Significant increase in risk of displacement in East Jerusalem

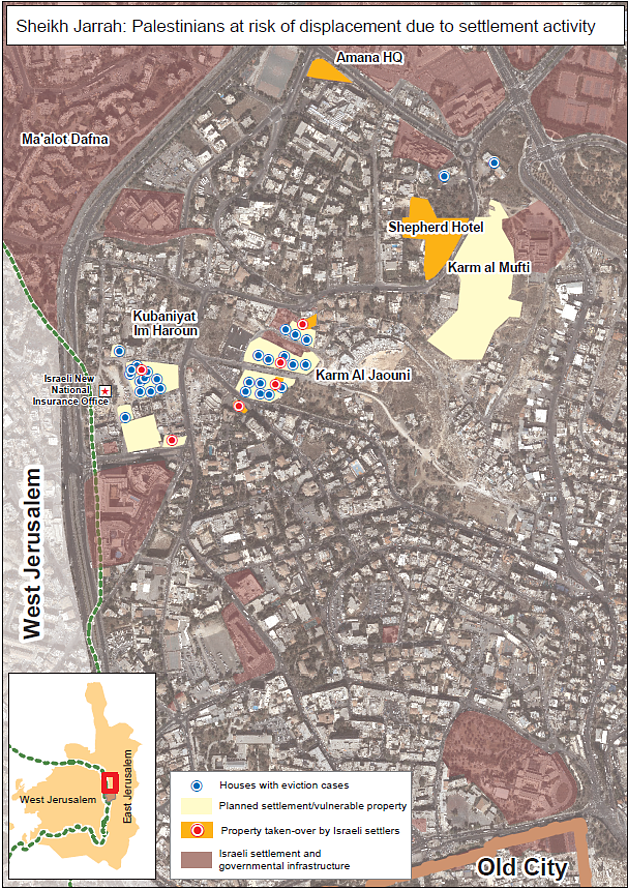

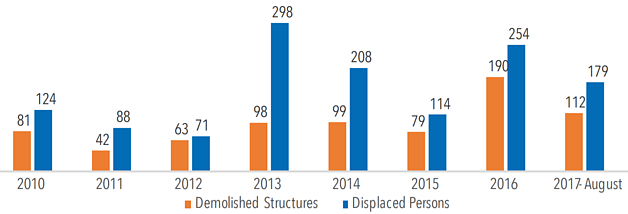

Recent developments in East Jerusalem highlight the coercive environment affecting many Palestinian residents of the city. Four recently-advanced settlement plans in Sheikh Jarrah neighbourhood threaten with eviction over 70 Palestinian residents. In total, at least 260 Palestinians living in 24 residential buildings in the area are under threat of eviction in cases brought against them by Israeli settler organizations, the General Custodian and/or Israeli individuals.[8] The number of demolitions of homes and other structures – another key pressure on Palestinians in East Jerusalem – is almost as high as in 2016, which saw the highest number of demolitions since 2000. In July, the Israeli Prime Minister gave his support to a plan that would absorb a number of West Bank settlements into the Jerusalem municipality while administratively separating Palestinian localities beyond the Barrier from the municipality, dramatically altering the city’s demographic composition.[9]

Whether as a result of a demolition or an eviction, displacement generates humanitarian need: it deprives people of their homes, disrupts their livelihoods and access to services, and often has a devastating psychosocial impact, particularly among children.

Settler activity in Palestinian residential areas

Israeli settlers are targeting densely populated Palestinian residential areas of East Jerusalem, in particular the Muslim and Christian quarters of the Old City, Silwan, Sheikh Jarrah, At-Tur (Mount of Olives), Wadi Joz, Ras al-Amud and Jabal Mukabbir. Over 3,000 Israeli settlers now reside in these areas, either in houses expropriated using the Absentee Property Law on the basis of alleged prior Jewish ownership, in buildings purchased from Palestinian owners, or in residences custom built and financed by settler organizations.[10] The impact on Palestinian areas includes restrictions on public space, residential growth and freedom of movement, along with increased friction and violence. In the most severe cases – in the Old City, Silwan and Sheikh Jarrah – settler expropriation has resulted in loss of property and the eviction of long-term Palestinian residents.

