Tightening of coercive environment on Bedouin communities around Ma’ale Adumim settlement

Since the beginning of 2017, a number of developments have generated additional pressure on Palestinian Bedouin communities located within and around the area designated by the Israeli authorities for the E1 settlement plan and the expansion of Ma’ale Adumim settlement in eastern Jerusalem governorate. The 18 communities in this area belong to a larger group of 46 Bedouin communities in the central West Bank, which the Israeli authorities seek to “relocate” to three designated sites.

The authorities have justified the plan claiming that the residents lack title over the land and/or building permits, and that the relocation will improve their safety and access to services. The residents, most of whom are registered refugees originally from what is now southern Israel, firmly oppose this plan and have requested protection and assistance in their current locations.

As stated by the UN Secretary-General, relocation may amount to a forcible transfer, a grave breach of the fourth Geneva Convention, even in the absence of direct physical force.[1] This is because the coercive environment imposed on these communities (including the destruction and threat of destruction of property, access restrictions, and denial of service infrastructure) prevents the achievement of genuine consent.

According to media reports, the Ministerial Committee for Legislative Affairs of the Israeli Cabinet recently held a series of discussions on a draft bill for the unilateral annexation of Ma’ale Adumim settlement to Israel. This is a preliminary step towards submission of the bill to the parliament for approval.[2]

Demolitions and displacement

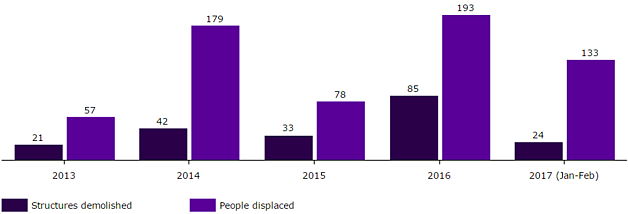

During the first two months of 2017, the Israeli authorities demolished a total of 24 homes and other structures in the 18 Bedouin communities in the affected area on the grounds of lack of Israeli-issued building permits. Since none of these communities has a planning scheme approved by the Israeli authorities, it is impossible for residents to obtain such permits.

Around half of the structures destroyed over the two-month period had been funded by donors, provided as humanitarian assistance. This resulted in the displacement of 133 people, more than half of them children. While most have remained on the same sites in very precarious conditions, others have temporarily moved in with relatives in nearby communities (see case study on Jabal al Baba).

The incidents follow a significant increase in demolitions and seizures in the area during 2016, in which a total of 85 structures were targeted compared with an average of 32 during the previous three years (2013-5). Ten per cent of all structures demolished in Area C during 2016 were located in this area compared with 6 per cent in the preceding three years. Between 2013 and 2016, approximately 180 structures were targeted in 13 of the 18 communities and over 500 people were displaced.[3]

Demolitions and displacement in Bedouin communities in and around the area of the E1 settlement plan

Khan al Ahmar

- Latest developments: On 5 March the ICA issued final demolitions orders to all structures in the community, which could be implemented as soon as 12 March

In the early hours of 19 February 2017, Israeli Civil Administration (ICA) officials, accompanied by a large group of army and police forces, distributed dozens of stop work orders in one of the affected communities: Khan al Ahmar - Abu Al Helu (around 140 people). The community leader told OCHA that during the incident, a senior ICA official informed him that they had no choice but to move to one of two “relocation sites” (Al Jabal or An Nuweimeh). Four days earlier, notices had also been received about a last chance to object to previous demolition orders on some additional structures in the community.

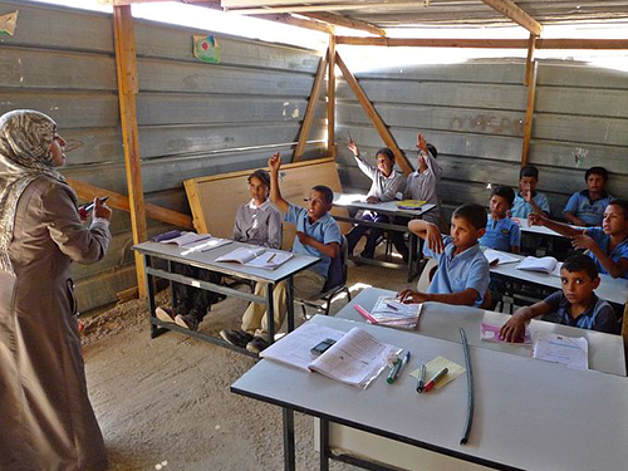

An initial assessment by OCHA indicates that all of the community’s structures (some 140) were included in the recent orders and notices. These include a donor-funded primary school built in 2009 with the support of an international NGO and run by the Palestinian Ministry of Education. The school currently serves around 170 children from five Palestinian Bedouin communities in the E1 area.

The rationale and legal implications of the recent orders remain unclear because nearly all of the structures have outstanding demolition or stop work orders issued in previous months or years. Most of them are covered by a temporary injunction issued by the Israeli Supreme Court that prevents the ICA from executing these orders.

