trees per dunum. All of the practices play an important role in ensuring a high quality, profitable and relatively constant yield; delays or prevention of any of the activities may have an adverse impact on olive productivity and value.[5]

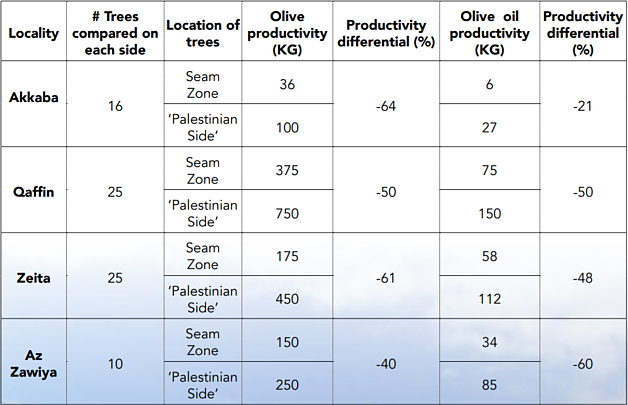

Data collected by OCHA in the northern West Bank since 2010 show that olive trees in the ‘Seam Zone’ have between 40 and 60 per cent reduction in yield compared to equivalent trees on the ‘Palestinian’ side of the Barrier, where the essential activities detailed by FAO can be carried out on a regular and planned basis. The study analyzed four comparable plots of land on both sides of the Barrier and measured their productivity in terms of both olive and olive oil output. The four olive tree plots located on the ‘Palestinian’ side of the Barrier were freely accessible to farmers throughout the year. However, farmers were only able to access the groves located in the ‘Seam Zone’ during the olive harvest in the case of Az Zawiya, and an additional two to three times a week in the other locations, provided that they had obtained a permit and subject to the conditions and constraints outlined above.

Calendar of major agricultural practices related to olive production

(based on an average holding of 10 dunums with 16 olive trees per dunum)[6]

Average productivity differential between trees on both sides of the Barrier (2013 season)

Note: the selection of the trees compared in the study relied on the following criteria:

- The same farmer owns olive groves on both sides of the Barrier.

- Plots were comparable in terms of topography and soil variety and were planted with the same variety of olive.

- The olive trees were approximately 50 years in age.

Tayseer ‘Amarneh, farmer, Akkaba, Tulkarm

“There are complicated procedures at the gates regarding the kind of agriculture materials and equipment we are allowed to take to our land behind the Barrier and this directly affects the quality and type of work that we can carry out. Many times, the soldiers at the gate refused to let me pass with my tractor when I needed it to work on our land; the same with agricultural tools, such as saws, which I need to prune my trees. They told me to go to the Palestinian DCO to coordinate to allow these materials to cross. When I wanted to carry fertilizer across, the soldiers told me to drop it on the ground for a security check and many times they refused to let it pass. Even saplings and plants need coordination before they are allowed to cross.”

Mohammed Saed Khatib, farmer Qaffin, Tulkarm

"Our land and trees have been badly affected by the Barrier and olive and olive oil productivity is decreasing year by year. This has affected my livelihood and our family’s financial situation. My children are good at school and I was planning to send them to university, but due to the decrease in earnings from our land, it will be difficult to make these dreams come true."

"Our land and trees have been badly affected by the Barrier and olive and olive oil productivity is decreasing year by year. This has affected my livelihood and our family’s financial situation. My children are good at school and I was planning to send them to university, but due to the decrease in earnings from our land, it will be difficult to make these dreams come true."

* Some inputs in this article were contributed by the UN Food and Agriculture organization (FAO)

[1] For the purposes of this report, the northern West Bank comprises the Jenin, Tulkarm, Qalqiliya and Salfit governorates. Of the 39 agricultural gates in the Barrier in these governorates, 35 are accessible by permits and four by ‘prior coordination’ with the Israeli District Coordination Liaison (DCL) Office.

[2] This requirement is particularly onerous given that only thirty-three percent of land in the West Bank has been formally registered and ownership is passed on by traditional methods which do not require formal inheritance documentation. See ‘Land Registration in the West Bank’ OCHA, Five Years after the International Court of Justice Advisory Opinion, p. 21.

[3] Farmers consistently complain that the distribution is irregular: some families have more than one permit holder, others have a single successful applicant - not necessarily the most able-bodied or appropriate, and many families receive no permit at all; traditionally, extended families participate in planting, harvesting and maintaining the land throughout the year. In addition, those who experience repeated refusal are discouraged from re-applying. The short validity of permits also results in farmers’ enforced inactivity in the period between the expiry of a current permit and its renewal or rejection.

[4] This includes the value of picked olives and processed olive oil (PCBS data, 2003-2010 averages).

[5] FAO, Overview of the Olive Sector in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, 13 October 2013. According to FAO, there are 40,000 dunums of olive trees belonging to 135 communities in the ‘Seam Zone’.

[6] Ibid.