The Sheikh Jarrah residential neighbourhood is a key target for settlement activity owing to its strategic proximity to the 1949 Armistice Line (Green Line) and to the Old City. The area is already the site of a number of Israeli government institutions, including the police and border police headquarters, the Ministry of Justice, and the national insurance building, which is currently under construction. The Shepherd Hotel was expropriated by the Israeli authorities in 1967: the final stages of a new settlement is underway on the site. On another plot of land in Sheikh Jarrah an office building has been constructed for the Amana Association, a settler organization (See map).[11]

In late 2008 and 2009, more than 50 Palestinians, including 20 children, were forcibly evicted by the Israeli authorities from their homes in the Karm al Jaouni area of Sheikh Jarrah .[12] based on claims the properties had been owned by Jewish individuals or associations prior to 1948. A 1970 Israeli law acknowledges such claims despite the fact that Jews who lost their properties during 1948 received compensation and alternative housing, primarily in neighbourhoods previously inhabited by Palestinians. The law does not permit Palestinians who owned land or property in areas before 1948 that are now part of the State of Israel and were declared ‘absentees’ to regain their former possessions.

Following the eviction of the Palestinian residents, the homes were immediately handed over to settler groups that already occupy several other buildings in the area. As of 31 August, a total of 23 households comprising around 100 people (30% of them children) have eviction cases filed against them by Israeli settler organizations. The eviction proceedings, in which the families are named as defendants, are primarily based on alleged non-payment of outstanding rent, the building of extensions without the required building permits, and claims that the families are responsible for disturbances and threatening behaviour against their neighbours. According to plans submitted to the Jerusalem municipality, the settlers ultimately intend to demolish all properties in this area to make way for a new Israeli settlement.

Settler organizations have also targeted Kubaniyat Im Haroun in the west of Sheikh Jarrah. There has been an ongoing ownership dispute in this area between the Palestinian residents and the Israeli Custodian General[14] acting on behalf of Israeli individuals who claim to have owned the land before 1948, and other Jewish owners. The majority of Palestinians residents in this area refugees living in generally dilapidated conditions with more than one nuclear family living in each house. A protracted legal battle came to an end in September 2010 when the Israeli Supreme Court ruled in favour of the Custodian General and other Jewish individuals. Concurrently, individual eviction cases have been filed against 35 households in the area with a population of 140 people of whom more than a third are children

Settlement plans in Kubaniyat Im Haroun pose threat of further evictions

In July 2017, the Jerusalem Regional Planning Committee discussed plans for new settlement units, including four plans for the Kubaniyat Im Haroun neighbourhood. Two of the plans (14029 and 14151 for a three and five-storey building respectively) envisage the demolition of two residential buildings, placing 17 Palestinian households with 74 people at risk of displacement. There are also plans for a nine-storey building to house the Or Shameach Yeshiva campus (also known as the Glassman campus) and an additional six-storey office building. Although these plans target empty plots of land and do not entail evictions, they will further change the demographic character of the neighbourhood and create a contiguous belt of settlement units and Israeli government buildings throughout Sheikh Jarrah.

The eviction of the Shamasneh Family

The Shamasneh family have lived in their home in Kubaniyat Im Haroun since 1964 but have become the subject of eviction proceedings initiated by the Custodian General and the Israeli landowners. The family of eight, including one child, are at imminent risk of forced displacement, including 84-year-old Ayoub Samasneh and his 78-year-old wife. Between 1972 and 2009, the family paid annual rent to the Custodian General, but the latter then refused to renew the rental contract on the instructions of the heirs of the original Jewish landowner. Although some of the Palestinian families in Kubaniyat Im Haroun come under the provisions of the Protected Tenants Act 1972, the Israeli High Court has ruled that the Shamasneh family are not considered protected tenants and that their landlords are allowed to evict them.