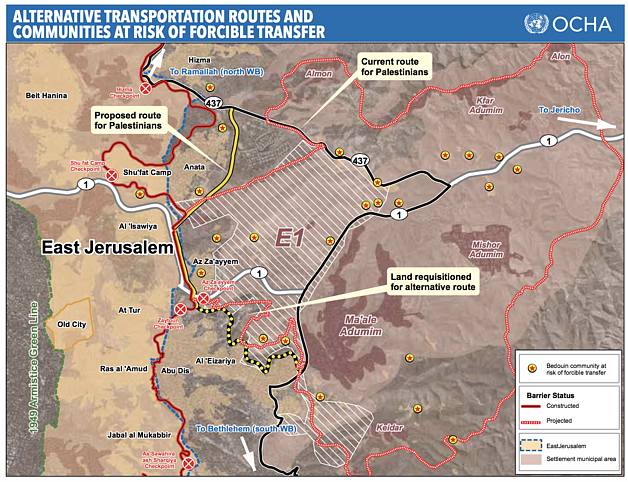

New “fabric of life” road

In December 2016, the Israeli authorities issued a military order requisitioning 415 dunums of land next to two of the affected communities: Wadi Jimel and Jabal al Baba, citing security reasons.[4] According to official information, the land will be used for the construction of a new road that will serve as the main route for all Palestinian traffic between the southern and central West Bank, and will connect to the northern section of this alternative route, which was completed several years ago but has not yet been opened (see map). The planned road would effectively divert Palestinian traffic from the current route running along Ma’ale Adumim settlement, making the latter for the almost exclusive use of Israeli settlers.[5]

As approved by the Israeli Cabinet in 2006, the Barrier will surround Ma’ale Adumim, along with the 18 Bedouin communities and a few adjacent settlements; this section of the Barrier has not yet been constructed. The new road, including the completed and planned sections, would not be included inside this area. Over the past decade, the Israeli authorities have built dozens of road sections (often made of tunnels, underpasses and sunken roads), reconnecting Palestinian areas that were cut off from each other by the Barrier, referring to these as “fabric of life” roads.

Although these roads have improved Palestinian access, they have also raised concerns about the seizure of land and destruction of property located along these routes, and their contribution to the fragmentation of the West Bank.

Community sources in Jabal al Baba and Al 'Eizariya told OCHA that during two of the demolition incidents that took place in January 2017, an ICA official indicated to them that their properties were being demolished because they were located along the route of the planned road. This road exacerbates the coercive environment experienced by some of the Bedouin communities at risk of transfer. Representatives of Al 'Eizariya municipality also raised concerns that the road will severely disrupt existing urban development plans for the town.

Jabal al Baba demolition

On 26 January 2017, the ICA, accompanied by the army, demolished six structures belonging to two households in Jabal al Baba, one of the 18 communities within the area allocated for the E1 plan. The demolition targeted three residential structures, two animal shelters and one outdoor toilet, on the grounds of lack of building permits.

On 15 February 2017, OCHA visited one of the two displaced families whose property and belongings were reduced to rubble. The demolition had targeted two residential units made of corrugated iron and wood, and a pen where they kept chicken, turkeys and ducks. According to the owner, Salem, the demolition took the family by surprise as they had a court injunction against it and had received no prior warning.

On 15 February 2017, OCHA visited one of the two displaced families whose property and belongings were reduced to rubble. The demolition had targeted two residential units made of corrugated iron and wood, and a pen where they kept chicken, turkeys and ducks. According to the owner, Salem, the demolition took the family by surprise as they had a court injunction against it and had received no prior warning.

Salem, his wife, Umm Muhammed, and four children are now homeless. Umm Muhammed, her two sons (aged 17 and 18) and two unmarried daughters (aged 23 and 24) are staying with Salem’s married brother in the neighbouring town of Al Eizariya. Salem is living close to his demolished house in an old Ford transit van converted into a makeshift home and covered with a tarpaulin to shelter from the rain and cold wind. The van’s back seats are the bedroom and sofa, and the side mirror is a peg for hanging clothes. The area outside the van’s side door serves as the living room and kitchen. It is small, muddy and chaotic, and can barely fit two chairs.

The family received basic humanitarian relief items, including two tents, but reported that they have not been able to put them up because of the wet ground, the wintery, windy conditions, and fear of demolition by the ICA and the army. This was the second time the family experienced a demolition since 2014. Salem said that after the first time round he was in a much better financial position and was able to rebuild his house. This time, he tried to make a temporary shelter out of car tyres but was unsuccessful.

Umm Muhammed, Salem’s wife, described the psychological and physical difficulties faced by the family. “The demolition has been devastating and our situation is miserable. We’re homeless. It’s been psychologically tiring for all of us. I personally feel powerless and unwell. Where shall we go? And how shall we live here? Our stuff is under the rubble. I have had to borrow clothes and shoes from my sister. The girls are very sad; they lost everything: the clothes they like and things they need. They do not feel comfortable or free at their uncle’s house, which is already crowded with his kids (over 13 of them) and two wives. They do not even feel comfortable to make a cup of tea there. Before the demolition, I loved keeping our house clean and tidy. Now look around. No one can live like this. I cannot understand how my husband can live in such conditions... I come to see him here (in the van) for a few hours every day. My daughters also come but cannot stay for long. There is nowhere to stay and nowhere to cook. There is no toilet or bath... Where we stay is not our home. I don’t feel comfortable and relaxed to cook. To demolish someone’s house is to wreck their life…,” said Umm Muhammed.

[1] See Report of the Secretary-General, A/HRC/31/43, 20 January 2016, para. 68.

[2] Jonatan Lis, After Trump-Netanyahu Meeting: New Push to Annex West Bank Settlement, Ha’aretz, 2 March 2017. According to this report, Prime Minister Netanyahu was keen to postpone a decision on this issue.

[3] Since some families had their home demolished more than once, the cumulative figure of people displaced includes cases of “double counting”.

[4] The order renews a previous order originally issued in 2007 but not executed. The current order is in force for three years, with an option for extension.

[5] This would be the second diversion of Palestinian traffic travelling between the northern and southern West Bank: following the 1993 “closure” imposed on the West Bank, Palestinian plated vehicles were banned from using the main route running through East Jerusalem.