Infestation expected to affect olive harvest in the West Bank

The 2018 olive harvest season will last approximately from mid-September to mid-November. However, a pest that infects olive trees, particularly in the norther West Bank, is expected to significantly reduce this year’s yield compared with 2017 (see box). In recent years, the olive harvest has also been affected negatively by Israeli settlers stealing or damaging olive trees, and by restrictions on access by Palestinian farmers to olive groves behind the Barrier and near Israeli settlements.

The annual olive harvest is a key economic, social and cultural event for Palestinians. More than 10 million olive trees are cultivated on approximately 86,000 hectares of land, representing 47 per cent of the total cultivated agricultural area. Olive and olive oil production is concentrated in the north and northwest of the West Bank. Between 80,000 and 100,000 families are said to rely on olives and olive oil for primary or secondary sources of income, and the sector employs large numbers of unskilled labourers and more than 15 per cent of working women. The entire olive sub-sector, including olive oil, table olives, pickles and soap, is worth between $160 and $191 million in good years.[1]

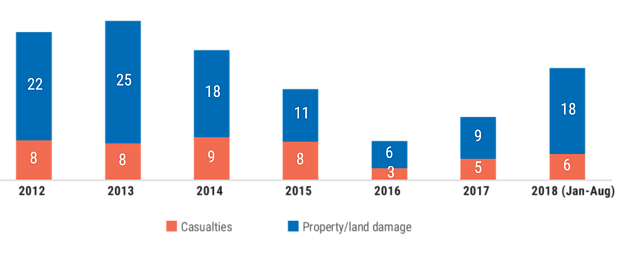

Monthly average of Israeli-settler related incidents resulting in Palestinian casualties or property damage

The 2017 yield was projected to be 19,000-20,000 MT (metric tons) of oil – higher than the 16,000 MT in 2016 but lower than the 21,000 MT in 2015 and the 24,000 MT in 2014 – and worth between $114 million and $120 million.

Settler violence and vandalism

Olive-based livelihoods in many areas of the West Bank are undermined by Israeli settlers who uproot and vandalize olive trees, and by intimidation and the physical assaults on farmers during the harvest itself. After a decline in recent years, settler violence has risen again. In 2018, by the end of August, there had been 186 incidents that resulted in Palestinian casualties or damage to Palestinian property compared with 157 and 98 in all of 2017 and 2016, respectively.

Concerns persist about holding violent settlers to account. The Israeli organization Yesh Din has monitored over 1,200 investigations opened by Israeli police into ideologically motivated crimes against Palestinians in the West Bank between 2005 and the end of 2017 following complaints filed by Palestinian victims. Only eight per cent of these investigations have led to indictments and only three per cent have resulted in a conviction. [2]

To address these and other protection concerns, the Protection Cluster, chaired by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, has coordinated the deployment of a protective presence to support Palestinian farmers and their families during the olive harvest over the past six years. Last year, PC members identified 70 locations across the West Bank most affected or at risk of settler violence and coordinated coverage of these locations by 19 organizations.

Restrictions on access to Palestinian land near settlements

The presence of settlements restricts access to Palestinian land for cultivation purposes. Approximately 90 Palestinian communities own land within or in the vicinity of 56 Israeli settlements and settlement outposts. In many cases, farmers can only access their land by means of ‘prior coordination’ with the Israeli authorities whereby access is generally permitted for a limited number of days during the harvest and ploughing seasons. As in previous years, many Palestinian farmers noted that the period of time allocated for the 2017 harvest was insufficient, that the Israeli army did not arrive at the designated time, or that part of their harvest or trees had been damaged by Israeli settlers during the period when farmers’ access to their own land was prohibited.

Permit requirements

Palestinian farmers require special permits or prior coordination to access farming land designated as ‘closed’ between the Barrier and the Green Line. If granted approval, farmers have to cross designated Barrier gates or checkpoints to reach the closed area. As documented by OCHA during the 2017 olive harvest, 76 gates were designated for agricultural access.[3] Of these, 54 only opened during the few weeks of the olive harvest, and only for a limited period of time on those days, and remained closed the rest of the year. An additional 10 gates are considered ‘weekly’ in that they open for some day(s) of the week throughout the year in addition to the olive season. Only 12 gates along the completed 465 kilometres of the Barrier open daily. Of the 76 gates, 56 require access permits and 20 operate via prior coordination.

To apply or renew a permit, the applicant must satisfy the security considerations necessary for all Israeli-issued permits. Many farmers are rejected on those grounds without further explanation. Applicants must also prove a connection to the land in the closed area by submitting valid ownership or land taxation documents. Some applicants are rejected on the grounds of ‘no connection to the land’ or ‘not having enough land.’ In the West Bank, the majority of land is not formally registered and ownership is passed over generations by traditional methods that do not require formal inheritance documentation. The land still constitutes a major source of income for successive generations.

OCHA monitors permit applications, particularly during the annual olive harvest when, according to the Israeli authorities, “recognizing the uniqueness and significance of the olive harvest season, agricultural employment permits beyond the set quota can be requested for members of the farmer’s family.” [4] In the northern West Bank (Jenin, Tulkarm, Qalqiliya and Salfit governorates) where the majority of Barrier gates (47) and the only crossings which open on a daily basis are located, the approval rate for permit applications declined slightly from 58 per cent in 2016 to 55 per cent for the 2017 olive harvest, in which a total of 12,582 permits were granted. Over 10,700 applications by farmers had been rejected or were still pending by the end of the olive harvest.

Impact of access restrictions on olive productivity

Access restrictions to land behind the Barrier and in the vicinity of settlements impede essential year-round agricultural activities such as ploughing, pruning, fertilizing, and pest and weed management. As a result, there is an adverse impact on olive productivity and value. Data collected by OCHA over the last four years in the northern West Bank show that the yield of olive trees in the area between the Barrier and the Green Line has reduced by approximately 55-65 per cent in comparison with equivalent trees in areas accessible all year round.

Olive production at risk

According to the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA), olive trees have been infected by an insect, the olive leaf gall midge, particularly in Tulkarem and Qalqiliya governorates in the northern West Bank. Based on initial estimates, the forthcoming olive harvest may be seriously affected with 80 per cent of production at risk. The MoA has requested NIS two million for surveillance and the study of the biology, behaviour, population density and infestation of the insect in close coordination with Palestinian universities and scientific research agencies. This money will also be used to distribute traps to prevent the uncontrolled spread of the insects. The MoA’s main objective is to prevent the insect from spreading to other areas of the West Bank through a rapid plan of action that does not include the use of pesticides due to the negative effects on the environment and to the insect’s natural enemies.

[1] PALTRADE, The State of Palestine National Export Strategy: Olive Oil, Sector Export Strategy 2014-2018, pp. 5-9. In a typical year, approximately 75 per cent of olive oil is absorbed by the domestic market, 14 per cent is exported to Arab markets and eight per cent is exported to Israel.

[2] Yesh Din data sheet: Law enforcement on Israeli civilians in the West Bank, December 2017.

[3] This figure excludes Barrier checkpoints not used to access agricultural land but by residents of the “Seam Zone” to reach workplaces and essential services in the rest of the West Bank.

[4] Unofficial translation from fifth edition of the ‘Standing Orders’ published by the Israeli authorities, which detail the regulations governing access to areas behind the Barrier.