The Shamasneh family have lived in their home in Kubaniyat Im Haroun since 1964 but have become the subject of eviction proceedings initiated by the Custodian General and the Israeli landowners. The family of eight, including one child, are at imminent risk of forced displacement, including 84-year-old Ayoub Samasneh and his 78-year-old wife. Between 1972 and 2009, the family paid annual rent to the Custodian General, but the latter then refused to renew the rental contract on the instructions of the heirs of the original Jewish landowner. Although some of the Palestinian families in Kubaniyat Im Haroun come under the provisions of the Protected Tenants Act 1972, the Israeli High Court has ruled that the Shamasneh family are not considered protected tenants and that their landlords are allowed to evict them.

The family recently received an eviction order from the execution office of Israel’s Enforcement and Collection Authority stating that the Shamasneh family must vacate its home by 9 August or face forcible eviction. On 14 August, the family’s lawyer requested a temporary restraining order to delay the eviction.

On 17 August 2017 at a hearing in the Jerusalem magistrate’s court, the Shamasneh family lawyer requested an injunction to delay the eviction on the grounds of the land registration procedures applied to the Shamasneh house. Different plot numbers were cited in the eviction order from those in the court ruling of 2013. The lawyer for the settlers claimed that the two numbers were the same building and was allowed to submit documents to this effect. At a subsequent hearing on 21 August, the judge rejected the Shamasneh’s request for an order to temporarily delay the eviction. The family lawyer is requesting permission to lodge an appeal against the magistrate’s court’s ruling. However, on 5 September, the family was evicted and the house was handed over to Israeli settlers.

From January to August, the Israeli authorities demolished 111 structures in East Jerusalem due to the lack of building permits, which are nearly impossible to obtain. This has resulted in the displacement of 179 people, including 107 children, and otherwise affected another 471 people. The communities most heavily affected were Jabal Mukabbir, Beit Hanina, al Isawiya and Silwan which, combined, accounted for 75 per cent of demolition incidents documented this year and 70 per cent of all structures demolished.

East Jerusalem, accounted for a third of all demolitions (112 out of 321)[15] and a third of all people displaced (179 out of 499) in the West Bank since the beginning of 2017. Around 25 per cent of structures demolished in East Jerusalem in 2017 were inhabited, while agricultural or livelihood-related structures accounted for some 39 per cent of all demolitions (See chart). The average number of people displaced in 2017 as a result of demolitions in East Jerusalem has slightly increased compared with the monthly average in 2016 (22.3 vs 21.2). In East Jerusalem 35% of confiscated land has been dedicated to Israeli settlement use; only 13% of East Jerusalem is zoned for Palestinian construction, much of which is already built-up. At least a third of all Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem lack Israeli-issued building permits, which are difficult to obtain, potentially placing over 100,000 residents at risk of displacement.

Coercive environment

Endnotes

[8] UNOCHA. East Jerusalem: Palestinians at Threat of Eviction. November 2016.

[9] ‘Netanyahu backs major expansion of Jerusalem to include nearby settlements, Times of Israel, 27 July 2017.

[10] See OCHA, Chapter 3, Settlement in East Jerusalem: Key Humanitarian Concerns, March 2011.

[11] ‘The Amana House: A New Settlement in Sheikh Jarrah’, Peace Now, 4 May 2016.

[12] See OCHA, The Case of Sheikh Jarrah: Updated Version, October 2010.

[13] See 2017 Humanitarian Needs Overview for the occupied Palestinian territory

[14] The Custodian General is the legal entity that serves as a trustee of any property in East Jerusalem which, prior to Israel’s occupation and annexation of the area in 1967, was held by the Jordanian Custodian of Enemy Property.

[15] This includes 111 structures demolished due to lack of building permits in addition to a structures demolished on punitive grounds.